Henrietta Louisa Koenen was born a century before the Guerrilla Girls, but her collecting habits are a strong argument for honorary, posthumous membership in the activist group.

The wife of the Rijksmuseum’s Print Room’s first director, Koenen spent over three decades acquiring prints by female artists, though discouragingly few of the 827 women in her collection achieved much in the way of recognition for their work.

Renaissance aristocratic painter, Sofonisba Anguissola, and portraitist (and founding member of London’s Royal Academy of Arts) Angelica Kauffman, have the distinction of being namechecked in the Guerrilla Girl’s 1989 provocation, below.

Neither can be said to enjoy the museum tote bag celebrity of a Kahlo or O’Keeffe.

Self portait, Angelica Kauffman

Their work can be expected to attract some new fans, now that 80 some pieces from Koenen’s collection are on display as part of the New York Public Library’s exhibit, Printing Women: Three Centuries of Female Printmakers, 1570–1900.

(And it would be unseemly not to credit American art dealer Samuel Putnam Avery, for donating Koenen’s collection to the library at the turn of the last century, twenty years after her death.)

Printmaking is a frequently collaborative art. The droll Young Girl Laughing at the Old Woman, above, was drawn by Anguissola and engraved by Jacob Bos.

And Maria Cosway’s Music Has Charms, at the top of this post, was a family affair, with Cosway printing husband Richard’s celestial rendering of daughter Louisa Paolina Angelica. (Mrs. Cosway was also an accomplished composer and painter of miniatures and mythological scenes, though history has decreed her most enduring claim to fame should be her hold over a besotted Thomas Jefferson.)

The library highlights the continuum with an online gallery showcasing the work of contemporary female printmakers, some of whom are contributing guest posts to curator Madeleine Viljoen’s Printing Women blog.

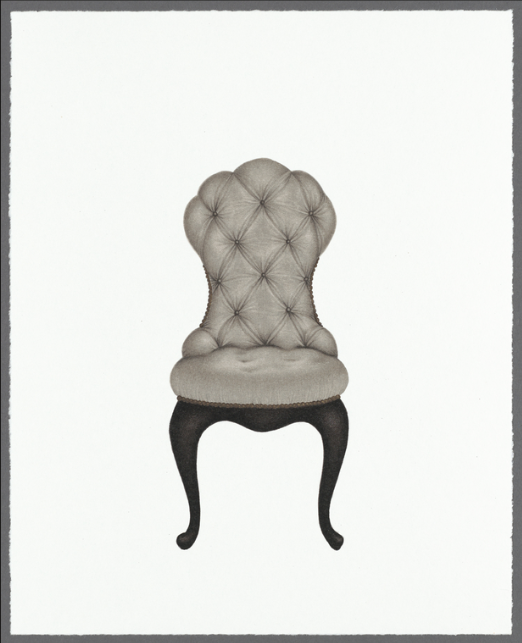

Sara Sanders, whose 2010 Lithograph, Untitled Chair #5, above, is part of a larger series, writes:

I believe that the domestic objects with which we spend our lives retain traces of our histories and tell stories about our pasts. These prints are part of an ongoing series of portraits of chairs drawn in the way we imagine them to be. Two of the chairs in this series were drawn from existing objects with a rich history, while the rest are imagined character studies.

Her thoughts seem particularly germane, when the “lesser genres” of ornament, still-life, and landscape were by default frequent subjects for the female artists in Koenen’s collection. Propriety deemed the fairer sex should not be party to the nude figure studies that significant religious and historical scenes so often demanded.

(Channel your inner Guerrilla Girl by performing an image search on Rape of the Sabine Women, and imagining the models as aspirant artists themselves, confined to such subject matter as violets and laundry day.)

That’s not to say domestic subjects can’t prove divine.

Witness 1751’s A Child Seated, Blowing Bubbles by Madame de Pompadour, an amateur artist and frequently painted beauty, who, the National Gallery’s website informs us, was “groomed from childhood to become a plaything for the King.”

View the online brochure for New York Public Library’s Printing Women: Three Centuries of Female Printmakers, 1570–1900 exhibition here. The exhibition at The New York Public Library ends May 27th, 2016.

Related Content:

11 Essential Feminist Books: A New Reading List by The New York Public Library

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Leave a Reply