Frequently, I see stories in the education news reporting on a textbook company, school board, or curriculum attempting to minimize or erase the history of slavery in the United States. One recent example made national news: a textbook published by McGraw-Hill that described the Atlantic slave trade as bringing “millions of workers from Africa to the United States to work on agricultural plantations.”

Roni Dean-Burren—mother of the student who noticed the “error” and herself an educator—pointed out, writes NPR, that “while the book describes many Europeans immigrating as indentured servants,” there was “no mention in this lesson of Africans forced to the U.S. as slaves.” It’s pretty egregiously bad historical framing; describing slaves as migrant “workers” is at best gross understatement and at worst disinformation.

The textbook company maintains it was a mistake, others have alleged a deliberate whitewash of a history that makes many people uncomfortable. Similarly heated controversies have arisen around certain puzzlingly cheerful children’s books. I won’t weigh in here on the politics of these debates, but I am very curious about why teaching the history of slavery is such a contentious issue in classrooms across the country.

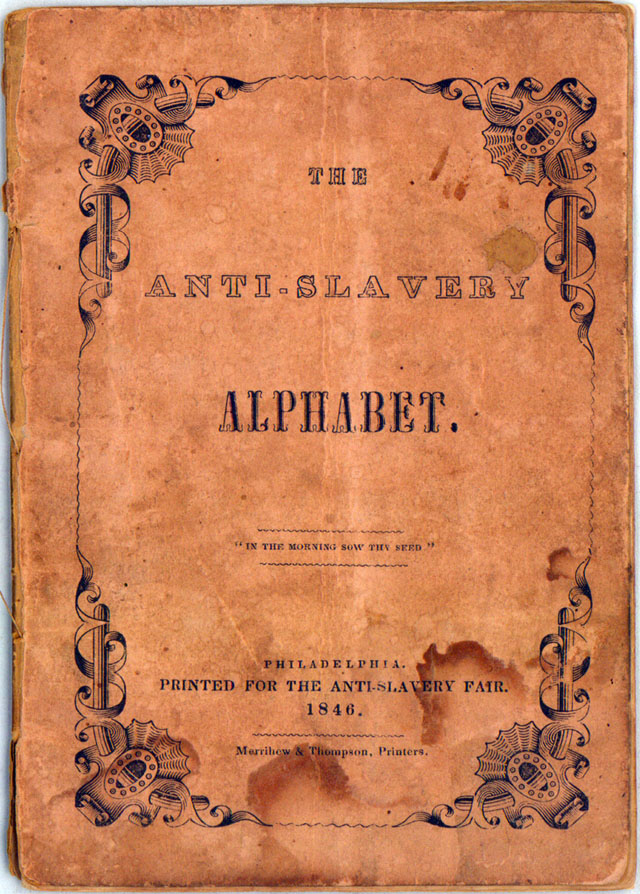

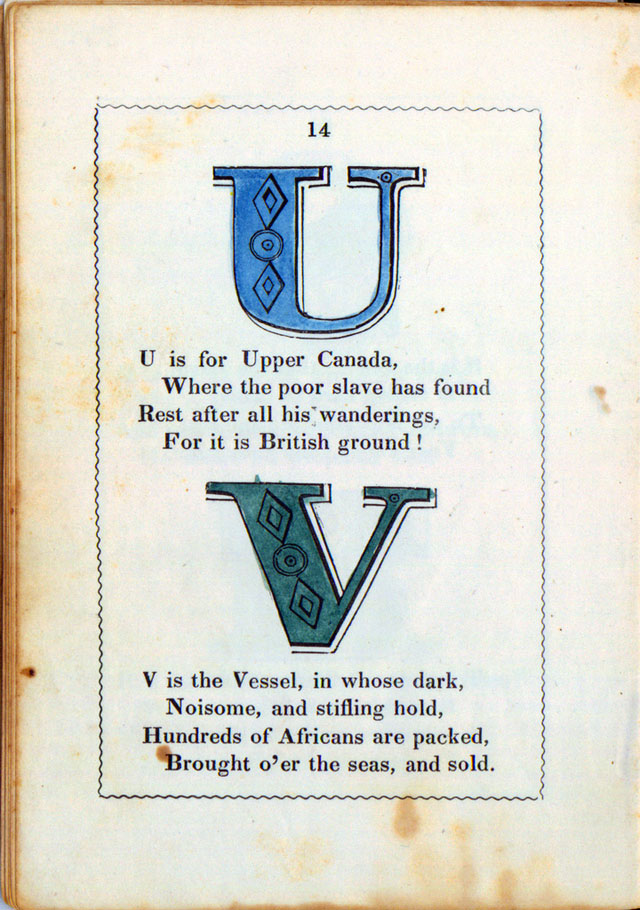

If you were to ask most teachers, they would—one hopes—denounce U.S. slavery as a great moral wrong and praise its end as self-evidently necessary. So what would it look like to teach the subject that way? Well, for one thing, teachers and parents might refer to primary documents like “The Anti-Slavery Alphabet,” an abolitionist teaching tool written by Quakers Hannah and Mary Townsend and sold at the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery society fair in 1846.

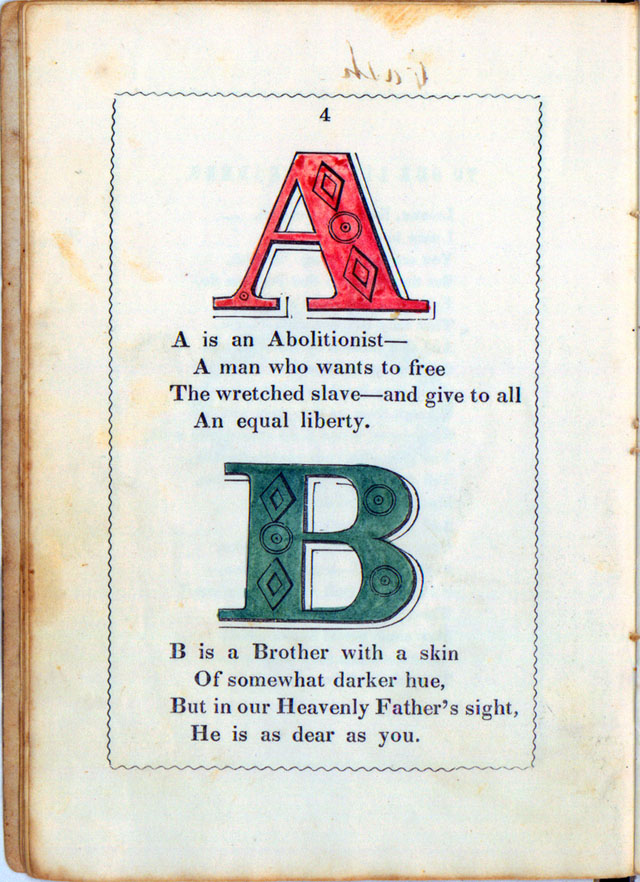

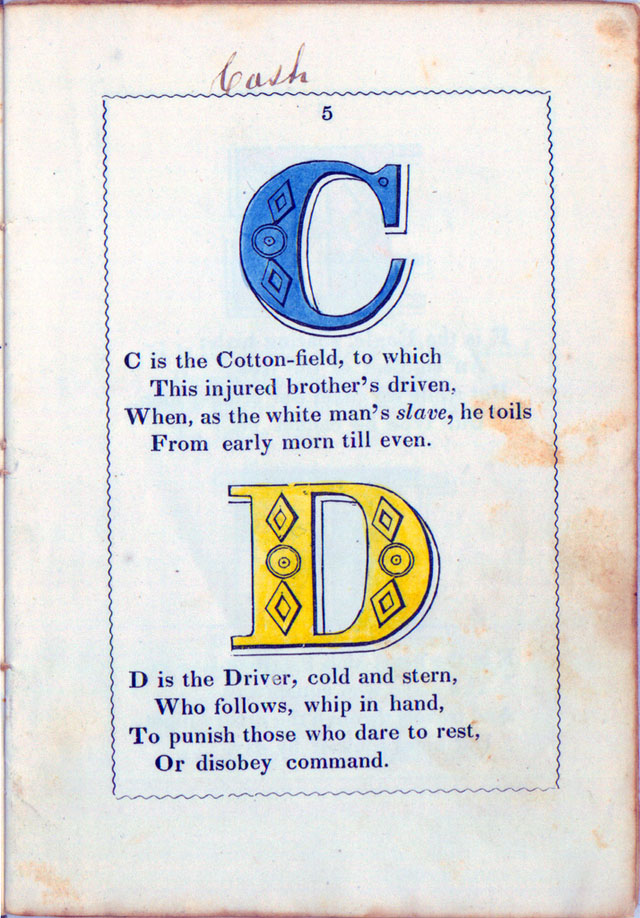

The alphabet, writes The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, “consists of sixteen leaves, printed on one side, with the printed pages facing each other and hand-sewn into a paper cover. Each of the letter illustrations is hand-colored.” Certainly a labor of love, and though targeted to young children, it is instructive for students of all ages to see how abolitionist pedagogy framed these issues, refusing to soft-pedal the “wretched” conditions slaves endured.

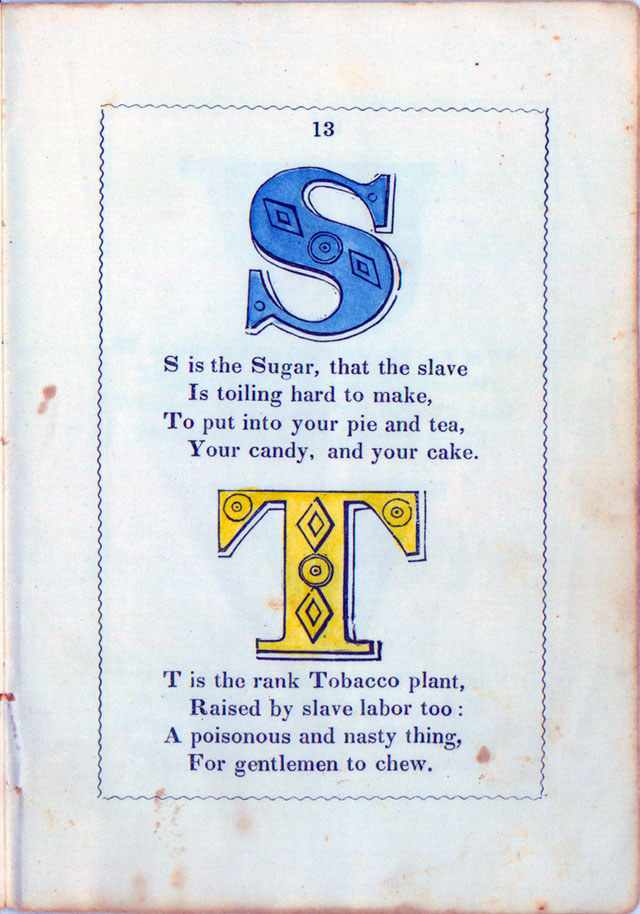

Nor does this text shy away from directly relating these conditions to the commodity market that sustained them. In the page below, for example, children learn that the sugar “put into your pie and tea / Your candy, and your cake,” comes from slave labor. Ditto the “poisonous and nasty” tobacco the gentlemen chew.

The language, as is typical of the time, is occasionally sentimental or sternly moralistic, but the facts do not suffer much for it. Is this propaganda? Certainly, for a point of view that would take another 20 years, a bloody civil war, and a long struggle through a failed Reconstruction and brutal Jim Crow era to take hold nationwide, pockets of reactionaries notwithstanding.

To see all of “The Anti-Slavery Alphabet,” visit The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit or the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, who allow you to zoom in and examine each page closely. For more contemporary books for children on the history of slavery, see this list of “13 Honest Books About Slavery.” And for a wealth of primary abolitionist documents from the late 18th to the late 19th ( as well as more recent texts on modern slavery) see the archive of “50 Essential Documents” at the Abolition Seminar, an “educational tool for teachers, students, and all who fight for freedom.

Related Content:

Visualizing Slavery: The Map Abraham Lincoln Spent Hours Studying During the Civil War

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

This is a gem. The history of the human rights movement in the U.S. is as vital as the history of oppression.

I found this little book in my mother’s house. Is there any value to it or some museum, etc that would like it?

It’s probably too late but I would love to have it.

I AM BY USA miseduction due every form of reparation payments missed and to become due. Reparation creditor Johnny lee Richmond 5261 nth 33rd Street milwaukee wisconsin 53209