It has long been thought that the so-called “Golden Ratio” described in Euclid’s Elements has “implications for numerous natural phenomena… from the leaf and seed arrangements of plants” and “from the arts to the stock market.” So writes astrophysicist Mario Livio, head of the science division for the institute that oversees the Hubble Telescope. And yet, though this mathematical proportion has been found in paintings by Leonardo da Vinci to Salvador Dali—two examples that are only “the tip of the iceberg in terms of the appearances of the Golden Ratio in the arts”—Livio concludes that it does not describe “some sort of universal standard for ‘beauty.’” Most art of “lasting value,” he argues, departs “from any formal canon for aesthetics.” We can consider Livio a Golden Ratio skeptic.

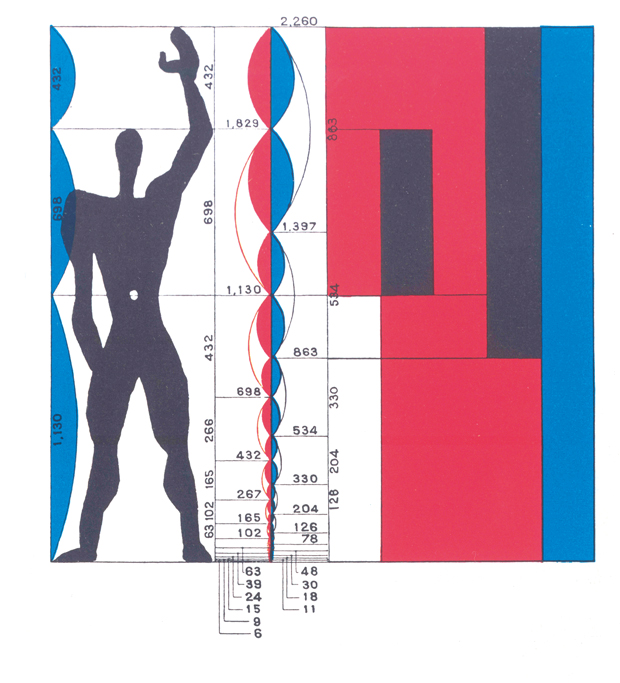

Far on the other end of a spectrum of belief in mathematical art lies Le Corbusier, Swiss architect and painter in whose modernist design some see an almost totalitarian mania for order. Using the Golden Ratio, Corbusier designed a system of aesthetic proportions called Modulor, its ambition, writes William Wiles at Icon, “to reconcile maths, the human form, architecture and beauty into a single system.”

Praised by Einstein and adopted by a few of Corbusier’s contemporaries, Modulor failed to catch on in part because “Corbusier wanted to patent the system and earn royalties from buildings using it.” In place of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, Corbusier proposed “Modulor Man” (below) the “mascot of [his] system for reordering the universe.”

Perhaps now, we need an artist to render a “Fractal Man”—or Fractal Gender Non-Specific Person—to represent the latest enthusiastic findings of math in the arts. This time, scientists have quantified beauty in language, a medium sometimes characterized as so imprecise, opaque, and unscientific that the Royal Society was founded with the motto “take no one’s word for it” and Ludwig Wittgenstein deflated philosophy with his conclusion in the Tractatus, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” (Speaking, in this sense, meant using language in a highly mathematical way.) Words—many scientists and philosophers have long believed—lie, and lead us away from the cold, hard truths of pure mathematics.

And yet, reports The Guardian, scientists at the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Poland have found that James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake—a novel we might think of as perhaps the most self-consciously referential examination of language written in any tongue—is “almost indistinguishable in its structure from a purely mathematical multifractal.” Trying to explain this finding in as plain English as possible, Julia Johanne Tolo at Electric Literature writes:

To determine whether the books had fractal structures, the academics looked at the variation of sentence lengths, finding that each sentence, or fragment, had a structure that resembled the whole of the book.

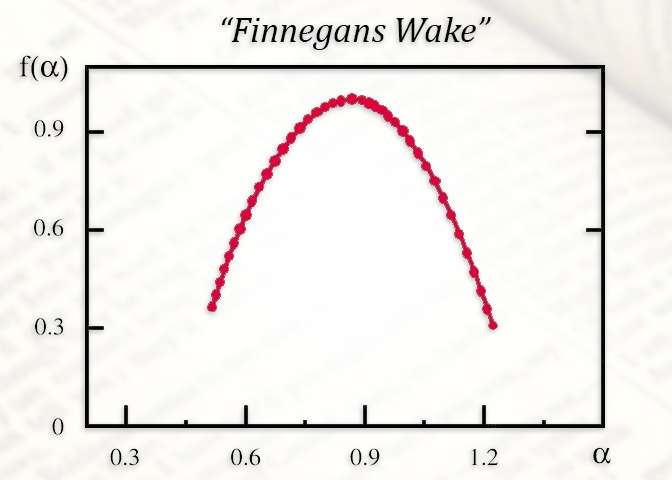

And it isn’t only Joyce. Through a statistical analysis of 113 works of literature, the researchers found that many texts written by the likes of Dickens, Shakespeare, Thomas Mann, Umberto Eco, and Samuel Beckett had multifractal structures. The most mathematically complex works were stream-of-consciousness narratives, hence the ultimate complexity of Finnegans Wake, which Professor Stanisław Drożdż, co-author of the paper published at Information Sciences, describes as “the absolute record in terms of multifractality.” (The graph at the top shows the results of the novel’s analysis, which produced a shape identical to pure mathematical multifractals.)

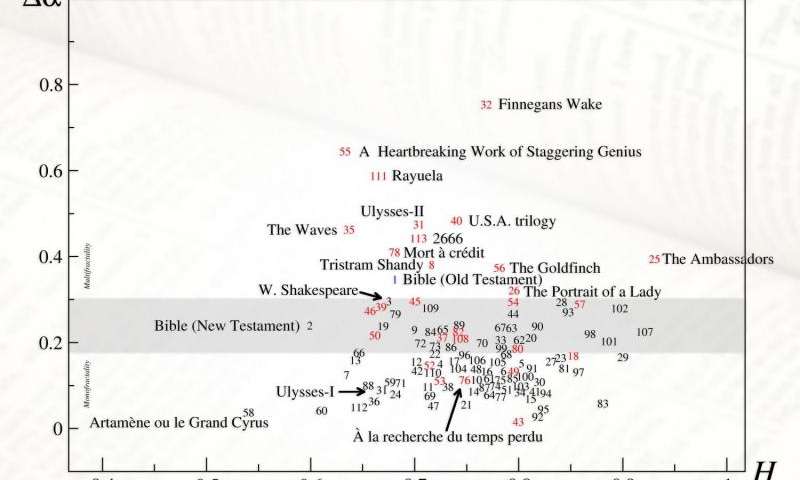

This study produced some inconsistencies, however. In the graph above, you can see how many of the titles surveyed ranked in terms of their “multifractality.” A close second to Joyce’s classic work, surprisingly, is Dave Egger’s post-modern memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, and much, much further down the scale, Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. Proust’s masterwork, writes Phys.org, shows “little correlation to multifractality” as do certain other books like Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. The measure may tell us little about literary quality, though Professor Drożdż suggests that “it may someday help in a more objective assignment of books to one genre or another.” Irish novelist Eimear McBride finds this “upshot” disappointing. “Surely there are more interesting questions about the how and why of writers’ brains arriving at these complex, but seemingly instinctive, fractals?” she told The Guardian.

Of the finding that stream-of-consciousness works seem to be the most fractal, McBride says, “By its nature, such writing is concerned not only with the usual load-bearing aspects of language—content, meaning, aesthetics, etc—but engages with language as the object in itself, using the re-forming of its rules to give the reader a more prismatic understanding…. Given the long-established connection between beauty and symmetry, finding works of literature fractally quantifiable seems perfectly reasonable.” Maybe so, or perhaps the Polish scientists have fallen victim to a more sophisticated variety of the psychological sharpshooter’s fallacy that affects “Bible Code” enthusiasts? I imagine we’ll see some fractal skeptics emerge soon enough. But the idea that the worlds-within-worlds feeling one gets when reading certain books—the sense that they contain universes in miniature—may be mathematically verifiable sends a little chill up my spine.

Related Content:

Hear All of Finnegans Wake Read Aloud: A 35 Hour Reading

See What Happens When You Run Finnegans Wake Through a Spell Checker

James Joyce Reads From Ulysses and Finnegans Wake In His Only Two Recordings (1924/1929)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Well, here’s a fractal skeptic. It’s possible to find all kinds of patterns in a literary text that mean, perhaps, nothing. Jonathan Culler’s discussion of the patterns found by Roman Jakobson in (I think) Baudelaire’s poetry is relevant here.

But also: stream of consciousness is a way of representing a character’s thought processes. (Distinguished, too, from interior monologue.) It’s hard to call Finnegans Wake a stream-of-consciousness novel. Ulysses has many passages of stream of consciousness but much else besides. Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is not an example of s‑o-c writing.

You had me at Dave Eggers.

Proust’s novel was one of the novels they said did not have a fractal nature to it. So I don’t think the post meant to describe it as one.

That’s interesting … but … The plain-English (nonfractal?) explanation of the measuring process seems a little vague to me — though I could certainly just not be “getting it.” (I didn’t click through any of the links.) A sentence is the only type of fragment measured, is that what it says? I’m having trouble understanding how all sentences in their variety (“each sentence”) can then resemble the whole book … unless they are starting to count letters per word?? In any case, while this degree-of-fractalness could reflect somw writing-style decisions, it seems to me it is probably more likely to be random in most cases; is that a principal feature of fractals? Multifractals? I wonder: Have they got stats on the number of lit-fractals per genre — macro (non-fiction/fiction) and micro (novel/comic book, etc.)? And do those stats resemble a fractal? (Finally, is a parabola a type of fractal?) [Really finally, how does this comment score/graph?]

Maybe we can call it automatic writing, as in surrealism and psycanalisis

d block wrote: “Proust’s novel was one of the novels they said did not have a fractal nature to it. So I don’t think the post meant to describe it as one.”

No, the post didn’t. But the Phys.org page describes it as s‑o-c: “At the same time, a lot of works usually regarded as stream of consciousness turned out to show little correlation to multifractality, as it was hardly noticeable in books such as Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand and A la recherche du temps perdu by Marcel Proust.”

Captivated by this thesis and the follow-up Qs and push-backs, here and also at the original guardian publication site. Curious to know where Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. would fall on the graph (see “Passing through the Equal Sign” in book edited by Andrew Horton), or on its analog for works of film.

…Not to mention Film, Keaton’s offbeat experiment w/ Beckett.

Someone needs to really dumb this article down for me–I’m really struggling to get this. What exactly is fractal about these pieces of writing? The only thing I got from the article was “sentence length.” Are they saying the fluctuations in sentence length are what make up this fractal shape?

My head hurts now, shouldn’t have read this post twice. String Theory is way easier to understand. I’ll try again tomorrow.

Some Bach pieces show fractal traits in ways that are much more interesting than sentence length- for example, fugues where the melody predicts what keys the piece will modulate through.