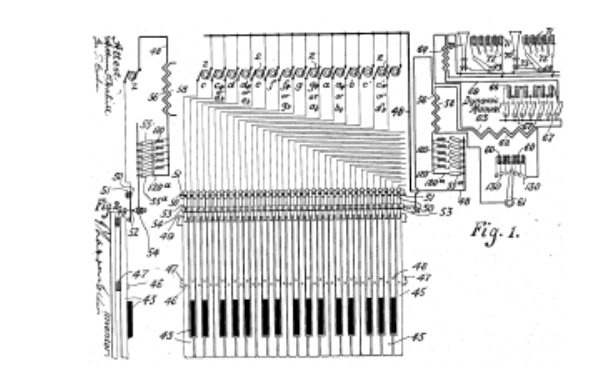

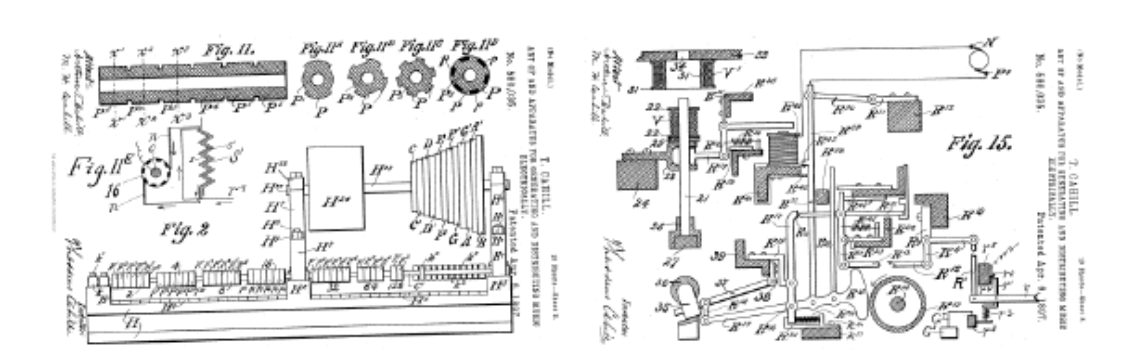

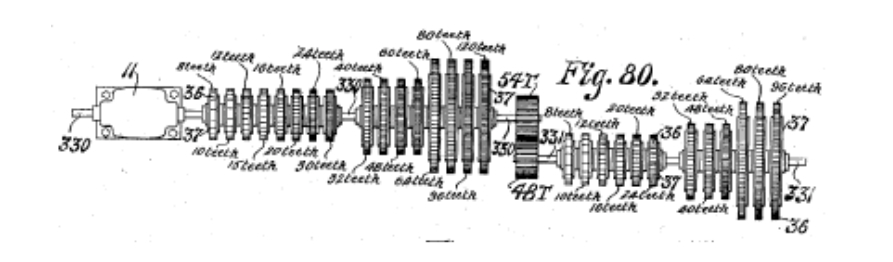

Before the New Year, we brought you footage of Russian polymathic inventor Léon Theremin demonstrating the strange instrument that bears his surname, and we noted that the Theremin was the first electronic instrument. This is not strictly true, though it is the first electronic instrument to be mass produced and widely used in original composition and performance. But like biological evolution, the history of musical instrument development is littered with dead ends, anomalies, and forgotten ancestors (such as the octobass). One such obscure oddity, the Telharmonium, appeared almost 20 years before the Theremin, and it was patented by its American inventor, Thaddeus Cahill, even earlier, in 1897. (See some of the many diagrams from the original patent below.)

Cahill, a lawyer who had previously invented devices for pianos and typewriters, created the Telharmonium—also called the Dynamaphone—to broadcast music over the telephone, making it a precursor not to the Theremin but to the later scourge of telephone hold music. “In a large way,” writes Jay Williston at Synthmuseum.com, “Cahill invented what we know of today as ‘Muzak.’” He built the first prototype Telharmonium, the Mark I, in 1901. It weighed seven tons. The final incarnation of the instrument, the Mark III, took 50 people to build at the cost of $200,000 and was “60 feet long, weighed almost 200 tons and incorporated over 2000 electric switches…. Music was usually played by two people (4 hands) and consisted of mostly classical works by Bach, Chopin, Greig, Rossini and others.” The workings of the gargantuan machine resemble the boiler room of an industrial facility. (See several photographs here.)

Needless to say, this was a highly impractical instrument. Nevertheless, Cahill not only found willing investors for the enormous contraption, but he also staged successful demonstrations in Baltimore, then—after disassembling and moving the thing by train—in New York. By 1905, his New England Electric Music Company “made a deal with the New York Telephone Company to lay special lines so that he could transmit the signals from the Telharmonium throughout the city.” Cahill used the term “synthesizing” in his patent, which some say makes the Telharmonium the first synthesizer, though its operation was as much mechanical as electronic, using a complicated series of gears and cylinders to replicate the musical range of a piano. (See the operation explained in the video at the top.) “Raised bumps on cylinders helped create musical contour notes,” writes Popular Mechanics, “not unlike a music box, with the size of the cylinder determining the pitch.”

The huge, very loud Telharmonium Mark III ended up in the basement of the Metropolitan Opera House for a time as Cahill worked on his scheme for pumping music through the telephone lines. But this plan did not come off smoothly. “The problem was,” Popular Mechanics points out,” all cables leak off radio waves. Sending a gigantic, amplified signal on turn-of-the-20th-century phone lines was bound to cause trouble.” The Telharmonium created interference on other phone lines and even interrupted Naval radio transmissions. “Rumor has it,” the Douglas Anderson School of the Arts writes, “that a New York businessman, infuriated by the constant network interference, broke into the building where the Telharmonium was housed and destroyed it, throwing pieces of the machinery into the Hudson river below.”

The story seems unlikely, but it serves as a symbol for the instrument’s collapse. Cahill’s company folded in 1908, though the final Telharmonium supposedly remained operational until 1916. No recordings of the instrument have survived, and Thaddeus Cahill’s brother Arthur eventually sold the last prototype off for scrap in 1950 after failing to find a buyer. The entire rationale for the instrument had been supplanted by radio broadcasting. The Telharmonium may have failed to catch on, but it still had a significant impact. Its unique design inspired another important electronic instrument, the Hammond organ. And its very existence gave musical futurists a vision. The Douglas Anderson School writes:

Despite its final demise, the Telharmonium triggered the birth of electronic music—The Italian Composer and intellectual Ferruccio Busoni inspired by the machine at the height of its popularity was moved to write his “Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music” (1907) which in turn became the clarion call and inspiration for the new generation of electronic composers such as Edgard Varèse and Luigi Russolo.

The instrument also made quite an impression on another American inventor, Mark Twain, who enthusiastically demonstrated it through the telephone during a New Year’s gathering at his home, after giving a speech about his own not inconsiderable status as an innovator and early adopter of new technologies. “Unfortunately for Thaddeus Cahill,” writes William Weir at The Hartford Courant, “Twain’s support wasn’t enough to make a success of the Telharmonium.” Learn more about the instrument’s history from this book.

Related Content:

Thomas Dolby Explains How a Synthesizer Works on a Jim Henson Kids Show (1989)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Any idea how many subscribers he ended up having and what the rate of subscription was like?