The end of 2015 has been dominated by crises. At times, amidst the daily barrage of fearful spectacle, it can be difficult to conceive of the years around the corner in ways that don’t resemble the next crop of blow-em-up action movies, nearly every one of which depicts some variation on the seemingly inexhaustible theme of the end-of-the-world. There’s no doubt many of our current challenges are unprecedented, but in the midst of anxieties of all kinds it’s worth remembering that—as Steven Pinker has thoroughly demonstrated—“violence has declined by dramatic degrees all over the world.”

In other words, as bad as things can seem, they were much worse for most of human history. It’s a long view cultural historian Otto Friedrich took in a grim survey called The End of the World: A History. Written near the end of the Cold War, Friedrich’s book documents some 2000 years of European catastrophe, during which one generation after another genuinely believed the end was nigh. And yet, certain far-seeing individuals have always imagined a thriving human future, especially during the profoundly destructive 20th century.

In 1900, engineer John Elfreth Watkins made a survey of the scientific minds of his day. As we noted in a previous post, some of those predictions of the year 2000 seem prescient, some preposterous; all boldly extrapolated contemporary trends and foresaw a radically different human world. At the height of the Cold War in 1964, Isaac Asimov partly described our present in his 50 year forecast. In 1926, and again 1935, no less a visionary than Nikola Tesla looked into the 21st century to envision a world both like and unlike our own.

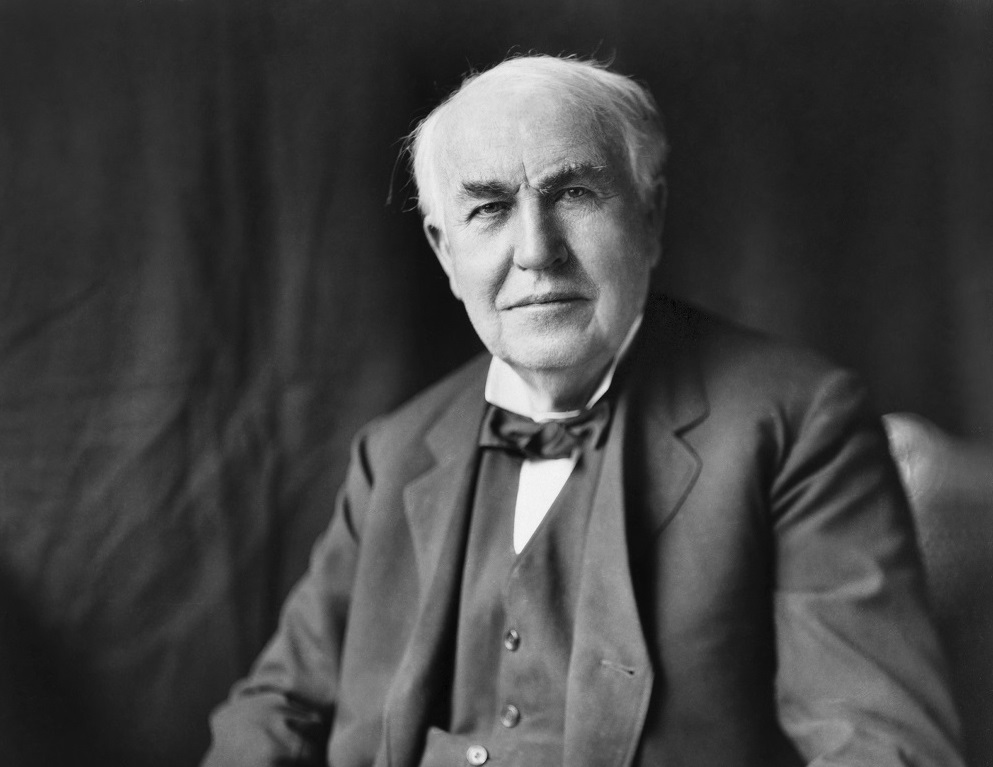

Several years earlier in 1911, Tesla’s rival Thomas Edison made his own set of futuristic predictions for 100 years hence in a Cosmopolitan article. These were also summarized in an article published that year by the Miami Metropolis, which begins by lauding Edison as a “wizard… who has wrested so many secrets from jealous Nature.” We’ve condensed Edison’s predictions in list form below. Compare these to Tesla’s visions for a fascinating contrast of two different, yet complementary future worlds.

1. Steam power, already on the wane, will rapidly disappear: “In the year 2011 such railway trains as survive will be driven at incredible speed by electricity (which will also be the motive force of all the world’s machinery).”

2. “[T]he traveler of the future… will fly through the air, swifter than any swallow, at a speed of two hundred miles an hour, in colossal machines, which will enable him to breakfast in London, transact business in Paris and eat his luncheon in Cheapside.”

3. “The house of the next century will be furnished from basement to attic with steel… a steel so light that it will be as easy to move a sideboard as it is today to lift a drawing room chair. The baby of the twenty-first century will be rocked in a steel cradle; his father will sit in a steel chair at a steel dining table, and his mother’s boudoir will be sumptuously equipped with steel furnishings….”

4. Edison also predicted that steel reinforced concrete would replace bricks: “A reinforced concrete building will stand practically forever.” By 1941, he told Cosmopolitan, “all constructions will be of reinforced concrete, from the finest mansions to the tallest skyscrapers.”

5. Like many futurists of the previous century, and some few today, Edison foresaw a world where tech would eradicate poverty: “Poverty was for a world that used only its hands,” he said; “Now that men have begun to use their brains, poverty is decreasing…. [T]here will be no poverty in the world a hundred years from now.”

6. Anticipating agribusiness, Edison predicted, “the coming farmer will be a man on a seat beside a push-button and some levers.” Farming would experience a “great shake-up” as science, tech, and big business overtook its methods.

7. “Books of the coming century will all be printed leaves of nickel, so light to hold that the reader can enjoy a small library in a single volume. A book two inches thick will contain forty thousand pages, the equivalent of a hundred volumes.”

8. Machines, Edison told Cosmopolitan, “will make the parts of things and put them together, instead of merely making the parts of things for human hands to put together. The day of the seamstress, wearily running her seam, is almost ended.”

9. Telephones, Edison confidently predicted, “will shout out proper names, or whisper the quotations from the drug market.”

10. Anticipating the logic of the Cold War arms race, though underestimating the mass destruction to precede it, Edison believed the “piling up of armaments” would “bring universal revolution or universal peace before there can be more than one great war.”

11. Edison “sounds the death knell of gold as a precious metal. ‘Gold,’ he says, ‘has even now but a few years to live. They day is near when bars of it will be as common and as cheap as bars of iron or blocks of steel.’”

He then went on, astonishingly, to echo the pre-scientific alchemists of several hundred years earlier: “’We are already on the verge of discovering the secret of transmuting metals, which are all substantially the same matter, though combined in different proportions.’”

Excited by the future abundance of gold, the Miami Metropolis piece on Edison’s predictions breathlessly concludes, “In the magical days to come there is no reason why our great liners should not be of solid gold from stem to stern; why we should not ride in golden taxicabs, or substituted gold for steel in our drawing rooms.”

In reading over the predictions from shrewd thinkers of the past, one is struck as much by what they got right as by what they got often terribly wrong. (Matt Novak’s Paleofuture, which brings us the Miami Metropolis article, has chronicled the checkered, hit-and-miss history of futurism for several years now.) Edison’s tone is more strident than most of his peers, but his accuracy was about on par, further suggesting that neither the most confident of techno-futurists, nor the most baleful of doomsayers knows quite what the future holds: their clearest forecasts obscured by the biases, technical limitations, and philosophical categories of their present.

via Paleofuture

Related Content:

In 1964, Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Internet, 3D Printers and Trained Monkey Servants

In 1704, Isaac Newton Predicts the World Will End in 2060

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Most of what Steven Pinker says is pointless. Despite the total proportion of violence going down, on an absolute scale it has risen, especially in recent years. And even if violence had remained static, information availability has risen dramatically, making it appear as if there is more violence compared to earlier years.