Image by The USO, via Flickr Commons

Though few of us like to hear it, the fact remains that success in any endeavor requires patient, regular training and a daily routine. To take a mundane, well-worn example, it’s not for nothing that Stephen R. Covey’s best-selling classic of the business and self-help worlds offers us “7 Habits of Highly Effective People,” rather than “7 Sudden Breakthroughs that Will Change Your Life Forever”—though if we credit the spam emails, ads, and sponsored links that clutter our online lives, we may end up believing in quick fixes and easy roads to fame and fortune. But no, a well-developed skill comes only from a set of practiced routines.

That said, the type of routine one adheres to depends on very personal circumstances such that no single creative person’s habits need exactly resemble any other’s. When it comes to the lives of writers, we expect some commonality: a writing space free of distractions, some preferred method of transcription from brain to page, some set time of day or night at which the words flow best. Outside of these basic parameters, the daily lives of writers can look as different as the images in their heads.

But it seems that once a writer settles on a set of habits—whatever they may be—they stick to them with particular rigor. The writing routine, says hyper-prolific Stephen King, is “not any different than a bedtime routine. Do you go to bed a different way every night?” Likely not. As for why we all have our very specific, personal quirks at bedtime, or at writing time, King answers honestly, “I don’t know.”

So what does King’s routine look like? “There are certain things I do if I sit down to write,” he’s quoted as saying in Lisa Rogak’s Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King:

“I have a glass of water or a cup of tea. There’s a certain time I sit down, from 8:00 to 8:30, somewhere within that half hour every morning,” he explained. “I have my vitamin pill and my music, sit in the same seat, and the papers are all arranged in the same places. The cumulative purpose of doing these things the same way every day seems to be a way of saying to the mind, you’re going to be dreaming soon.”

The King quotes come to us via the site (and now book) Daily Routines, which features brief summaries of “how writers, artists, and other interesting people organize their days.” We’ve previously featured a few snapshots of the daily lives of famous philosophers. The writers section of the site similarly offers windows into the daily practices of a wide range of authors, from the living to the long dead.

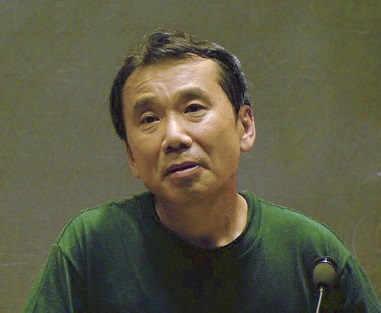

Image via Wikimedia Commons

A contemporary of King, though a slower, more self-consciously painstaking writer, Haruki Murakami incorporates into his workday his passion for running, an avocation he has made central to his writing philosophy. Expectedly, Murakami keeps a very athletic writing schedule and routine.

When I’m in writing mode for a novel, I get up at 4:00 am and work for five to six hours. In the afternoon, I run for 10km or swim for 1500m (or do both), then I read a bit and listen to some music. I go to bed at 9:00 pm. I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind. But to hold to such repetition for so long — six months to a year — requires a good amount of mental and physical strength. In that sense, writing a long novel is like survival training. Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.

Not all writers can adhere to such a disciplined way of living and working, particularly those whose waking hours are given over to other, usually painfully unfulfilling, day jobs.

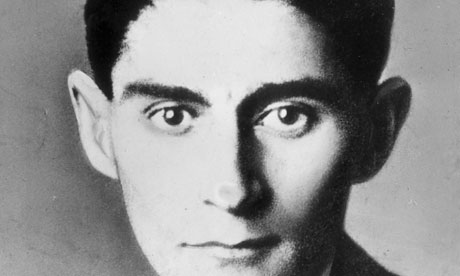

Image of Franz Kafka, via Wikimedia Commons

An almost archetypal case of the writer trapped in such a situation, Franz Kafka kept a routine that would cripple most people and that did not bring about physical strength, to say the least. As Zadie Smith writes of the author’s portrayal in Louis Begley’s biography, Kafka “despaired of his twelve hour shifts that left no time for writing.”

[T]wo years later, promoted to the position of chief clerk at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, he was now on the one-shift system, 8:30 AM until 2:30 PM. And then what? Lunch until 3:30, then sleep until 7:30, then exercises, then a family dinner. After which he started work around 11 PM (as Begley points out, the letter- and diary-writing took up at least an hour a day, and more usually two), and then “depending on my strength, inclination, and luck, until one, two, or three o’clock, once even till six in the morning.” Then “every imaginable effort to go to sleep,” as he fitfully rested before leaving to go to the office once more. This routine left him permanently on the verge of collapse.

Might he have chosen a healthier way? When his fiancée Felice Bauer suggested as much, Kafka replied, “The present way is the only possible one; if I can’t bear it, so much the worse; but I will bear it somehow.” And so he did, until his early death from tuberculosis.

While writers require routine, nowhere is it written that their habits must be salubrious or measured. According to Simone De Beauvoir, outré French writer Jean Genet “puts in about twelve hours a day for six months when he’s working on something and when he has finished he can let six months go by without doing anything.” Then there are those writers who have relied on pointedly unhealthy, even dangerous habits to propel them through their workday. Not only did William S. Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson write under the influence, but so also did such a seemingly conservative person as W.H. Auden, who “swallowed Benzedrine every morning for twenty years… balancing its effect with the barbiturate Seconal when he wanted to sleep.” Auden called the amphetamine habit a “labor saving device” in the “mental kitchen,” though he added that “these mechanisms are very crude, liable to injure the cook, and constantly breaking down.”

So, there you have it, a very diverse sampling of routines and habits in several successful writers’ lives. Though you may try to emulate these if you harbor literary ambitions, you’re probably better off coming up with your own, suited to the oddities of your personal makeup and your tolerance—or not—for serious physical exercise or mind-altering substances. Visit Daily Routines to learn about many more famous writers’ habits.

Related Content:

The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People, Presented in an Interactive Infographic

Haruki Murakami Lists the Three Essential Qualities For All Serious Novelists (And Runners)

Stephen King’s Top 20 Rules for Writers

The Daily Habits of Highly Productive Philosophers: Nietzsche, Marx & Immanuel Kant

Philosophers Drinking Coffee: The Excessive Habits of Kant, Voltaire & Kierkegaard

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A very diverse sampling that discusses ONLY the habits of male writers? Wow. Two major female writers are quoted here, talking about the habits of male writers.

Say what you will about the brutality they put themselves through, you have to admire their commitment to their art.

Megan! Just for you. Here is Maya Angelou’s writing routine via James Clear’s blog via an interview with The Daily Beast. His website has some more male and female routines. http://jamesclear.com/daily-routines-writers

“I keep a hotel room in my hometown and pay for it by the month.

I go around 6:30 in the morning. I have a bedroom, with a bed, a table, and a bath. I have Roget’s Thesaurus, a dictionary, and the Bible. Usually a deck of cards and some crossword puzzles. Something to occupy my little mind. I think my grandmother taught me that. She didn’t mean to, but she used to talk about her “little mind.” So when I was young, from the time I was about 3 until 13, I decided that there was a Big Mind and a Little Mind. And the Big Mind would allow you to consider deep thoughts, but the Little Mind would occupy you, so you could not be distracted. It would work crossword puzzles or play Solitaire, while the Big Mind would delve deep into the subjects I wanted to write about.

I have all the paintings and any decoration taken out of the room. I ask the management and housekeeping not to enter the room, just in case I’ve thrown a piece of paper on the floor, I don’t want it discarded. About every two months I get a note slipped under the door: “Dear Ms. Angelou, please let us change the linen. We think it may be moldy!”

But I’ve never slept there, I’m usually out of there by 2. And then I go home and I read what I’ve written that morning, and I try to edit then. Clean it up.

Easy reading is damn hard writing. But if it’s right, it’s easy. It’s the other way round, too. If it’s slovenly written, then it’s hard to read. It doesn’t give the reader what the careful writer can give the reader.

That pretty much wraps up why Kafka wrote the way he did and the subject matter he came up with for his novels. A tad depressed I’d say. So many writers and poets are though. Metamorphesis was one of the weirdest and depressing predicaments for a human being to find themselves in I can conceive of, and it is not classified as science fiction. He may have really felt like that!