Of the rare and extraordinary times in U.S. history when the U.S. government actively funded and promoted the arts on a national scale, two periods in particular stand out. There is the CIA’s role in channeling funds to avant-garde artists after the Second World War as part of the cultural front of the Cold War—a boon to painters, writers, and musicians, both witting and unwitting, and a strange way in which the intelligence community used the anti-communist left to head off what it saw as more dangerous and subversive trends. Most of the highly agenda-driven federal arts funding during the Cold War proceeded in secret until decades later, when long-sealed documents were declassified and agents began to tell their stories of the period.

Of a much less covertly political nature was the first major federal investment in the arts, begun under Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and championed in large part by his wife, Eleanor. Under the 1935-established Works Progress Administration (WPA)—which created thousands of jobs through large-scale public infrastructure projects—the Federal Project Number One took shape, an initiative, write Don Adams and Arlene Goldbard, that “marked the U.S. government’s first big, direct investment in cultural development.” The project’s goals “were clearly stated and democratic; they supported activities not already subsidized by private sector patrons… and they emphasized the interrelatedness of culture with all aspects of life, not the separateness of a rarefied art world.”

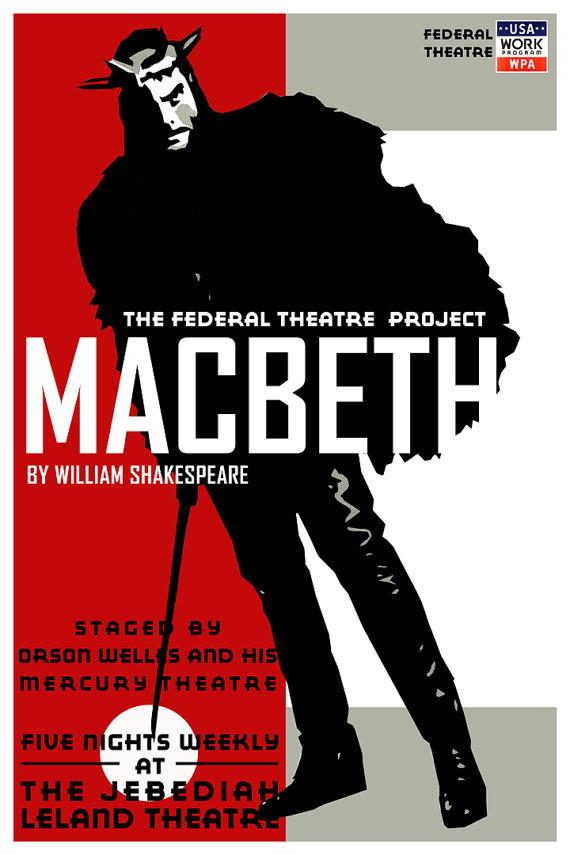

Under the program, known simply as “Federal One,” Orson Welles made his directorial debut, with a hugely popular, all-Black production of Macbeth; Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and others documented the Great Depression in their now iconic photographic series; Diego Rivera painted his huge murals of working people; folklorists Alan Lomax, Stetson Kennedy, and Harry Smith collected and recorded the popular music and stories of South; Zora Neale Hurston conducted anthropological field research in the Deep South and the Caribbean; American writers from Ralph Ellison to James Agee found support from the WPA. This is to name but a few of the most famous artists subsidized by the New Deal.

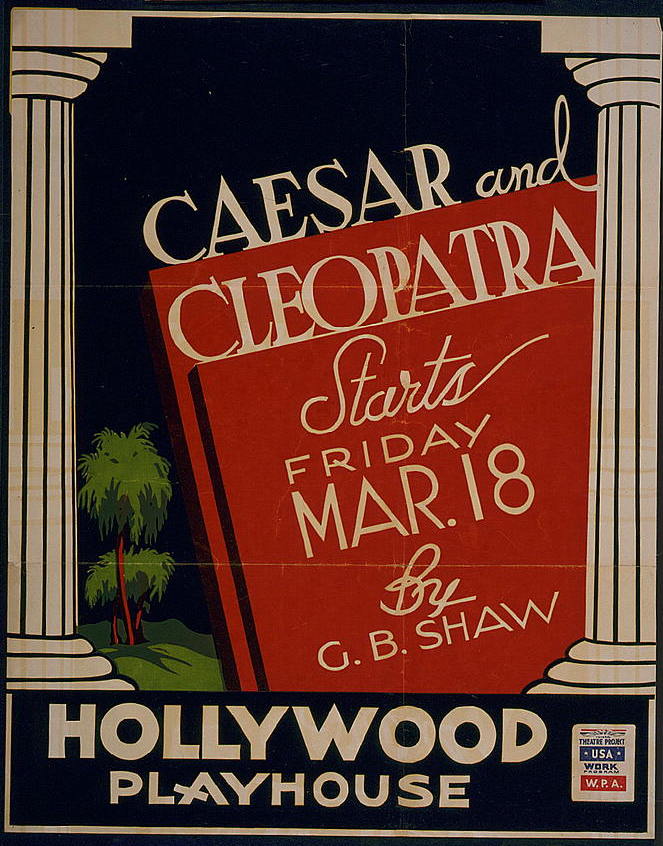

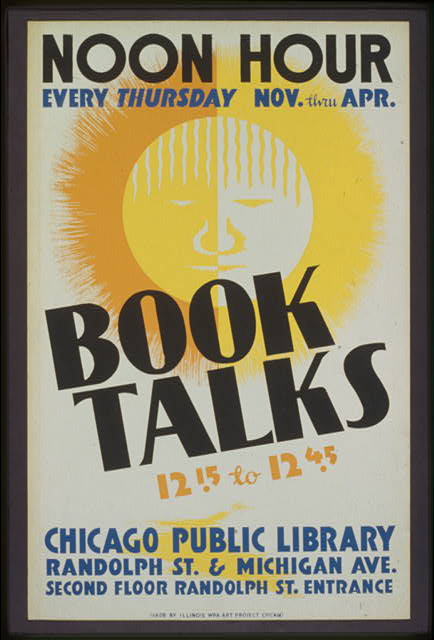

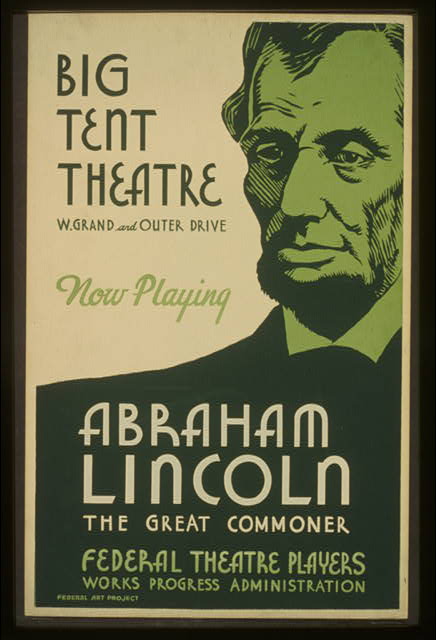

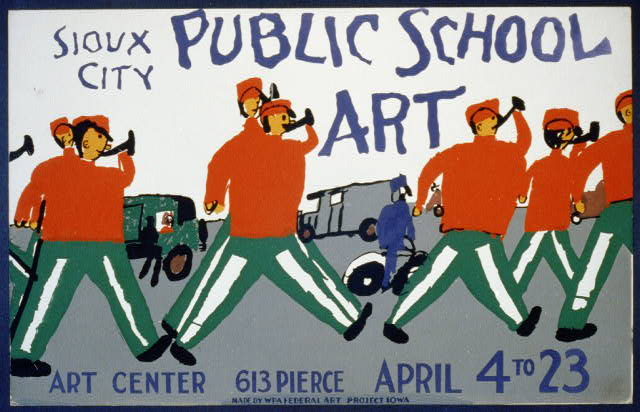

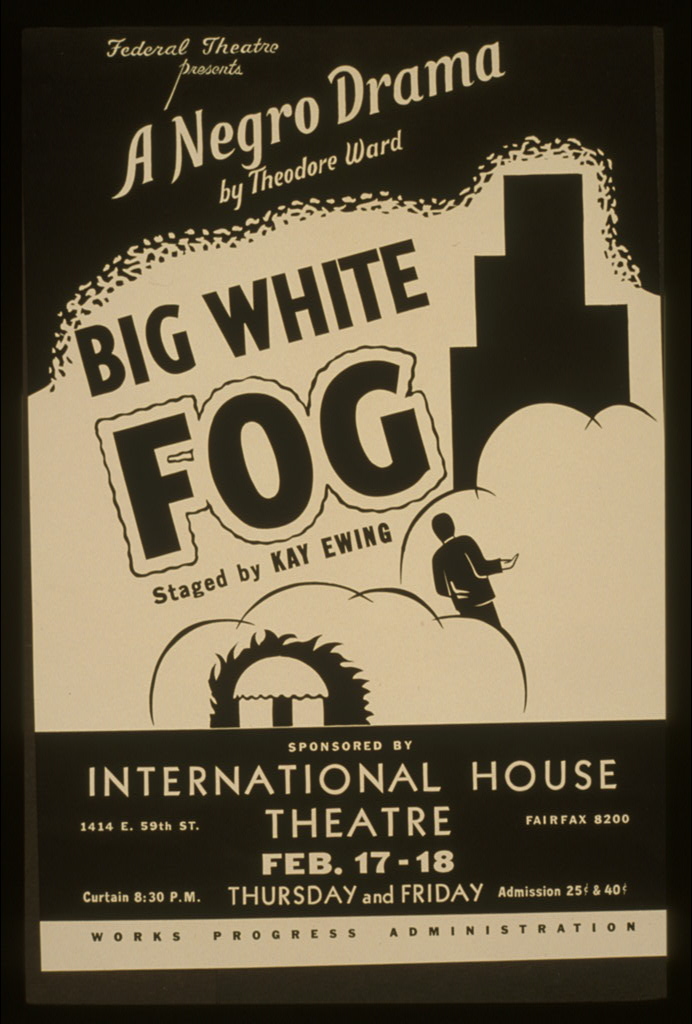

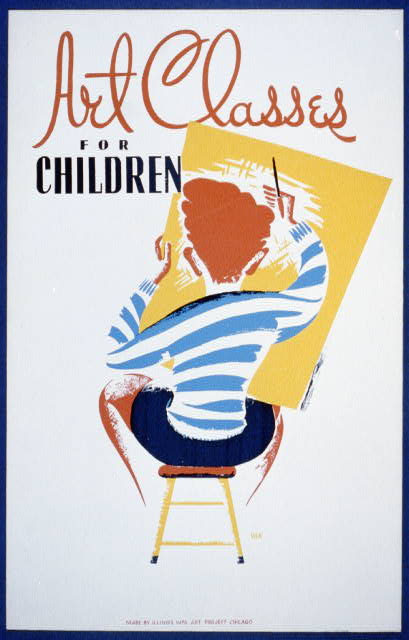

Thousands more whose names have gone unrecorded were able to fund community theater productions, literary lectures, art classes and many other works of cultural enrichment that kept people in the arts working, engaged whole communities, and gave ordinary Americans opportunities to participate in the arts and to find representation where they otherwise would be overlooked or ignored. Federal One not only “put legions of unemployed artists back to work,” writes George Washington University’s Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project, “but their creations would invariably entertain and enrich the larger population.”

“If FDR was only lukewarm about Federal One,” GWU points out, “his wife more than made up for it with her enthusiasm. Eleanor Roosevelt felt strongly that American society had not done enough to support the arts, and she viewed Federal One as a powerful tool with which to infuse art and culture into the daily lives of Americans.”

Now, thanks to the Library of Congress, we can see what that infusion of culture looked like in colorful poster form. Of the 2,000 WPA arts posters known to exist, the LoC has digitized over 900 produced between 1936 and 1943, “designed to publicize exhibits, community activities, theatrical productions, and health and education al programs in seventeen states and the District of Columbia.”

These posters, added to the Library’s holdings in the ‘40s, show us a nation that looked very different from the one we live in today—one in which the arts and culture thrived at a local and regional level and were not simply the preserves of celebrities, private wealth, and major corporations. Perhaps revisiting this past can give us a model to strive for in a more democratic, equitable future that values the arts as Eleanor Roosevelt and the WPA administrators did. Click here to browse the complete collection of WPA arts posters and to download digital images as JPEG or TIFF files.

Related Content:

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

What current social program are you willing to scale back or do away with to be able to afford this?

Who says we have to cut a social program?

Where did you find the Welles Macbeth poster? I’ve searched the collection, but can’t locate it. Could you post a direct link?

Don’t forget that the Library of Congress itself is an example of our tax dollars doing good work. But in all circumstances the documentation of history is fickle and erratic — note that it’s only a handful of the total FAP/WPA poster output that has been preserved. The significance of that period on this medium cannot be underestimated — see essay

Ah — as I suspected, links don’t appear. Search for “Meshed Histories: The Influence of Screen Printing on Social Movements” on the American Institute of Graphic Arts site.

it’s not on the LOC website, it’s a poster created by Rob Kelly in 2008

Search for welles macbeth mercury theatre wpa poster and click images

http://robkellyillustration.blogspot.com/2008/11/wpa-macbeth-2008.html

Tax the super-rich equitably and you won’t have to cut from the bottom.