Image by BBC Radio 6

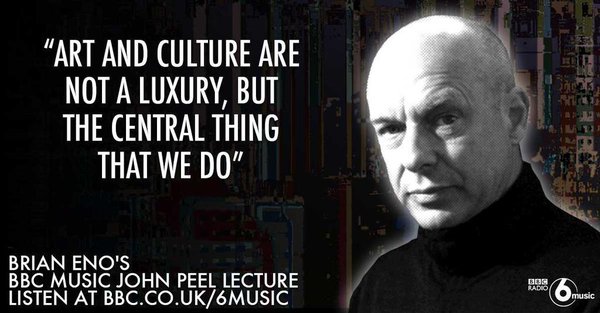

“Symphonies, perfume, sports cars, graffiti, needlepoint, monuments, tattoos, slang, Ming vases, doodles, poodles, apple strudels. Still life, Second Life, bed knobs and boob jobs” — why do we make any of these things? That question has driven much of the career (and indeed life) of Brian Eno, the man who invented ambient music and has brought his distinctive, at once intellectual and visceral sensibility to the work of bands like Roxy Music, U2, and Coldplay as well as the realm of visual art. Back in September, he laid out all the illuminating and entertaining answers at which he has thus far arrived in giving the BBC’s 2015 John Peel Lecture.

We featured Eno’s wide-ranging talk on the nature of art and culture, as well as its utility to the human race, back when the Beeb offered it streaming for a limited time only. But now they’ve made it freely available to download and listen to as you please: you can download the MP3 at this link.

You can also follow along, if you like, with the PDF transcript available here, which will certainly be of assistance when you go to look up all the people, ideas, works of art, and pieces of history Eno references along the way, including but not limited to the “STEM” subjects, Baked Alaska, black Chanel frocks, the Riemann hypothesis, Little Dorrit, Morse Peckham, Coronation Street, airplane simulators, the dole, Lord Reith, John Peel himself, Basic Income, Linux, and collective joy.

If you haven’t had enough Eno after that — and here at Open Culture, we never get enough Eno — have a look at and a listen to clips of a conversation he recently had with science writer Steven Johnson, all of which have an intellectual overlap with the Peel Lecture. The first deals with music, something this self-professed “non-musician” has done much more than his share of thinking about. The second has to do with punchlines, or rather, Eno’s conception of a piece of art, not as a thing with value in and of itself, but as a kind of punchline on the order of “I used to have a car like that.” (To hear its setup, you’ll have to watch the video.)

In the third, Johnson and Eno discuss an idea at the core of the Peel Lecture, Eno’s famous definition of culture, and later art: “Everything you don’t have to do.” That covers all the aforementioned symphonies, perfume, sports cars, graffiti, needlepoint, monuments, tattoos, slang, Ming vases, doodles, poodles, apple strudels, still life, Second Life, bed knobs and boob jobs: “All of those things are sort of unnecessary in the sense that we could all survive without doing any of them,” Eno says, “but in fact we don’t. We all engage with them.” And if you want to know why we should keep engaging with them, and in fact engage with them more vigorously than ever, Eno can tell you.

Related Content:

Jump Start Your Creative Process with Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies”

Revisit the Radio Sessions and Record Collection of Groundbreaking BBC DJ John Peel

Listen to “Brian Eno Day,” a 12-Hour Radio Show Spent With Eno & His Music (Recorded in 1988)

When Brian Eno & Other Artists Peed in Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

He does well here to undermine his notion of music as being crucially about the “differences” as soon as he’s presented it. There’s no denying the “surprise” element in the construction of music, as the interviewer mentions, and there is a thrill in music that seems completely new in some way or another, as Eno is discussing. But the opposite is equally true for many of us, as Eno points out: old, familiar melodies can sometimes be the most transporting.

Upon Paul Bley’s recent death, someone linked to an interview where he was emphasizing newness as the only criteria for good music–if you’ve played it before, it’s crap, is what he said in almost so many words. Much of music history is written that way–it’s only innovation that counts. But the experience of music in our lives doesn’t confirm that, we seem to sometimes–often–find “beauty” even in experiences that have been repeated many times over, as we dig deeper into the rich soil of old ground.