In the late 50s, a fearful, racist backlash against rock and roll, coupled with money-grubbing corporate payola, pushed out the blues and R&B that drove rock’s sound. In its place came easy listening orchestration more palatable to conservative white audiences. As sexy electric guitars gave way to string and horn sections, the comparatively aggressive sound of rock and roll seemed so much a passing fad that Decca’s senior A&R man rejected the Beatles’ demo in 1962, telling Brian Epstein, “guitar groups are on their way out.”

But it wasn’t only the blues, R&B, and doo wop revivalism of British Invasion bands that saved the American art form. It was also the often unintentional influence of audio engineers who—with their incessant tinkering and a number of happy accidents—created new sounds that defined the countercultural rock and roll of the 60s and 70s. Ironically, the two technical developments that most characterized those decades’ rock guitar sounds—the wah-wah and fuzz pedals—were originally marketed as ways to imitate strings, horns, and other non-rock and roll instruments.

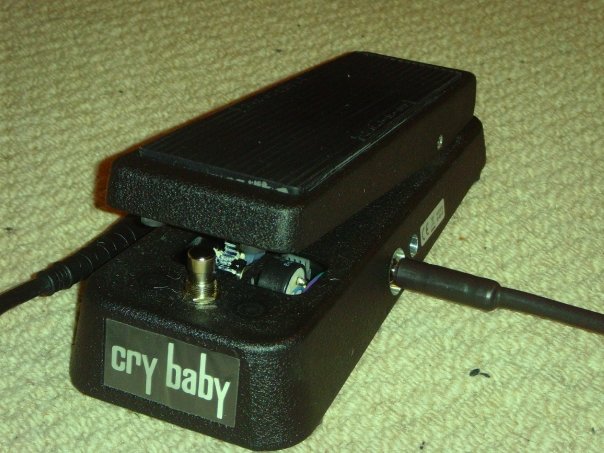

As you’ll learn in the documentary above, Cry Baby: The Pedal that Rocks the World, the wah-wah pedal, with its “waka-waka” sound so familiar from “Shaft” and 70s porn soundtracks, officially came into being in 1967, when the Thomas Organ company released the first incarnation of the effect. But before it acquired the brand name “Cry Baby” (still the name of the wah-wah pedal manufactured by Jim Dunlop), it went by the name “Clyde McCoy,” a backward-looking bit of branding that attempted to market the effect through nostalgia for pre-rock and roll music. Clyde McCoy was a jazz trumpet player known for his “wah-wah” muting technique on songs like “Sugar Blues” in the 20s, and the pedal was thought to mimic McCoy’s jazz-age effects. (McCoy himself had nothing to do with the marketing.)

Nonetheless the development of the wah-wah pedal came right out of the most current sixties’ technology made for the most current of acts, the Beatles. Increasingly drowned out by screaming crowds in larger and larger venues, the band required louder and louder amplifiers, and British amp company Vox obliged, creating the 100-watt “Super Beatle” amp in 1964 for their first U.S. tour. As Priceonomics details, when Thomas Organ scored a contract to manufacture the amps stateside, a young engineer named Brad Plunkett was given the task of learning how to make them for less. While experimenting with the smooth dial of a rotary potentiometer in place of an expensive switch, he discovered the wah-wah effect, then had the bright idea to combine the dial—which swept a resonant peak across the upper mid-range frequency—with the foot pedal of an organ.

The rest, as the cliché goes, is history—a fascinating history at that, one that leads from Elvis Presley studio guitarist Del Casher, to Frank Zappa, Clapton and Hendrix, and to dozens of 70s funk guitarists and beyond.

Art Thompson, editor of Guitar Player Magazine, notes in the star-studded Cry Baby documentary that prior to the invention of the wah-wah pedal, guitarists had a limited range of effects—tape delay, tremolo, spring reverb, and fuzz. Only one of these effects, however, was then available in pedal form, and that pedal, Gibson’s Maestro Fuzz-Tone, would also revolutionize the sound of sixties rock. But as you can hear in the short 1962 demonstration record above for the Maestro Fuzz-Tone, the fuzz effect was also marketed as a way of simulating other instruments: “Organ-like tones, mellow woodwinds, and whispering reeds,” says the announcer, “booming brass, and bell-clear horns.”

In fact, Keith Richards, in the Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”—the song credited with introducing the Maestro’s sound to rock and roll in 1965—originally recorded his fuzzed-out guitar part as a placeholder for a horn section. “But we didn’t have any horns,” he wrote in his autobiography, Life; “the fuzz tone had never been heard before anywhere, and that’s the sound that caught everybody’s attention.”

The assertion isn’t strictly true. While “Satisfaction” brought fuzz to the forefront, the effect first appeared, by accident, in 1961, with “a faulty connection in a mixing board,” writes William Weir in a history of fuzz for The Atlantic. Fuzz, “a term of art… came to define the sound of rock guitar,” but it first appeared in “the bass solo of country singer Marty Robbins on ‘Don’t Worry,’” an “otherwise sweet and mostly acoustic tune.” At the time, engineers argued over whether to leave the mistaken distortion in the mix. Luckily, they opted to keep it, and listeners loved it. When Nancy Sinatra asked engineer Glen Snoddy to replicate the sound, he recreated it in the form of the Maestro.

Guitarists had experimented deliberately with similar distortion effects since the very beginnings of rock and roll, cutting through their amp’s speakers—like Link Wray in his menacing classic instrumental “Rumble”—or pushing small, tube-powered amplifiers past their limits. But none of these experiments, nor the pedals that later emulated them, sound like the fuzz pedal, which achieves its buzzing effect by severely clipping the guitar’s signal. Later iterations from other manufacturers—the Tone Bender, Big Muff, and Fuzz Face—have acquired their own cache, in large part because of Jimi Hendrix’s heavy use of various fuzz pedals throughout his career. “Like the shop talk of wine enthusiasts,” writes Weir, “discussions among distortion cognoscenti on nuances of tone can baffle outsiders.”

Indeed. Those early experiments with effects pedals now fetch upwards of several thousand dollars on the vintage market. And a recent boom in boutique pedals has sent prices for handcrafted replicas of those original models—along with several innovative new designs—into the hundreds of dollars for a single pedal. (One handmade overdrive, the Klon Centaur, has become the most imitated of modern pedals; originals can go for up to two thousand dollars.) The specialization of effects pedal technology, and the hefty pricing for vintage and contemporary effects alike, can be daunting for beginning guitarists who want to sound like their favorite players. But what early players and engineers figured out still holds true—musical innovation is all about creating original sounds by experimenting with whatever you have at hand.

Cry Baby: The Pedal that Rocks the World has been added to our list of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

via Priceonomics

Related Content:

The “Amen Break”: The Most Famous 6‑Second Drum Loop & How It Spawned a Sampling Revolution

All Hail the Beat: How the 1980 Roland TR-808 Drum Machine Changed Pop Music

A Brief History of Sampling: From the Beatles to the Beastie Boys

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Absolutely, never noticed that! So much brilliant music with fuzz; it’s also on Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues (not so prominent, but it’s there), recorded before Satisfaction along with other cool surf stuff…60s Garage Punk and Psyck wouldn’t have been the same without it! Great posting, BTW..

You completely ignore the work of Del Kacher (now spelled “Casher”, who actually ideated, invented and developed the wah-wah pedal! Shame on you!!!! I worked many gigs with Del during the period when he was develping the pedal and other sound-altering devices. Del was, and to myopinion still is one of the world’s greatest technical guitarists. I did many sessions in his old studio “California Sound Recorders”. You have done a brilliant man a sad disservice by ignoring him.