Like many American stories, the story of the National Parks begins with pillage, death, deep cultural misunderstanding, and venture capitalism. According to Ken Burns’ film series The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, we can date the idea back to 1851, with the “discovery” of Yosemite by a marauding armed battalion who entered the land “searching for Indians, intent on driving the natives from their homelands and onto reservations.” The Mariposa Battalion, led by Captain James D. Savage, set fire to the Indians’ homes and storehouses after they had retreated to the mountains, “in order to starve them into submission.”

One member of the battalion, a doctor named Lafayette Bunnell, found himself entranced by the scenery amidst this destruction. “As I looked, a peculiar exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being,” he wrote in his later accounts, “and I found myself in tears with emotion.” He named the place “Yosemite,” thinking it was the name of the Indian tribe the soldiers sought to force out or eradicate. The word, it turned out “meant something entirely different,” referring to people who should be feared: “It means, ‘they are killers.’”

In 1855, a failed English gold prospector turned the place into a tourist attraction, and people flooded West to see it, prompting New York worthies like Horace Greeley and Frederick Law Olmsted to lobby for its federal protection. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln deeded Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove, with its giant sequoias, to the state of California. Ever since then, National Parks have been threatened—if not by the occasional political candidate and his billionaire backers hoping to privatize the land, then by oil and gas drilling, and by fire, rising seas, or other effects of climate change. Though the U.S. emptied many of the parks of their inhabitants, it is ironically only the actions of the federal government that prevents the process begun by the Mariposa Battalion from reaching its conclusion in the total despoliation of these landscapes. It is these landscapes that have most come to symbolize the national character, whether as background in Frederic Remington’s paintings of the Indian Wars or in the photographs of Ansel Adams, who began and sustained his career in Yosemite Valley. “Yosemite National Park,” writes the National Park Service’s website,” was Adams’ chief inspiration.”

Adams first became interested in visiting the National Park when he read In the Heart of the Sierras by James Hutchings—that failed English gold prospector. Thereafter, Adams photographed National Parks almost ritually, and in 1941, the National Park Service commissioned Adams to create a photo mural for the Department of the Interior Building in DC. The theme, the National Archives tells us, was to be “nature as exemplified and protected in the U.S. National Parks. The project was halted because of World War II and never resumed.” It must have felt like an especially sacred duty for Adams, who traveled the country photographing the Grand Canyon, Grand Teton, Kings Canyon, Mesa Verde, Rocky Mountain, Yellowstone, Yosemite, Carlsbad Caverns, Glacier, and Zion National Parks; Death Valley, Saguro, and Canyon de Chelly National Monuments,” and other locations like the Boulder (now Hoover) Dam and desert vistas in New Mexico.

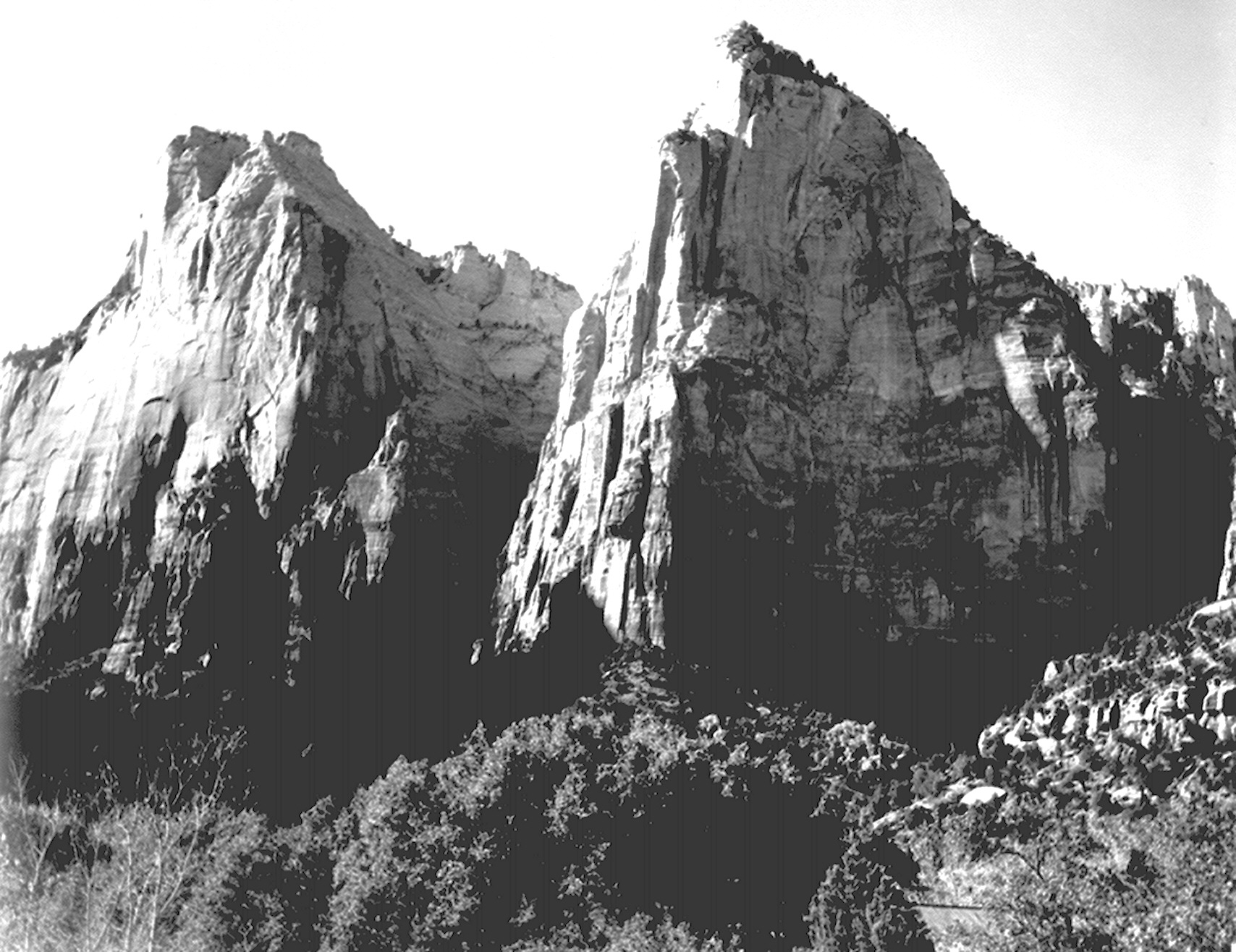

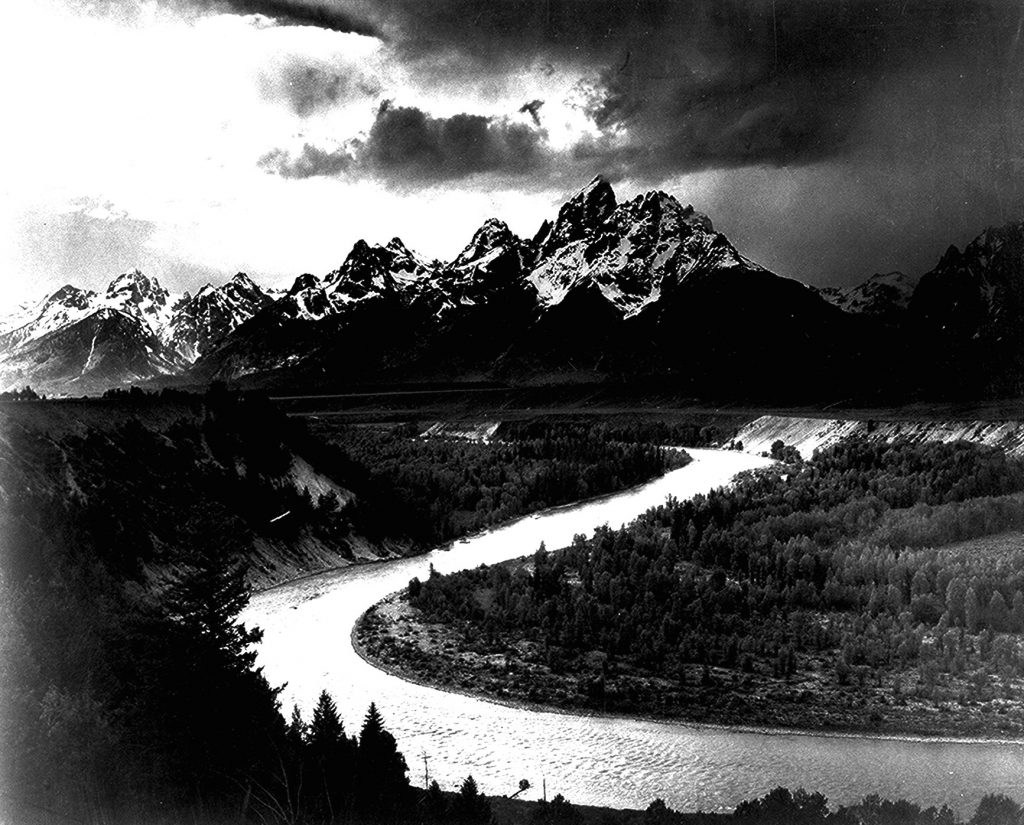

The photographs you see here are among the 226 taken by Adams for the project. They are now housed at the National Archives, and you can freely view them online or order prints at their site. At the top, we see a snow-covered tree from an apple orchard in Half Dome, Yosemite, where Adams had his first photographic “visualization” in 1927. Below it, the “Court of the Patriarchs” in Zion National Park, Utah. Further down, we have a breathtaking vision of the serpentine Grand Canyon, and just above, one of the few manmade structures, “Cliff Palace” at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. And here can you see a photograph of the Snake River in Grand Teton National Park.

The mural project may have been abandoned, but Adams never stopped photographing the parks, nor advocating for their protection and, in fact, the protection of “the entire environment,” as he told a Playboy interviewer in 1983. “Only two and a half percent of the land in this country is protected,” said Adams then: “Not only are we being fought in trying to extend that two and a half percent to include other important or fragile areas but we are having to fight to protect that small two and a half percent. It is horrifying that we have to fight our own Government to save our environment.”

You can peruse the collection of Ansel Adams’ national park photos here.

Related Content:

Ansel Adams Reveals His Creative Process in 1958 Documentary

200 Ansel Adams Photographs Expose the Rigors of Life in Japanese Internment Camps During WW II

How to Take Photographs Like Ansel Adams: The Master Explains The Art of “Visualization”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It’s nice to see the photos all together, and it gives us a good opportunity to reexamine Ansel Adams’s body of work, understand his compositional style, and see how he influenced the work of landscape photographers around the world to this day.

The quality of many of these scans is very poor. It looks like they scanned from prints not negatives, and faded prints at that. They weren’t always in focus or flat on the scanner glass. Such a shame.

Kevin

They may have deliberately used lower quality scans for online viewing to avoid people taking high quality images for themselves. After all selling prints is still something they want to do as a result of this online presentation.

muy buena información… gracias

Thank you for sharing some history and access to beautiful photographs. Maybe you could forward this to our U.S. Congress.