Some of the most rigorous moral thinkers of the past century have spent time on the wrong side of questions they deemed of vital importance. Mohandas Gandhi, for example, at first remained loyal to the British, manifesting many of the vicious prejudices of the Empire against Black South Africans and lobbying for Indians to serve in the war against the Zulu. Maya Jasanoff in New Republic describes Gandhi during this period of his life as a “crank.” At the same time, he developed his philosophy of non-violent resistance, or satyagraha, in South Africa as an Indian suffering the injustices inflicted upon his countrymen by both the Boers and the British.

Gandhi’s sometime contradictory stances may be in part understood by his rather aristocratic heritage and by the warm welcome he first received in London when he left his family, his caste, and his wife and child in India to attend law school in 1888. And yet it is in London that he first began to change his views, becoming a staunch vegetarian and encountering theosophy, Christianity, and many of the contemporary writers who would shift his perspective over time. Gandhi received a very different reception in England when he returned in 1931, the de facto leader of a burgeoning revolutionary movement in India whose example was so important to both the South African and U.S. civil rights movements of succeeding decades.

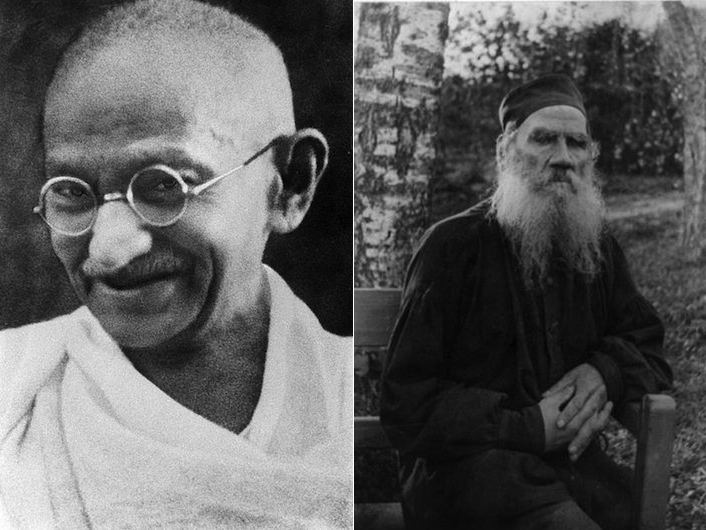

One of the writers who most deeply guided Gandhi’s political, spiritual, and philosophical evolution, Leo Tolstoy, experienced his own dramatic transformation, from landed aristocrat to social radical, and also renounced property and position to advocate strenuously for social equality. Gandhi eagerly read Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You, the novelist’s statement of Christian anarchism. The book, Gandhi wrote in his autobiography, “left an abiding impression on me.” After further study of Tolstoy’s religious writing, he “began to realize more and more the infinite possibilities of universal love.”

It was in England, not India, where Gandhi first read “A Letter to a Hindu,” Tolstoy’s 1908 reply to a note from Indian revolutionary Taraknath Das on the question of Indian independence. Tolstoy divides his lengthy, thoughtful “Letter” into short chapters, each of which begins with a quotation from the Vedas. “Indeed,” writes Maria Popova, the missive “puts in glaring perspective the nuanceless and hasty op-eds of our time.” It so affected Gandhi that, in 1909, he wrote to Tolstoy, thus beginning a correspondence between the two that lasted through the following year. “I take the liberty of inviting your attention to what has been going on in the Transvaal for nearly three years,” begins Gandhi’s first letter, somewhat abruptly, “There is in that Colony a British Indian population of nearly 13,000. These Indians have, for several years, labored under various legal disabilities.”

The prejudice against color and in some respects against Asians is intense in that Colony….The climax was reached three years ago, with a law that many others and I considered to be degrading and calculated to unman those to whom it was applicable. I felt that submission to a law of this nature was inconsistent with the spirit of true religion. Some of my friends and I were and still are firm believers in the doctrine of nonresistance to evil. I had the privilege of studying your writings also, which left a deep impression on my mind.

Gandhi refers to a law forcing the Indian population in South Africa to register with the authorities. He goes on to inquire about the authenticity of the “Letter” and asks permission to translate it, with payment, and to omit a negative reference to reincarnation that offended him. Tolstoy responded a few months later, in 1910, allowing the translation free of charge, and allowing the omission, with the qualification that he believed “faith in re-birth will never restrain mankind as much as faith in the immortality of the soul and in divine truth in love.” Overall, however, he expresses solidarity, greeting Gandhi “fraternally” and writing,

God help our dear brothers and co-workers in the Transvaal! Among us, too, this fight between gentleness and brutality, between humility and love and pride and violence, makes itself ever more strongly felt, especially in a sharp collision between religious duty and the State laws, expressed by refusals to perform military service.

The two continued to write to each other, Gandhi sending Tolstoy a copy of his Indian Home Rule and the translated “Letter,” and Tolstoy expounding at length on the errors—and what he saw as the superior characteristics—of Christian doctrine. You can read their full correspondence here, along with Tolstoy’s “Letter to a Hindu” and Gandhi’s introduction to his edition. Despite their religious differences, the exchange further galvanized Gandhi’s passive resistance movement, and in 1910, he founded a community called “Tolstoy Farm” near Johannesburg.

Gandhi’s views on African independence would change, and Nelson Mandela later adopted Gandhi and the Indian independence movement as a standard for the anti-apartheid movement. We’re well aware, of course, of Gandhi’s influence on Martin Luther King, Jr. For his part, Gandhi wrote glowingly of Tolstoy, and the model the novelist provided for his own anti-colonial campaign. In a speech 18 years later, he said, “When I went to England, I was a votary of violence, I had faith in it and none in nonviolence.” After reading Tolstoy, “that lack of faith in nonviolence vanished…Tolstoy was the very embodiment of truth in this age. He strove uncompromisingly to follow truth as he saw it, making no attempt to conceal or dilute what he believed to be the truth. He stated what he felt to be the truth without caring whether it would hurt or please the people or whether it would be welcome to the mighty emperor. Tolstoy was a great advocate of nonviolence in his age.”

Related Content:

Hear Gandhi’s Famous Speech on the Existence of God (1931)

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Leo Tolstoy’s Masochistic Diary: I Am Guilty of “Sloth,” “Cowardice” & “Sissiness” (1851)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How can we apply non violence to the fundamental religious based groups who are driving whole populations out of their countries to be forced upon other countries which creates more violence from a non violent sectors.

Non violence is the prerequisite to stop violence amongst any groups, not just fundamental religious groups. It is the fundamentalism itself that creates a chism if it doesn’t incorporate nonviolence. Once violent, it promotes violent reaction, or proactions. the question is how to reduce or remove violence as a form of existence in human beings. Socio-economic struggles promote violence as a means of survival (of the fittest). If we can reduce that struggle to survive, we can reduce the violence.

On a lighter note, my wonderful tablet likes to spell words for me and that, along with the lack of early morning coffee may result in dropping in a somewhat inappropriate word where ‘chasm’ was the intended one. LOL

I enjoyed this, thank you Josh Jones. George Orwell wrote an insightful essay on Gandhi which provided a candid assessment of the man and reshaped my understanding of him. Pacifism is an admirable idea, though not always pragmatic. Gandhi’s suggestion about the holocaust is shocking: collective suicide. If you want a fuller view of the icon, read Orwell. Essay link here http://www.orwell.ru/library/reviews/gandhi/english/e_gandhi

@MylinhShattan http://www.treehouseletter.com