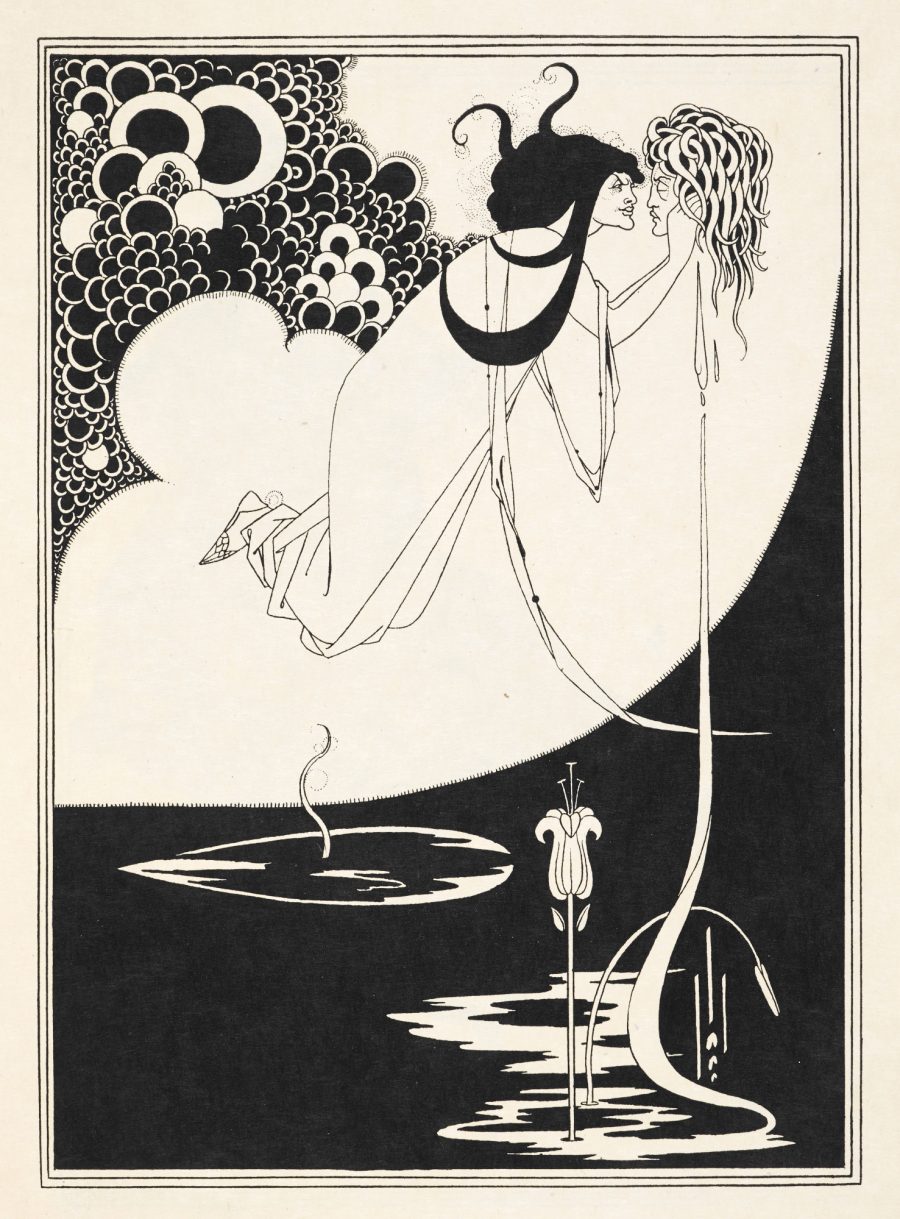

In William Faulkner’s 1936 Absalom, Absalom!, one of the novel’s most erudite characters paints a picture of a Gothic scene by comparing it to an Aubrey Beardsley drawing. References to Beardsley also appear in other Faulkner novels, and the English artist of the late nineteenth century also influenced the American novelist’s visual art. Like Faulkner, Beardsley was irresistibly drawn to “the grotesque and the erotic,” as The Paris Review writes, and his work was highly favored among French and British poets of his day. The modernist’s appreciation of Beardsley was about more than Faulkner’s own youthful romance with French Symbolist art and morbid romantic verse, however. Beardsley created a modern Gothic aesthetic that came to represent both Art Nouveau and decadent, transgressive literature for decades to come, presenting a seductive visual challenge to the repression of Victorian respectability.

Beardsley was a young aesthete with a literary imagination. In his short career—he died at the age of 25—he illustrated many of the works of Edgar Allan Poe, forefather of the American Gothic.

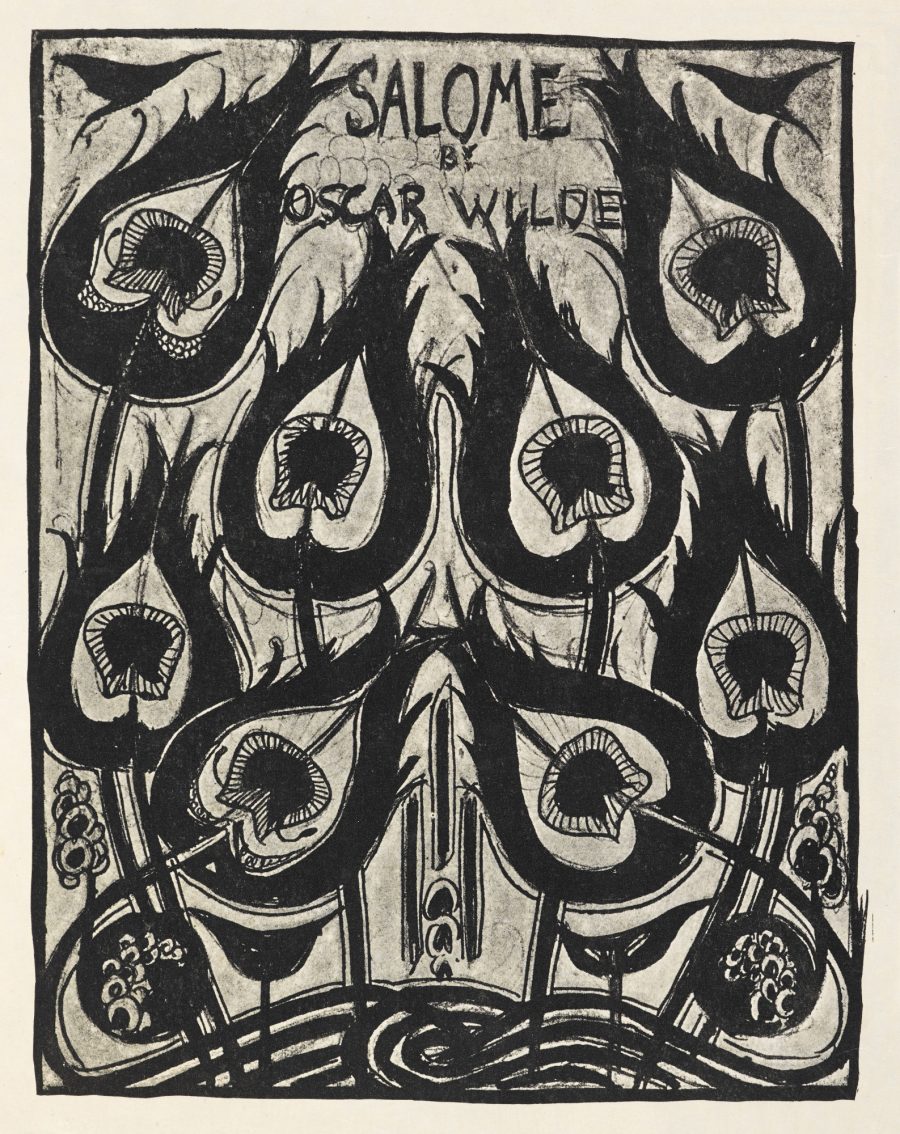

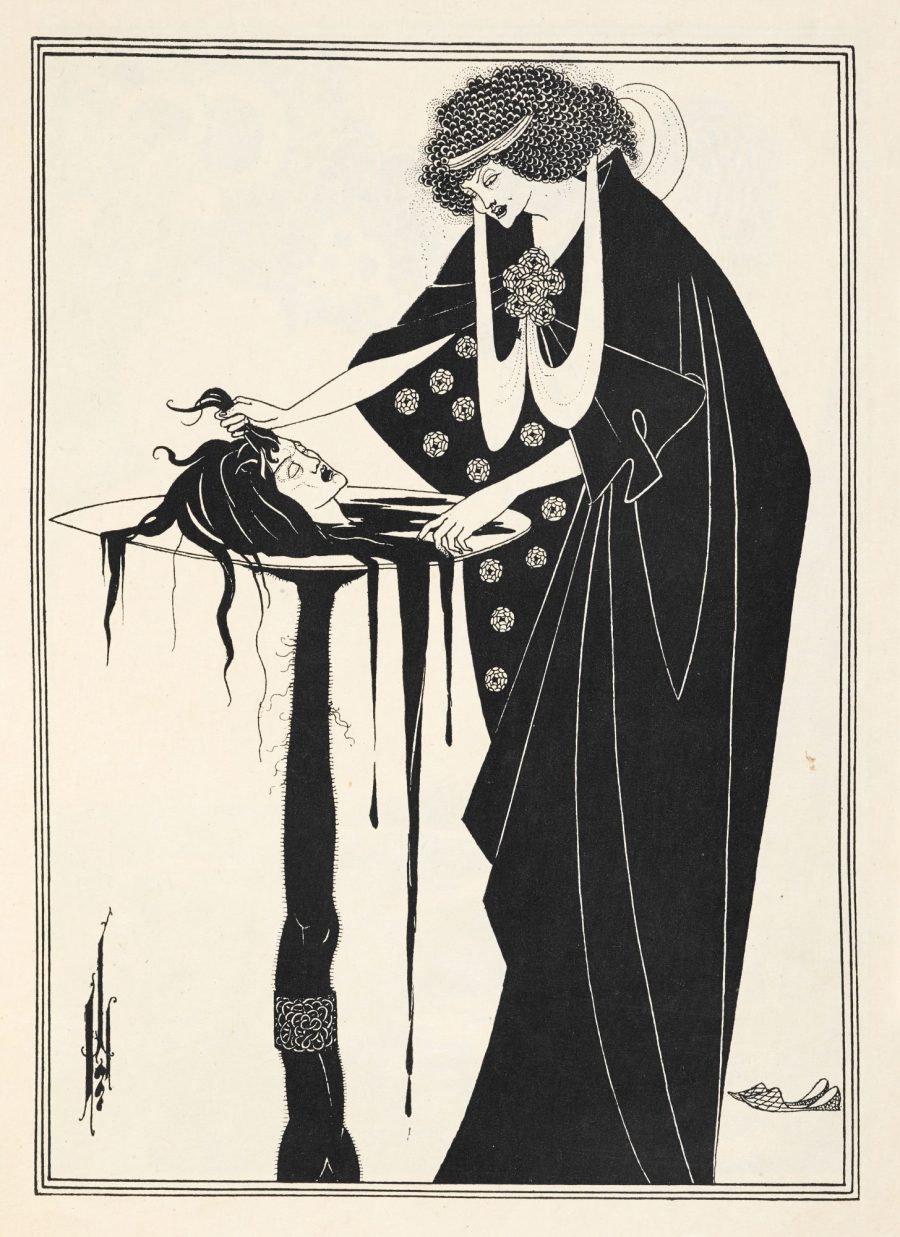

Beardsley also famously illustrated Oscar Wilde’s scandalous drama, Salome in 1893, to the surprise of its author, who later inscribed an illustrated copy with the words, “For the only artist who, besides myself, knows what the Dance of the Seven Veils is, and can see that invisible dance.” Beardsley’s drawings first appeared in an art magazine called The Studio, then the following year in an English publication of the text.

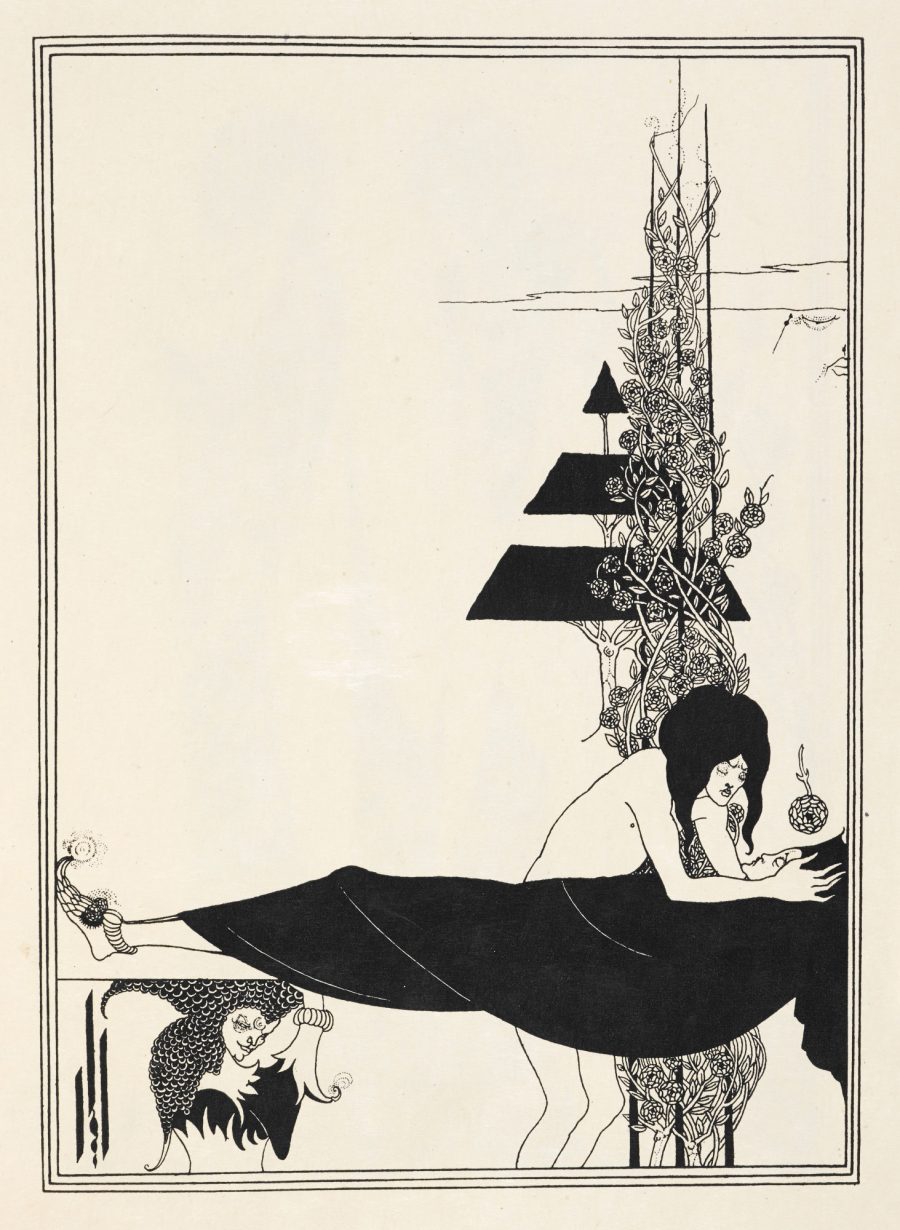

Beardsley and Wilde’s joint creation embraced the macabre and flaunted Victorian sexual norms. After an abrupt cancellation of Salome’s planned opening in England, the illustrated edition introduced British readers to the play’s unsettling themes. The British Library quotes critic Peter Raby, who argues, “Beardsley gave the text its first true public and modern performance, placing it firmly within the 1890s – a disturbing framework for the dark elements of cruelty and eroticism, and of the deliberate ambiguity and blurring of gender, which he released from Wilde’s play as though he were opening Pandora’s box.”

Wilde’s play was ostensibly banned for its portrayal of Biblical characters, prohibited on stage at the time. Furthermore, it “struck a nerve,” writes Yelena Primorac at Victorian Web, with its “portrayal of woman in extreme opposition to the traditional notion of virtuous, pure, clean and asexual womanhood the Victorians felt comfortable living with.” Wilde was at first concerned that the illustrations, with their suggestively posed figures and frankly sexual and violent images, would “reduce the text to the role of ‘illustrating Aubrey’s illustrations.’” (You can see some of the more suggestive images here.)

Indeed, it is hard to think of Wilde’s text and Beardsley’s images as existing independently of each other, so closely have they been identified for over a hundred years. And yet the drawings don’t always correspond to the narrative. Instead they present a kind of parallel text, itself densely woven with visual and literary allusions, many of them drawn from Symbolist preoccupations—with women’s hair, for example, as an alluring and threatening emblem of unrestrained female sexuality. Published in full in 1894, in an English translation of Wilde’s original French text, the Beardsley-illustrated Salome contained 16 plates, some of them tamed or censored by the publishers. Read the full text, with drawings, here, and see a gallery of Beardsley’s original uncensored illustrations at the British Library.

Related Content:

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

Stephen Fry Reads Oscar Wilde’s Children’s Story “The Happy Prince”

Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Alberto Martini’s Haunting Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1901–1944)

Pablo Picasso’s Tender Illustrations For Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (1934)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

who gave you the quarter? All of them