As a writer, a thinker, and a human being, James Baldwin knew few boundaries. The black, gay, expatriate author of such still-read books as Go Tell it on the Mountain and The Fire Next Time set an example for all who have since sought to break free of the strictures imposed upon them by their society, their history, or even their craft. Baldwin wrote not just novels but essays, plays, poetry, and even a children’s book, which you see a bit of here today.

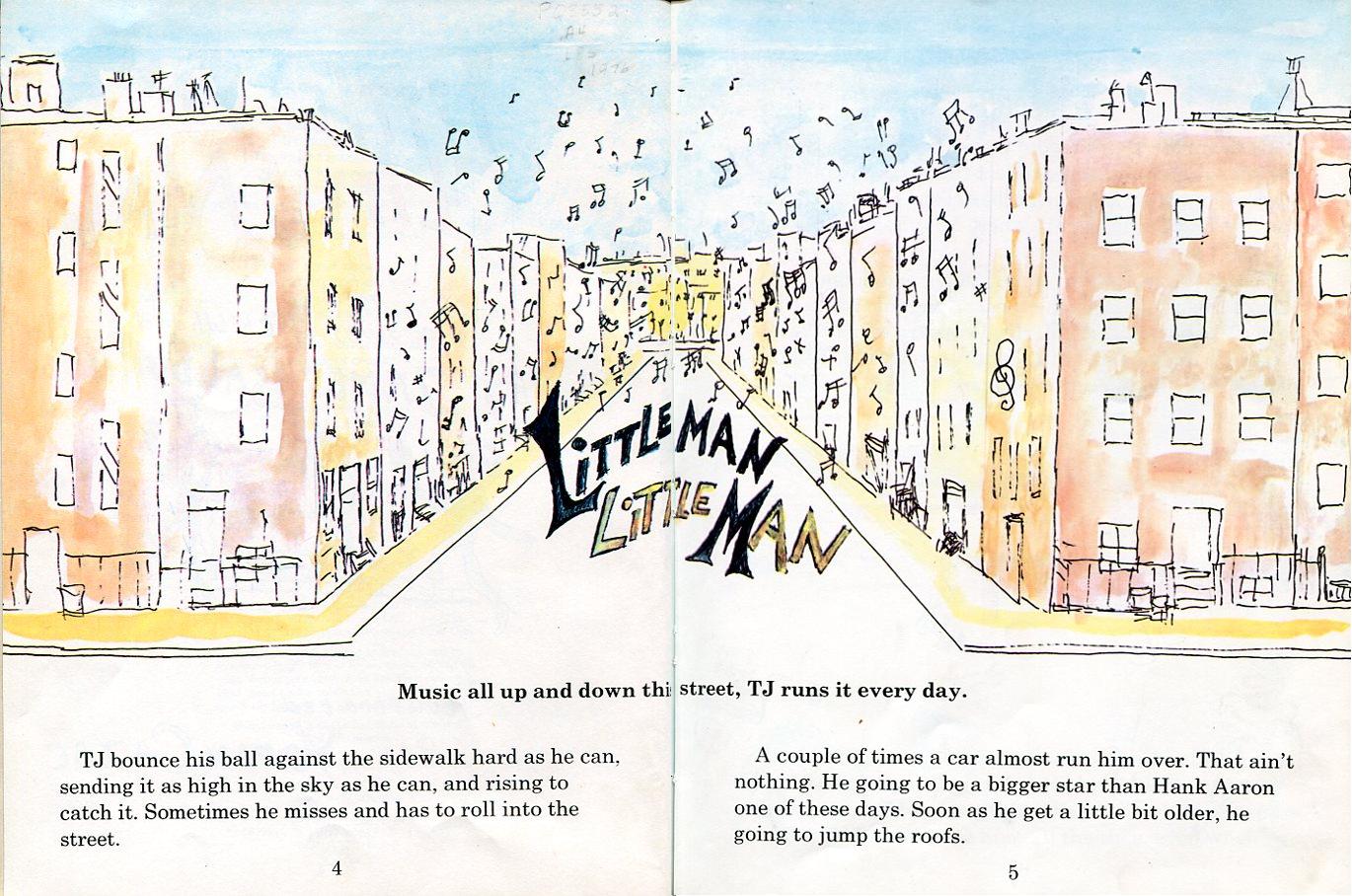

Little Man Little Man: A Story of Childhood came out in 1976, a productive year for Baldwin which also saw the publication of The Devil Finds Work, a book of writing on film (yet another form on which he exerted his own kind of socially critical mastery). In Little Man, he writes not about a highly visual medium, but in a highly visual medium: young children delight in lively illustrations, and they must have especially delighted in the ones here (more of which you can see in this gallery), drawn by French artist Yoran Cazac with a kind of mature childishness.

Those same adjectives might apply to Baldwin’s writing here as well, since he aims his story toward children, talking not down at them but straight at them, in their very own language: “TJ bounce his ball as hard as he can, sending it as high in the sky as he can, and rising to catch it.” So goes the introduction to the main character, a four-year-old boy living in Harlem whom Baldwin based on his nephew. “Sometimes he misses and has to roll into the street. A couple of times a car almost run him over. That ain’t nothing.”

TJ and WT, his older pal from the neighborhood, take their scrapes throughout the course of this short book, but they also have a rich experience — and thus provide, for their readers young and old, a rich experience — of the unique time and place in which they find themselves growing up. Their working-class Harlem childhood obviously has its pains, but it has its joys too. “TJ’s Daddy try to act mean, but he ain’t mean,” Baldwin writes. “Sometime take TJ to the movies and he take him to the beach and he took him to the Apollo Theatre, so he could see blind Stevie Wonder. ‘I want you to be proud of your people,’ TJ’s Daddy always say.”

At We Too Were Children, Ariel S. Winter highlights the book’s dedication “to the eminent African-American artist Beauford Delaney. Baldwin met Delaney when he was fourteen, the first self-supporting artist he had ever met, and like Baldwin, Delaney was black and homosexual. Delaney became a mentor to Baldwin, who often spoke of him as a ‘spiritual father,’ ” and “it was Delaney who introduced Baldwin to Yoran Cazac in Paris.” Baldwin became godfather to Cazac’s third child, and Cazac, of course, became the man who gave artistic life to Baldwin’s vision of childhood itself.

You can pick up your own copy of Little Man Little Man: A Story of Childhood on Amazon.

Related Content:

Langston Hughes Presents the History of Jazz in an Illustrated Children’s Book (1955)

Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958)

James Baldwin Debates Malcolm X (1963) and William F. Buckley (1965): Vintage Video & Audio

James Baldwin: Witty, Fiery in Berkeley, 1979

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply