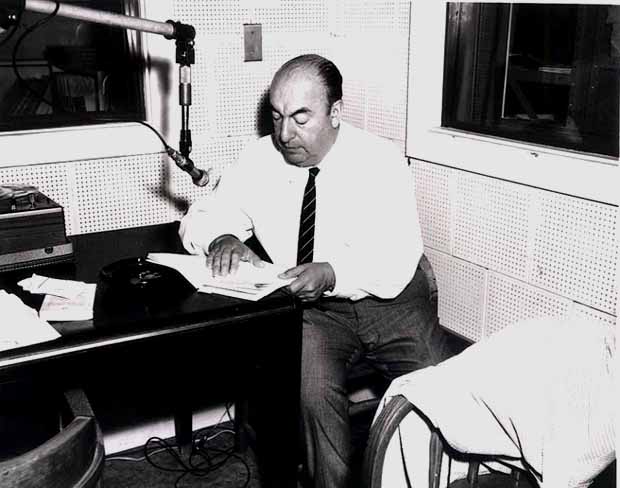

Image by Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons

“It is good,” wrote Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, “at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest.” I find myself astonished Neruda himself ever found time to rest, and to compose the hundreds of surrealist poems that made him a national celebrity at 20 years of age and an internationally renowned Nobel Prize winner at age 67. In 1927, Neruda began his long career as a diplomat—“in the Latin American tradition,” writes the American Academy of Poets, “of honoring poets with diplomatic assignments.” Throughout his life, his political commitments were intense and unswerving. His many diplomatic appointments (in civil war-torn Spain and elsewhere), his term in the Chilean senate, his exile, and then his return to diplomatic service in his native land might have constituted a life’s work in its own right.

But Neruda’s loyalty to poetry—“a poetry as impure as the clothing we wear, or our bodies”—defines his life and legacy above all else. “Of all the overlapping and competing facets of his life,” writes Erin Becker, “amidst all the contradictions and the hypocrisies, Neruda was always a poet first… his belief in the beauty of life and words always comes through, even in his most political work.” Neruda himself declared, “I have never thought of my life as divided between poetry and politics.” Instead, he believed that his work spoke not for itself, but for the people. As the Nobel Committee put it, Neruda’s poetry communicated “with the action of an elemental force” that “brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams.”

On September 5, 1971, just a few days before he accepted the Nobel, Neruda gave his first public reading in English, on the radio program Comment. You can hear him above introduce and read his very Whitmanesque poem, “Birth.” Neruda had previously addressed English-speaking readers when, after a longtime ban, he visited the states in 1966 and spoke to an audience at New York’s 92nd St. Y. Then, he introduced himself in English but would only read his poetry in Spanish. Here—“having entirely no confidence in my reading”—he nonetheless reads translations of his work by “some of my very best friends,” mainly his primary translator in English, Ben Belitt. While Belitt has been “accused of taking liberties” with Neruda’s verse, the poet himself obviously endorsed his translations.

Belitt’s renderings of Neruda’s learned, yet earthy Spanish have become the standard way most of us encounter the poet in English. The publication of the 1974 dual-language anthology Five Decades: Poems 1925–1970, was to have been “festive,” wrote Belitt in his preface, in honor of the poet’s 70th birthday. Sadly, instead, it was a posthumous celebration of Neruda’s work. The poet died in September of 1973, two years after the reading above and just twelve days after the CIA helped overthrow Salvador Allende and install the brutal dictator Augusto Pinochet. As Oscar Guardiola-Rivera writes colorfully in The Guardian, the details of Neruda’s political life are fodder for activists, “Google-bombs waiting to be set off by a new generation of networked freedom fighters.” His poetic voice, however, speaks to and for the multitudes, with—as Neruda wrote in “Toward an Impure Poetry”—“the mandates of touch, smell, taste, sight, hearing, the passion for justice, sexual desire… [and] the sumptuous appeal of the tactile.”

Neruda’s reading will be added to the Poetry section of our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

via Past Daily

Related Content:

Pablo Neruda’s Historic First Reading in the US (1966)

“The Me Bird” by Pablo Neruda: An Animated Interpretation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Pieces on Neruda are always a welcome find. Thanks for this, love this site.