When it comes to theories of artistic lineage, few have been as influential as Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence, in which the august literary critic argues, “Poetic Influence—when it involves two strong, authentic poets—always proceeds by a misreading of the prior poet, an act of creative correction that is actually and necessarily a misinterpretation.” This kind of misreading—what Bloom calls “misprision”—often takes place between two artists separated by vast gulfs of time and space: the influence of Dante on T.S. Eliot, for example, or of Shakespeare on Herman Melville.

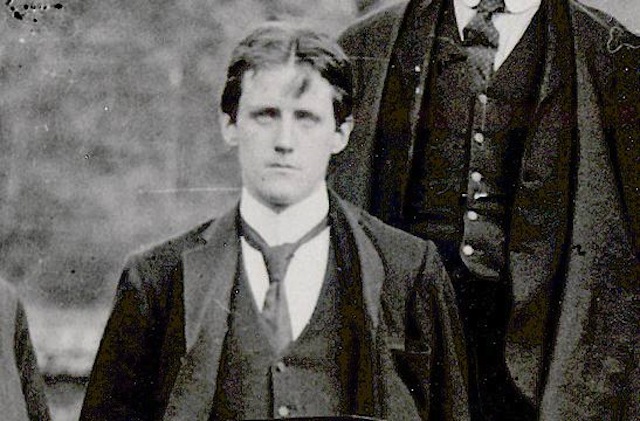

When we come to a study of James Joyce (1882–1941), however, we find the groundbreaking modernist corresponding directly with one of his foremost literary heroes, Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906), whom Maria Popova calls Joyce’s “spiritual and mental ancestor.” As Bloom points out, Joyce described Ibsen’s work as being “of universal import.” He extolled and defended Ibsen’s then-controversial work in his student days, both in a 1900 lecture he delivered at University College, Dublin, and in an essay he published that same year in the London journal Fortnightly Review. (See the young Joyce above in 1902, at 20 years of age.)

Joyce’s article, “Ibsen’s New Drama,” focused on the playwright’s latest, When We Dead Awaken, and was warmly received by Ibsen himself, who—through his English translator William Archer—described the essay as “velvillig,” or “benevolent.” Archer conveyed Ibsen’s sentiments in a letter soon after the essay’s publication, and thereafter, Joyce’s essay—writes the James Joyce Centre—was “no longer just a review but a review that Ibsen had read and praised.”

Thus began a three-year correspondence between Joyce and Archer, and a friendly relationship—at some remove—between Joyce and Ibsen. In 1901, on the playwright’s 73rd birthday, Joyce wrote a letter to Ibsen directly. He mentions the circumstances of the review and expresses much youthful admiration, self-confidence, and gratitude for Ibsen’s response. The young Joyce laments that his “immature and hasty article” came to Ibsen’s attention first, “rather than something better,” and boasts, “I have claimed for you your rightful place in the history of drama.”

Read the letter in full below, in all its exuberant egotism. According to James Joyce A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work, as he matured, the novelist “drew upon Ibsen less for creative encouragement than for psychological inspiration. In Joyce’s mind, Ibsen remained the model of the artist who defies conventional creative approaches and who remains true to the demands of an individual aesthetic.” Whether Joyce “misread” and “creatively corrected” Ibsen is a question I leave for others. You can read many more “fan letters” written by other famous authors to their literary heroes—including George R.R. Martin to Stan Lee, Charles Dickens to George Eliot, and Ray Bradbury to Robert Heinlein—at Flavorwire.

Honoured Sir,

I write to you to give you greeting on your seventy-third birthday and to join my voice to those of your well-wishers in all lands. You may remember that shortly after the publication of your latest play ‘When We Dead Awaken’, an appreciation of it appeared in one of the English reviews — The Fortnightly Review — over my name. I know that you have seen it because some short time afterwards Mr. William Archer wrote to me and told me that in a letter he had from you some days before, you had written, ‘I have read or rather spelled out a review in the Fortnightly Review by Mr. James Joyce which is very benevolent and for which I should greatly like to thank the author if only I had sufficient knowledge of the language.’ (My own knowledge of your language is not, as you see, great but I trust you will be able to decipher my meaning.) I can hardly tell you how moved I was by your message. I am a young, a very young man, and perhaps the telling of such tricks of the nerves will make you smile. But I am sure if you go back along your own life to the time when you were an undergraduate at the University as I am, and if you think what it would have meant to you to have earned a word from one who held so high a place in your esteem as you hold in mine, you will understand my feeling. One thing only I regret, namely, that an immature and hasty article should have met your eye, rather than something better and worthier of your praise. There may not have been any willful stupidity in it, but truly I can say no more. It may annoy you to have your work at the mercy of striplings but I am sure you would prefer even hotheadedness to nerveless and ‘cultured’ paradoxes.

What shall I say more? I have sounded your name defiantly through a college where it was either unknown or known faintly and darkly. I have claimed for you your rightful place in the history of the drama. I have shown what, as it seemed to me, was your highest excellence — your lofty impersonal power. Your minor claims — your satire, your technique and orchestral harmony — these, too, I advanced. Do not think me a hero-worshipper. I am not so. And when I spoke of you, in debating-societies, and so forth, I enforced attention by no futile ranting.

But we always keep the dearest things to ourselves. I did not tell them what bound me closest to you. I did not say how what I could discern dimly of your life was my pride to see, how your battles inspired me — not the obvious material battles but those that were fought and won behind your forehead — how your willful resolution to wrest the secret from life gave me heart, and how in your absolute indifference to public canons of art, friends and shibboleths you walked in the light of inward heroism. And this is what I write to you of now.

Your work on earth draws to a close and you are near the silence. It is growing dark for you. Many write of such things, but they do not know. You have only opened the way — though you have gone as far as you could upon it — to the end of ‘John Gabriel Borkman’ and its spiritual truth — for your last play stands, I take it, apart. But I am sure that higher and holier enlightenment lies — onward.

As one of the young generation for whom you have spoken I give you greeting — not humbly, because I am obscure and you in the glare, not sadly because you are an old man and I a young man, not presumptuously, nor sentimentally — but joyfully, with hope and with love, I give you greeting.

Faithfully yours,

James A. Joyce

Related Content:

James Joyce Reads From Ulysses and Finnegans Wake In His Only Two Recordings (1924/1929)

James Joyce’s “Dirty Letters” to His Wife (1909)

The Very First Reviews of James Joyce’s Ulysses: “A Work of High Genius” (1922)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It was a great pleasure to read in full for the first time Joyce’s letter to Ibsen of which I have been aware for many years.

Thank you.

Wonderful letter by young James Joyce.I had read about it earlier.However,I am glad to read the actual text.Thanks.