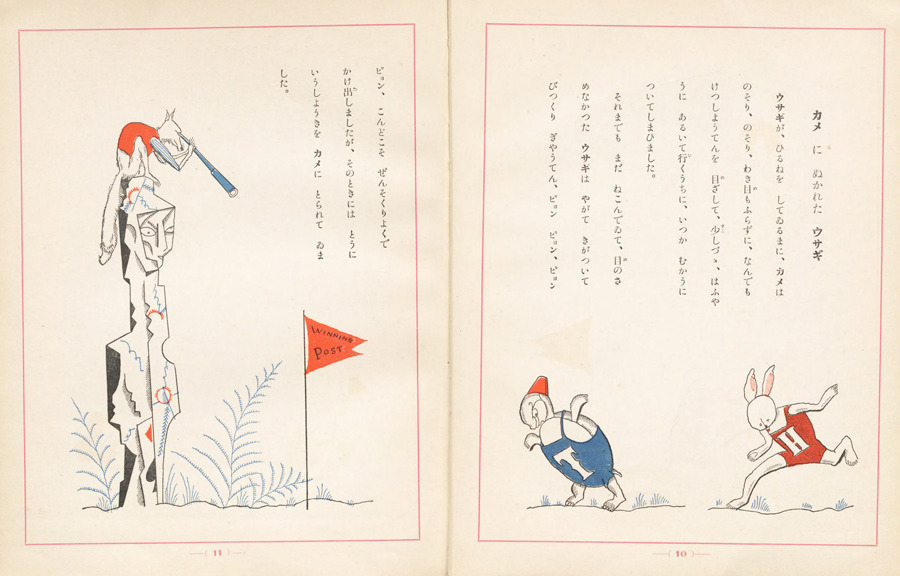

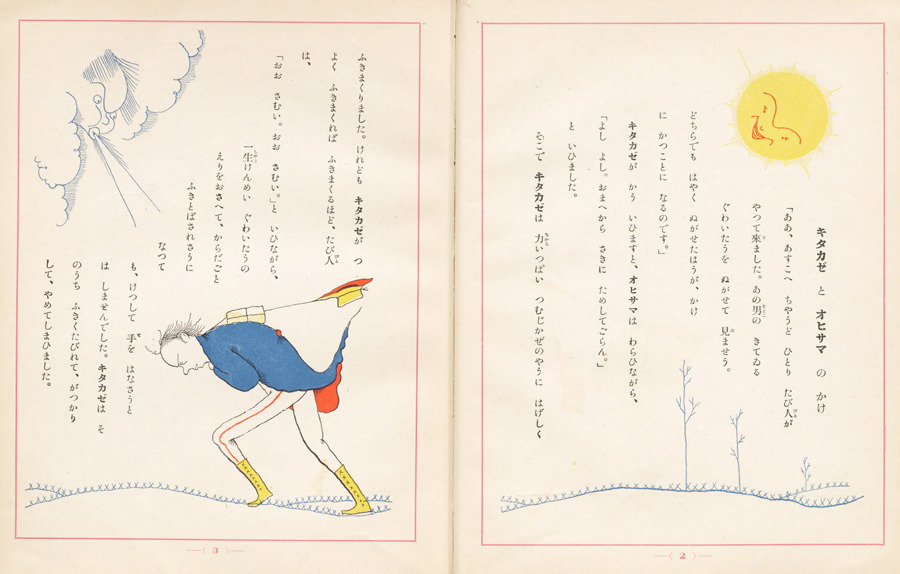

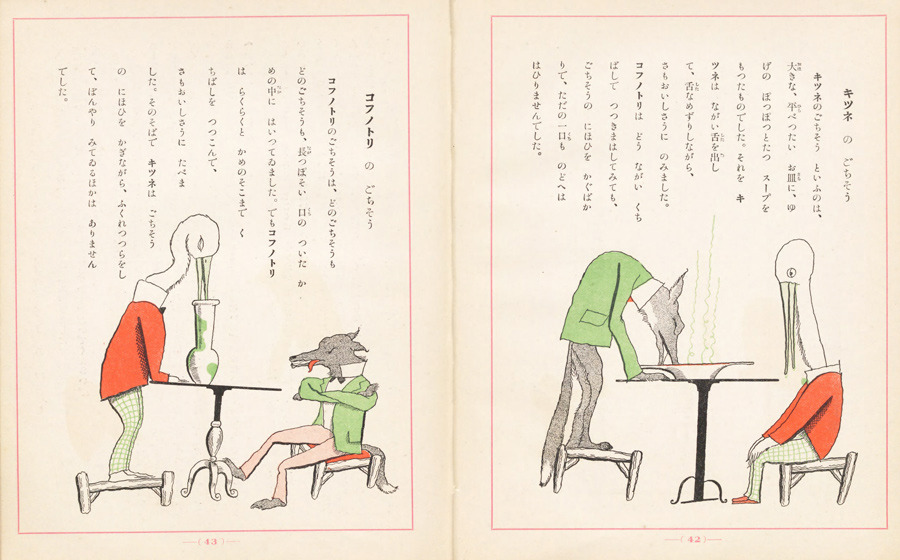

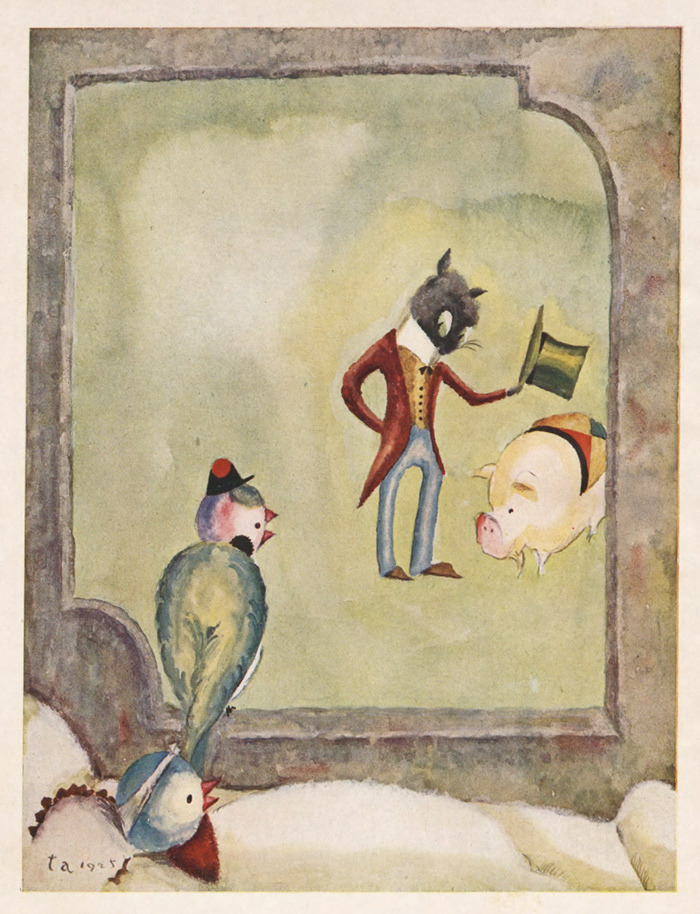

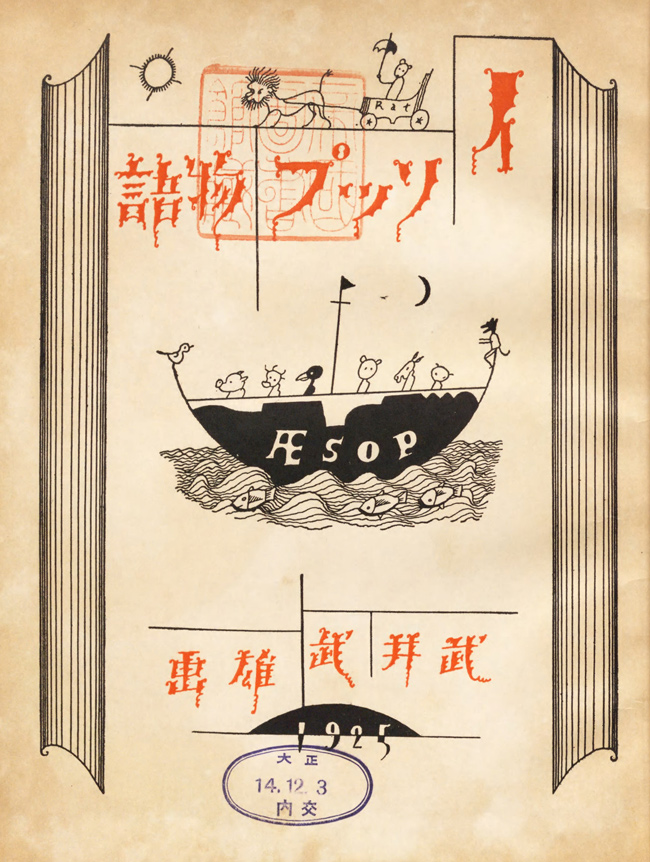

Most of us have internalized the content of a fair few of Aesop’s fables but have long since forgotten the source — if, indeed, we read it close to the source in the first place. Whether or not we’ve had any real awareness of the ancient Greek storyteller himself, we’ve certainly encountered his stories in countless much more recent interpretations over the decades. My personal favorite renditions came, skewed, in the form of the “Aesop and Son” segments on Rocky and Bullwinkle, but this 1925 Japanese edition of Aesop’s Fables, illustrated by hugely respected children’s artist Takeo Takei, must certainly rank in the same league.

Takei began his career in the early 1920s, illustrating children’s magazine covers, collections of Japanese folktales and original stories, and even youngster-oriented writings of his own. Even in that early period, he showed a professional interest in giving new aesthetic life to not just old stories but old non-Japanese stories, such as The Thousand and One Nights and Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales. It was during that time that he took on the challenge of putting his own aesthetic stamp on Aesop.

You can see quite a few of Takei’s Aesop illustrations at the book design and illustration site 50watts, whose author notes that he found the images in the database of Japan’s National Diet Library. Even if you can’t read the Japanese, you’ll know the fables in question — “The Tortoise and the Hare,” “The North Wind and the Sun,” “The Wolf and the Crane” — after nothing more than a glance at Takei’s lively artwork, which takes Aesop’s well-known characters (often animals or natural forces personified) and dresses them up in the natty style of jazz-age Tokyo high society.

Takei would go on to enjoy a long career after illustrating Aesop’s Fables. A decade after its publication, he would begin producing his best-known series of works, the “kampon” (in Japanese, “published book”). With these 138 volumes, he explored the form of the illustrated children’s book in every way he possibly could, using, according to rarebook.com, “traditional methods of letterpress, woodblock, wood engraving, stencil, etching and lithography,” as well as clay block-prints and “definitely non-traditional images of woven labels, painted glass, ceramic, and cello-slides — transparencies composed of bright cellophane paper.” He would continue working working right up until his death in 1983, leaving a legacy of influence on Japanese visual culture as deep as the one Aesop left on storytelling.

via 50watts

Related Content:

Early Japanese Animations: The Origins of Anime (1917–1931)

Advertisements from Japan’s Golden Age of Art Deco

Glorious Early 20th-Century Japanese Ads for Beer, Smokes & Sake (1902–1954)

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply