It does seem possible, I think, to overvalue the significance of a writer’s library to his or her own literary productions. We all hold on to books that have long since ceased to have any pull on us, and lose track of books that have greatly influenced us. What we keep or don’t keep can be as much a matter of happenstance or sentiment as deliberate personal archiving. But while we may not always be conscious curators of our lives’ effects, those effects still speak for us when we are gone in ways we may never have intended. In the case of famous—and famously controversial—thinkers like Hannah Arendt, what is left behind will always constitute a body of evidence. And in some cases—such as that of Arendt’s teacher and onetime lover Martin Heidegger’s glaringly anti-Semitic Black Notebooks—the evidence can be irrevocably damning.

In Arendt’s case, we have no such smoking gun to substantiate arguments that, despite her own background, Arendt was anti-Jewish and blamed the victims of the Holocaust. During the so-called “Eichmann wars” in the mid-twentieth century, a torrent of criticism bombarded Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, the compilation of dispatches she penned as an observer of the Nazi arch-bureaucrat’s trial. These days, writes Corey Robin in The Nation, “while the controversy over Eichmann remains, the controversialists have moved on.” The debate now seems more centered on Arendt’s book itself than on her motivations. What do Arendt’s observations reveal to us today about the logic of totalitarianism and genocidal state actions? One way to approach the questions of meaning in Eichmann, and in her monumental The Origins of Totalitarianism, is to examine the sources of her thought—and her use of those sources.

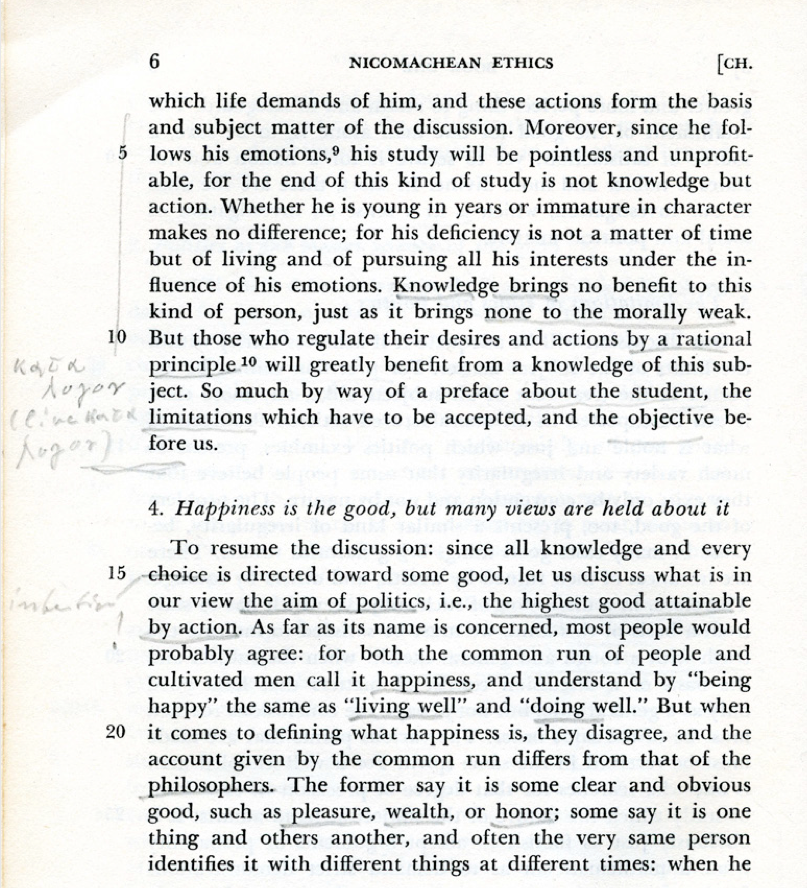

Arendt’s library—much of it on view online thanks to Bard college—offers us a unique opportunity to do just that, not only by giving us access to the specific editions and translations that she herself read and saved (for whatever reason), but also by offering insight into what Arendt considered important enough in those texts to underline and annotate. In Bard’s digital collection of “Arendt Marginalia”—selections of her annotated books in downloadable PDFs—we see a political philosophy informed by Aristotle (see a page from her copy of Nicomachean Ethics above), Plato, and Kant, but also by conservative German political theorist Carl Schmitt, a member and active supporter of Nazism, and of course, by Heidegger, whose work occupies a central place in her library: in German and English (like his Early Greek Thinking above, inscribed by the translator), and in primary and secondary sources.

While it may go too far to claim, as prominent scholar Bernard Wasserstein did in 2009, that an examination of Arendt’s sources shows her internalizing the values of Nazis and anti-Semites, the preponderance of conservative German thinkers in her personal library does give us a sense of her intellectual leanings. But we cannot draw broad conclusions from a cursory survey of a lifetime of reading and re-reading, though we do see a particularly Aristotelian strain in her thinking: that the individual is only as healthy as his or her political culture. What scholars of Arendt will find in Bard’s digital collection are ample clues to the development and evolution of her philosophy over time. What lay readers will find is the outline of a course on the sources of Arendt-ian thought, including not only Greeks and Germans, but the American poet Robert Lowell, who wrote a glowing profile of Arendt and contributed at least four signed books of his to her library.

I say “at least” because the Bard digital collection is yet incomplete, representing only a portion of the physical media in the college’s physical archive of “approximately 4,000 volumes, ephemera and pamphlets that made up the library in Hannah Arendt’s last apartment in New York City.” What we don’t have online are books inscribed to her by Jewish scholar and mystic Gershom Scholem, by W.H. Auden and Randall Jarrell, and many others. Nonetheless the “Arendt Marginalia” gives us an opportunity to peer into a writer and scholar’s process, and see her wrestle with the thought of her predecessors and contemporaries. The full Arendt collection gives us even more to sift through, including private correspondence and recordings of public speeches. The digitization of these sources offers many opportunities for those who cannot travel to New York and access the physical archives to delve into Arendt’s intellectual world in ways previously only available to professional academics.

Related Contents:

Hannah Arendt Discusses Philosophy, Politics & Eichmann in Rare 1964 TV Interview

Hannah Arendt’s Original Articles on “the Banality of Evil” in the New Yorker Archive

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply