Most of us strive to achieve some kind of distinction—or competence—in one, often quite narrow, field. And for some of us, the path to success involves leaving behind many a path not taken. Childhood pursuits like ballet, for example, the high jump, the trumpet, acting, etc. become hazy memories of former selves as we grow older and busier. But if you have the formidable will and intellect of émigré Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov, you see no need to abandon your beloved avocations simply because you are one of the 20th century’s most celebrated writers—in both Russian and English. No indeed. You also go on to become a celebrated amateur lepidopterist (see his butterfly drawings here), earning distinction as curator of lepidoptera at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and originator of an evolutionary theory of butterfly migration. And as if that were not enough, you spend your spare time formulating complicated chess problems, earning such a reputation that you are invited in 1970 to join the American chess team to create problems for international competitions.

Nabokov was not easily impressed by other writers or scientists, but he held chess players in especially high regard. His “heroes include a chess grandmaster,” writes Nabokov scholar Janet Gezari, “and a chess problem composer…; chess games occur in several of the novels; and chess and chess problem language and imagery regularly put his readers’ chess knowledge to the test.” His third novel, 1930’s The Defense, centers on a chess master driven to despair by his genius, a character based on real grandmaster Curt von Bardeleben. For Nabokov, the skill and ingenuity required for composing chess problems paralleled that required for great writing: “The strain on the mind is formidable,” he wrote in his memoir Speak, Memory, “the element of time drops out of one’s consciousness.” Puzzling out chess problems and solutions, he wrote, “demand from the composer the same virtues that characterize all worthwhile art: originality, invention, conciseness, harmony, complexity and splendid insincerity”—all qualities, we’d have to agree, of Nabokov’s finely wrought fictions.

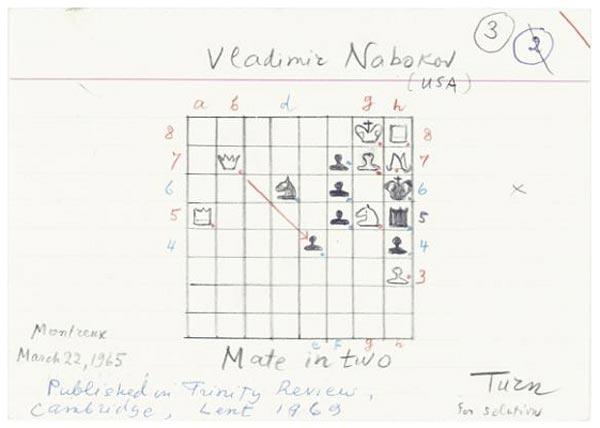

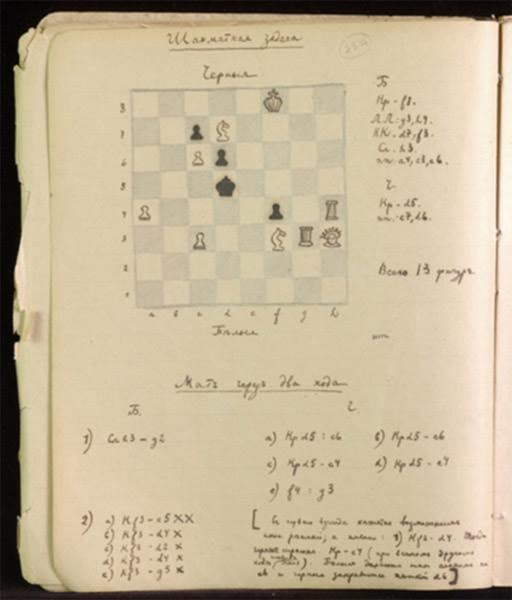

In 1970, Nabokov published Poems and Problems, a collection of thirty-nine Russian poems, with English translations, fourteen English poems, and eighteen chess problems, with solutions. He had pursued this passion since his teens, and published nearly three dozen chess problems in his lifetime. At the top of the post, see one of them, “Mate in 2,” sketched out in Nabokov’s hand (try to solve it yourself here). Below it, see another of the author’s chess problem sketches, and in the photo above, see Nabokov absorbed in a chess game with his wife.

Though it may seem that Nabokov had limitless energy and time to devote to his extra-literary pursuits, he also wrote with regret about the price he paid for his obsession: “the possessive haunting of my mind,” as he called it, “with carved pieces or their intellectual counterparts swallowed up so much time during my most productive and fruitful years, time which I could have better spent on linguistic adventures.” Like the lepidopterists still marveling over Nabokov’s contributions to that field, the chess lovers who encounter his problems, and his ingenious use of the game in fiction, would hardly agree that his pursuit of chess was fruitless or unproductive.

Related Content:

Vladimir Nabokov’s Delightful Butterfly Drawings

Vladimir Nabokov Creates a Hand-Drawn Map of James Joyce’s Ulysses

Vladimir Nabokov Names the Greatest (and Most Overrated) Novels of the 20th Century

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A really interesting article about the life of a writer and very inspirational (at least for me) about how you never have to stop doing the things you love. We all can do all the thing we want, there is no excuses.

Chess compositions by Vladimir V. Nabokov accumulated so far are at website Yet Another Chess Problem Database (Yacpdb). In the “Author” box type last name first; thereafter, hit the “Search” tab.

One of the best comments I’ve Ever Read !