Image courtesy of 2001Italia

Origin stories are all the rage these days given the ubiquity of superhero films and television series. But for all their smash-em-up spectacle and breakneck pacing, they generally feel overstuffed and disposable. As with the Age of Ultron, there is an age, every summer, of some Marvel or DC hero or other. Or all of them at once, at this point, in a perpetual onslaught. On the other hand, we still have the quietly ominous, thoughtful science fiction film, the offspring of Nicolas Roeg and Andrei Tarkovsky, in movies like Ex Machina. These come and go, some better than others, but also always with us. Different as these two types of films can be, in style and tone, neither would likely look and feel the way they do without Stanley Kubrick’s intensely introspective and profoundly epic 2001: A Space Odyssey.

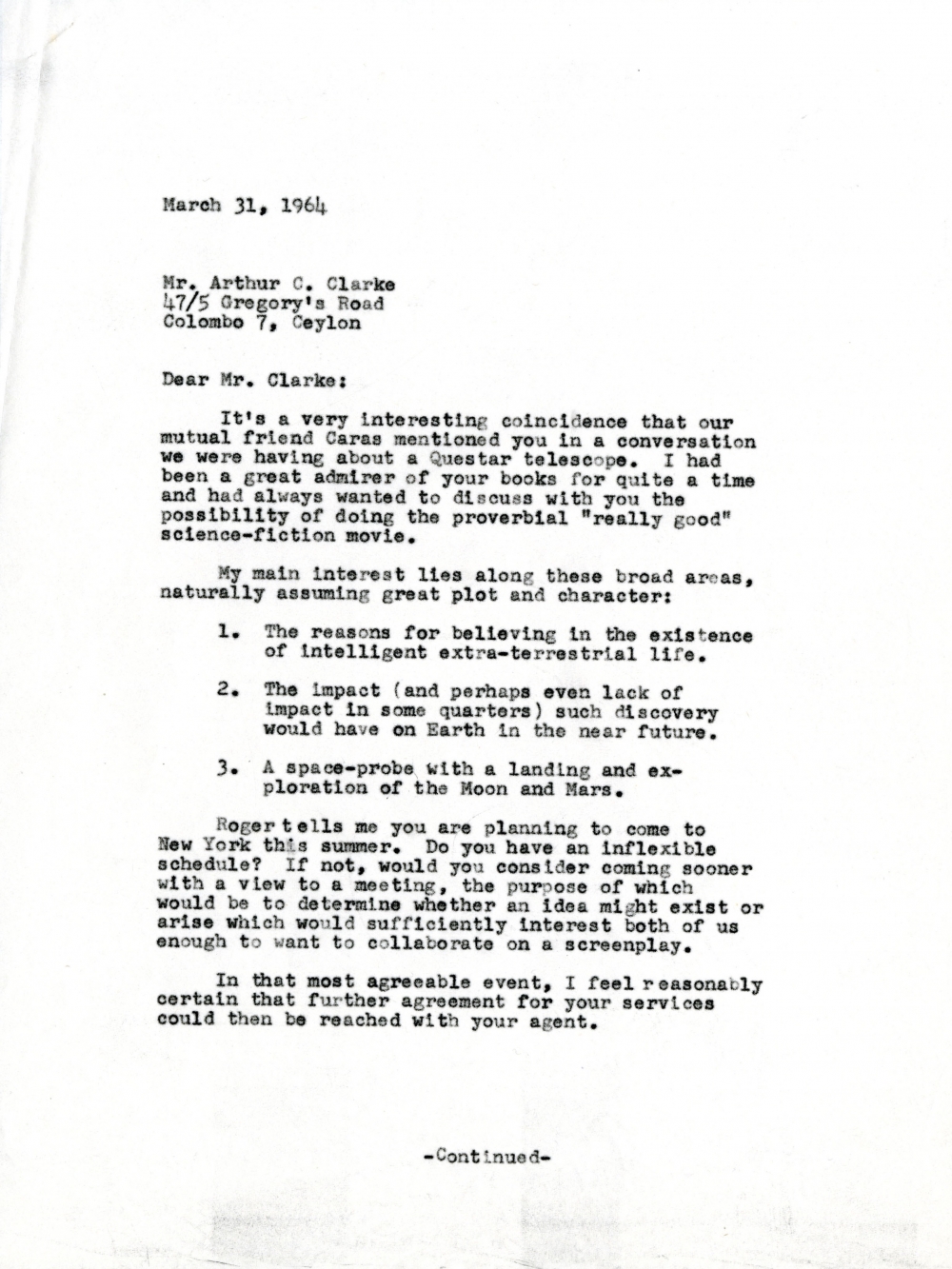

The origin story of this incredible 1968 film begins on March 31, 1964 when Kubrick wrote the letter below to Arthur C. Clarke, proposing that the two collaborate on “the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction film.” “I had been a great admirer of your books for quite a time,” writes Kubrick, and gives Clarke three “broad areas” of interest, “naturally assuming great plot and character.” Naturally.

“Clarke’s response,” writes BFI, “was immediately enthusiastic, expressing a mutual admiration.” Kubrick, Clarke told their mutual friend Roger Caras, “is obviously an astonishing man.” In his response to the director himself, Clarke wrote on April 8, ““For my part, I am absolutely dying to see Dr. Strangelove; Lolita is one of the few films I have seen twice – the first time to enjoy it, the second time to see how it was done.” The two met in New York and talked for hours, and from Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel of Eternity” was born perhaps the best “really good” science fiction film ever made.

Clarke would compare the differences between the story and the film to those between an acorn and an oak tree, according to Italian Kubrick site 2001Italia. After that meeting, the two would spend almost four years writing the screenplay together and envisioning the harrowing voyage to Jupiter that ends so tragically—and strangely—for the two astronauts left to experience it. It’s a collaborative success Kubrick clearly foresaw when he approached Clarke, but in his letter, above, with transcript below—courtesy of Letters of Note—he plays it cool, using the pretext of a telescope Clarke owned to slip in discussion about the film project. We are almost led to believe,” writes 2001Italia, “that the movie was an excuse” to discuss the gadget. But of course we know better.

Dear Mr Clarke:

It’s a very interesting coincidence that our mutual friend Caras mentioned you in a conversation we were having about a Questar telescope. I had been a great admirer of your books for quite a time and had always wanted to discuss with you the possibility of doing the proverbial “really good” science-fiction movie.

My main interest lies along these broad areas, naturally assuming great plot and character:

- The reasons for believing in the existence of intelligent extra-terrestrial life.

- The impact (and perhaps even lack of impact in some quarters) such discovery would have on Earth in the near future.

- A space probe with a landing and exploration of the Moon and Mars.

Roger [Caras ]tells me you are planning to come to New York this summer. Do you have an inflexible schedule? If not, would you consider coming sooner with a view to a meeting, the purpose of which would be to determine whether an idea might exist or arise which could sufficiently interest both of us enough to want to collaborate on a screenplay?

Incidentally, “Sky & Telescope” advertise a number of scopes. If one has the room for a medium size scope on a pedestal, say the size of a camera tripod, is there any particular model in a class by itself, as the Questar is for small portable scopes?

Best regards,

Kubrick pursued his projects very deliberately and passionately, motivated by great personal interest. Though his films can feel detached and cold, and he himself seems like a very aloof character, the opposite was true, according to those who knew him best. Below, see a short video from The University of the Arts London’s Stanley Kubrick Archive profiling the way Kubrick went about choosing his films, best summed up by Jan Harlon, Kubrick’s brother-in-law and producer: “No love, no quality, and in Stanley’s case, no love, no film.”

Related Content:

Stanley Kubrick’s Annotated Copy of Stephen King’s The Shining

Stanley Kubrick’s Rare 1965 Interview with The New Yorker

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It is interesting to see that according to the letter his ‘main interests’ were actually so uninspiring. Well, at least initially. Maybe he changed his mind later? Arguably, what makes the Odyssey great is its undoubtedly Nietzschean framework. Basically, the movie is a rip-off – or more likely a homage – to “Also sprach Zarathustra”, cover to cover. Nietzsche wrote his books at the time when the discovery of the discovery of the vastness of outer space was very acutely felt in the culture — that one has to keep in mind while reading him. The remainder of the Odyssey, the generic sci-fi bits, that is, is more of a filler for the sci-fi audience in the cinemas than the real content. Or so it seems to me. You are free to disagree, however.

I don’t get it. How did this pave the way for Bladerunner?

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/gerry-flahive/stanley-kubrick-science_b_5176656.html