Charles Guiteau, the man who assassinated James Garfield, tried to argue in court that he just shot the president — the doctors actually killed him. Though Guiteau was ultimately hanged for his crime in 1882, he did have a point. Garfield’s doctor, William Bliss, jammed his unsterilized fingers in the presidential wound in an attempt to pull out the bullet. So did a host of other specialists. President Garfield died 80 days later of, among other things, sepsis. It was later concluded that the president would have likely survived if the doctors had kept their hands to themselves.

Garfield’s death was one of the catalysts that helped popularize Joseph Lister’s ideas about bacteria, a concept that vastly improved the quality of medical care. A hundred years later, for example, Ronald Reagan suffered from almost an identical bullet wound and was back to work within weeks.

In the 19th century and centuries before, diseases weren’t well understood and death was mysterious and divine. In the evangelical revivals of the mid-19th century, the end of life was seen as something to embrace. After all, God was calling his believers back home. Then with a growing understanding of germs, that sense of wonder with our mortality changed. “God hadn’t called the individual to him,” writes Deborah Lutz, scholar of Victorian culture, in The New York Times this week. “Rather, a malady had overtaken the body. Rather than dying at home, the sick were carted off to hospitals.” Death, in other words, became divorced from everyday life.

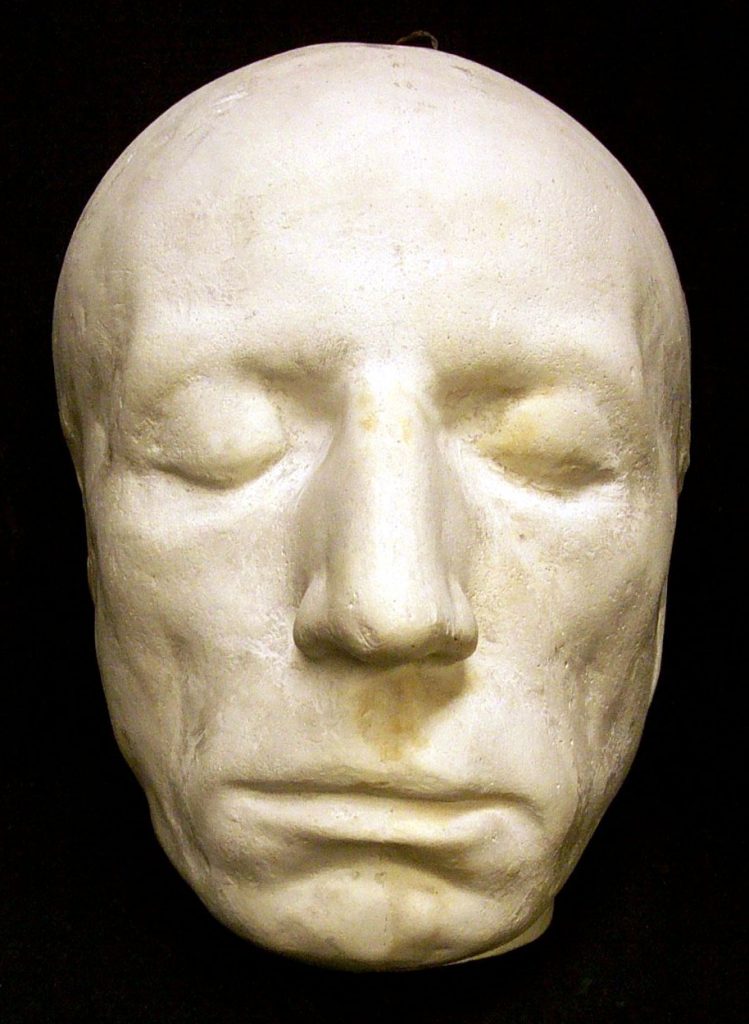

So from our 21st century viewpoint, the Victorians’ (and their predecessors’) tendency to collect mementos of the dead, like death masks, might seem gruesome. But from their point of view, our panicked denial of death would probably seem foolish and perverse. Mortality, after all, is a fact of life.

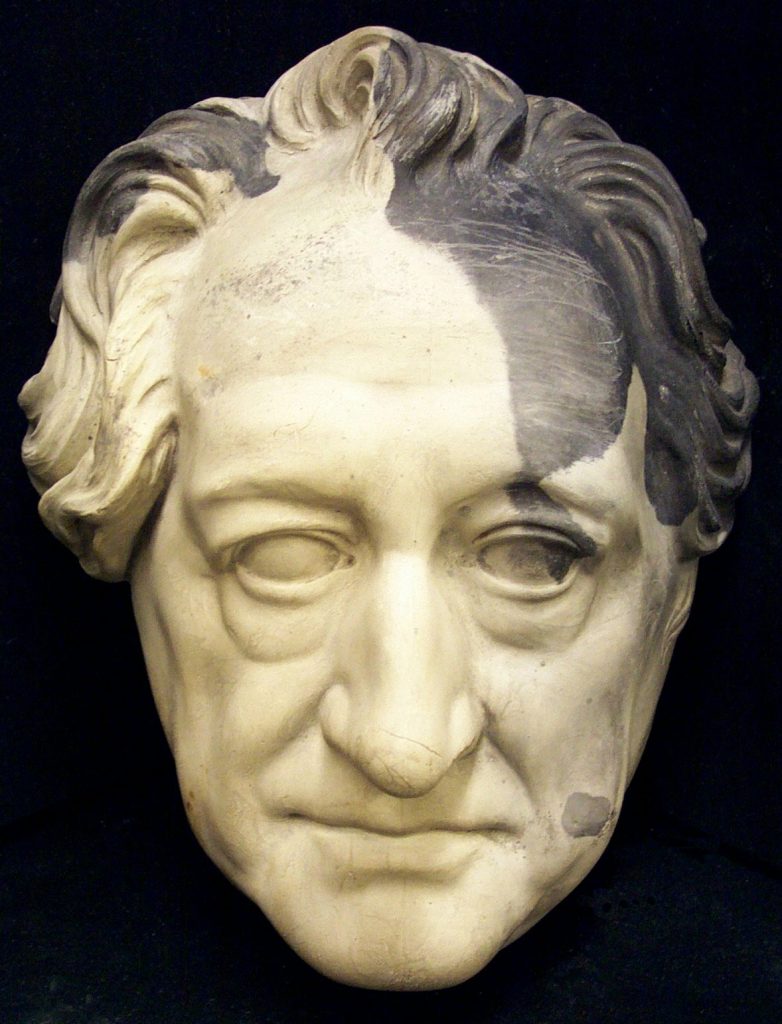

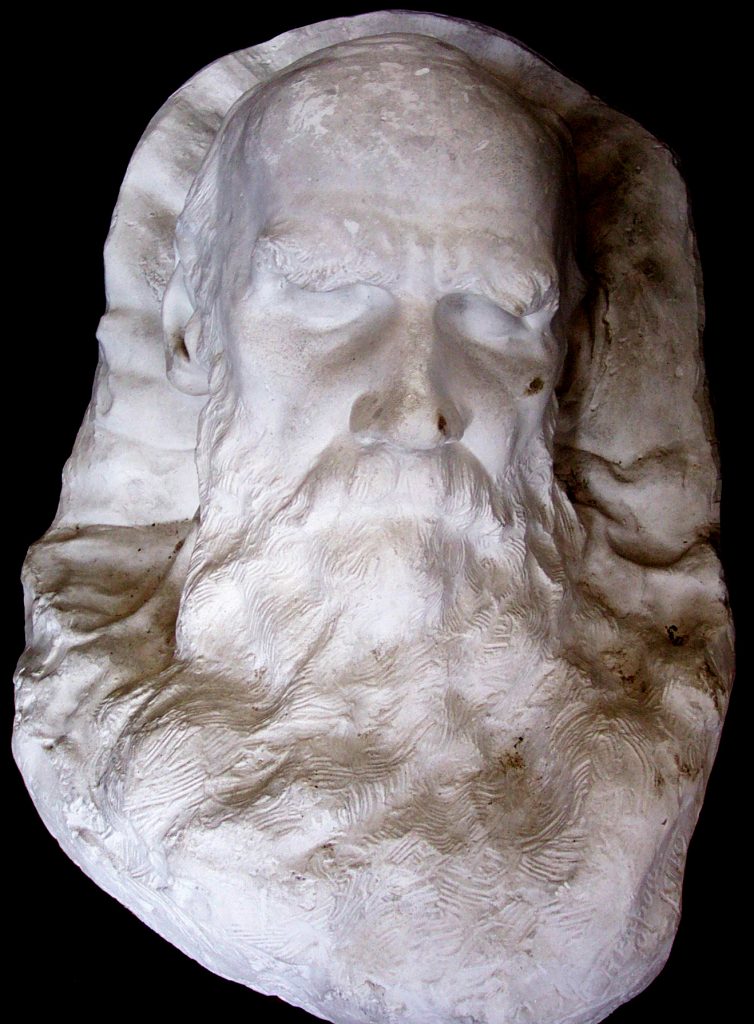

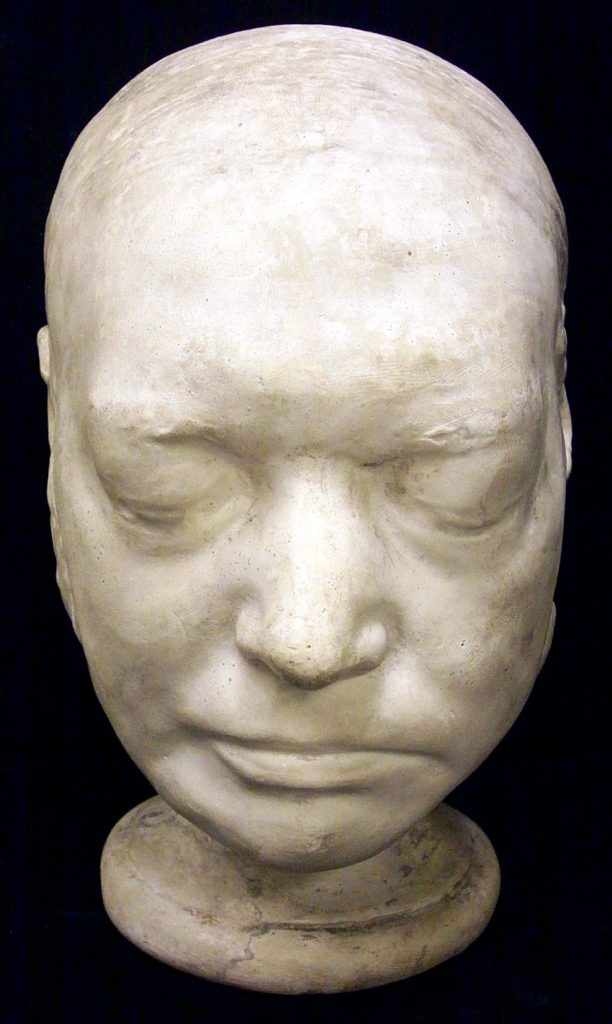

Princeton University’s Laurence Hutton Collection has dozens of death masks of famous politicians, philosophers and authors. People like Isaac Newton, Abraham Lincoln and Leo Tolstoy. There’s something humbling about seeing these titans of Western culture captured at such an intimate moment. Stripped of all the markers of class and rank, they look like people you might see on the street.

Aside from a rather unconvincing effigy of Queen Elizabeth, the collection features few masks of great women. No Jane Austens or Emily Dickinsons here. The collection also, sadly, lacks a mask of James Garfield.

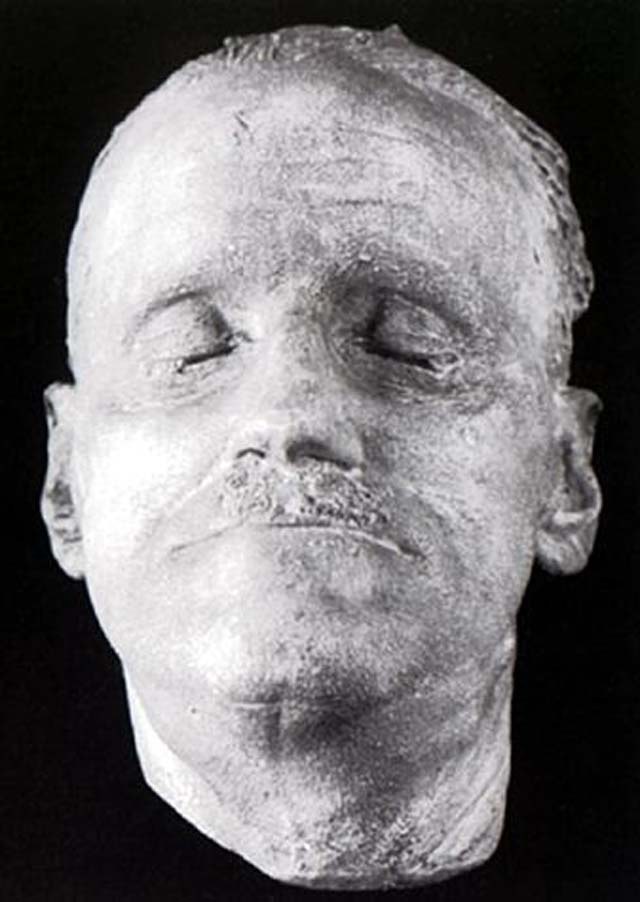

Above you can find death masks of literary figures from the 14th to early 20th centuries. From top to bottom, you will see James Joyce, Goethe, Leo Tolstoy, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Dante and William Wordsworth.

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads.

Here is President Garfield’s death mask. I’ve see it in person and the lighting makes it more eerie than in this photo. https://garfieldnps.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/the-president-james-a-garfield-death-mask/

facts like conditions can change

Thanks for very helpfully identifying the men behind the masks…

I haven’t seen Tolstoy since a dinner before his death and, having grown elderly, I forget what he looked like. Please identify each author’s death mask. Thank you.

Dear Sirs,

the article is inaccurate. According to scientific and medical researches that took place in 2007, the mask depicting Goethe is not a death mask, but a copy of a mask created in 1807, when Goethe was 58 and very much alive.

Source: http://www.welt.de/kultur/article877480/So-sah-Goethe-wirklich-aus.html

Hi Iona, you hover your mouse over the picture, a link will appear that contains the name for each picture.