The science of argumentation can seem complicated, but in day-to-day terms, it quite often comes down to competing emotions. Political disagreements thrive on disgust and fear; we shut down our reasoning when we feel stressed or angry; and it is difficult to get opponents to hear us, whether they agree or not, if we do not exhibit any sympathy for their position, hard as that may be.

However, subjects in tests told not to feel anything about an issue before viewing media about it tend to be more supportive. They’ve had some opportunity to access higher order thinking skills and to override knee-jerk reactions. Most arguments take place in the fray—family dinners, online forum wars—but even in these cases, applying the best of our reasoning, before, during, or after, can put us in better stead. As Ali Almossawi, author of An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments (read online version here) puts it in his preface:

… formalizing one’s reasoning [can] lead to useful benefits such as clarity of thought and expression, objectivity and greater confidence. The ability to analyze arguments also help[s] provide a yardstick for knowing when to withdraw from discussions that would most likely be futile.

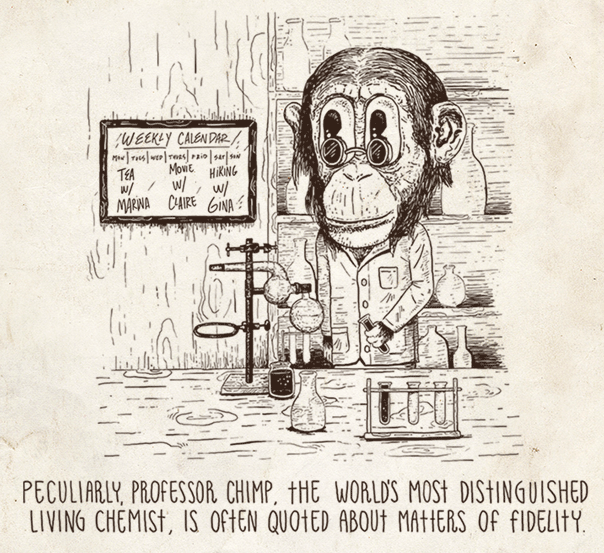

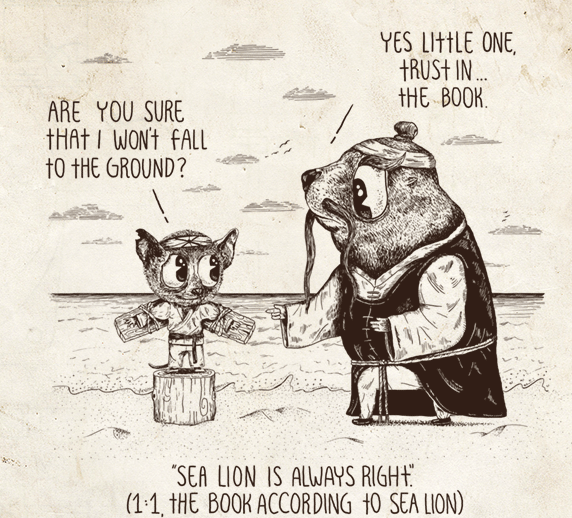

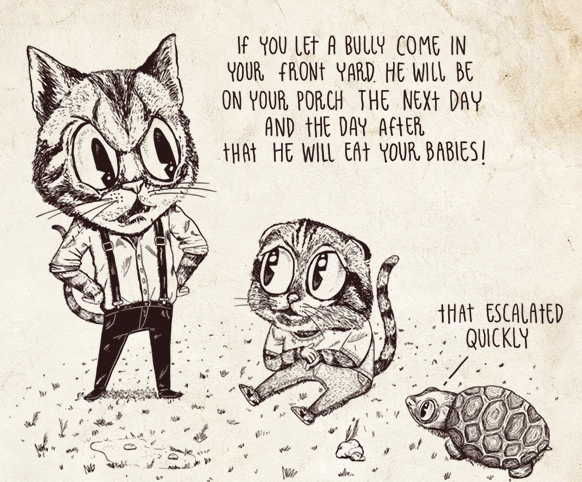

Almossawi’s strategy to mitigate bad, or wasted, thinking comes in the form of an inoculation. He quotes Stephen King, who “describes his experience of reading a particularly terrible novel as, ‘the literary equivalent of a smallpox vaccination.’” Rather than a Ciceronian treatise on what makes a good argument, Almossawi presents us with nineteen examples of the bad: informal logical fallacies we may be familiar with—Appeal to Authority (below), Circular Reasoning (further down), Slippery Slope (bottom)—as well as many we may not be.

The twist here is in Alejandro Giraldo’s playful illustrations, and the memorable examples that follow Almossawi’s descriptions. Inspired partly by “allegories such as Orwell’s Animal Farm and partly by the humorous nonsense of works such as Lewis Carroll’s stories and poems,” the drawings are also highly reminiscent, if not very much inspired by, the baroque cartoons of Tony Millionaire. The art is rich and full of surprises; the sample arguments silly but effective at making the point.

The next time you find yourself melting down over a disagreement, it will likely help to take a time out and refresh yourself with this useful primer. If nothing else, it will give you some insight into the shortcomings of your own arguments, and maybe some measure of when to drop the subject altogether. As Richard Feynman—quoted in an epilogue to the book—once remarked, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” Find the book online here, or purchase a copy here.

Related Content:

130+ Free Online Philosophy Courses

Philosopher Daniel Dennett Presents Seven Tools For Critical Thinking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply