Akira Kurosawa, “the Emperor” of Japanese film, made movies — and in some sense, he never wasn’t making movies. Even when he lacked the resources to actually shoot them, he prepared to make movies in the future, thinking through their every detail. Critic and historian of Japanese cinema Donald Richie’s remembrance of the director who did more than anyone to define the Japanese film emphasizes Kurosawa’s “concern for perfecting the product” — to put it mildly. “Though many film companies would have been delighted by such directorial devotion,” Richie writes, “Japanese studios are commonly more impressed by cooperation than by innovation.”

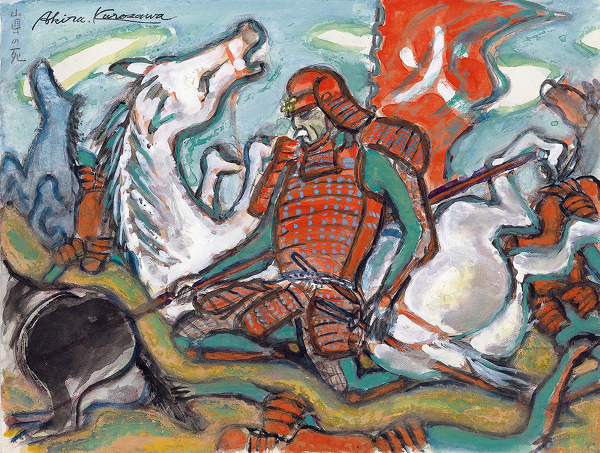

Kurosawa thus found it more and more difficult, as his career went on, to raise money for his ambitious projects. Richie recalls a time in the 1970s when, “convinced that Kagemusha would never get made, Kurosawa spent his time painting pictures of every scene — this collection would have to take the place of the unrealized film. He had, like many other directors, long used storyboards. These now blossomed into whole galleries — screening rooms for unmade masterpieces.” When he couldn’t shoot movies, he wrote them. If he’d written all he could, he painted them.

At Flavorwire, you can see a comparison between Kurosawa’s paintings and the frames of his movies. “He hand-crafted these images in order to convey his enthusiasm for the project,” writes Alison Nastasi, going on to quote the director’s own autobiography: “My purpose was not to paint well. I made free use of various materials that happened to be at hand.”

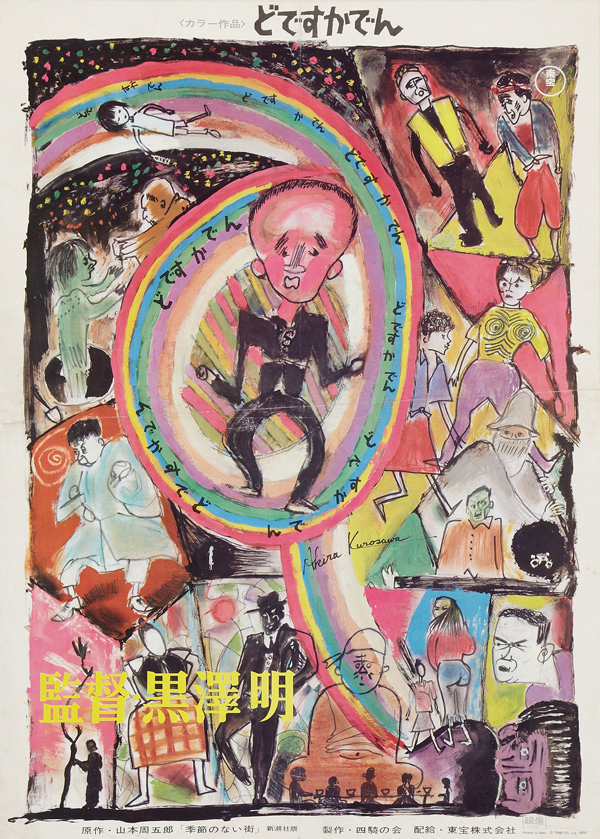

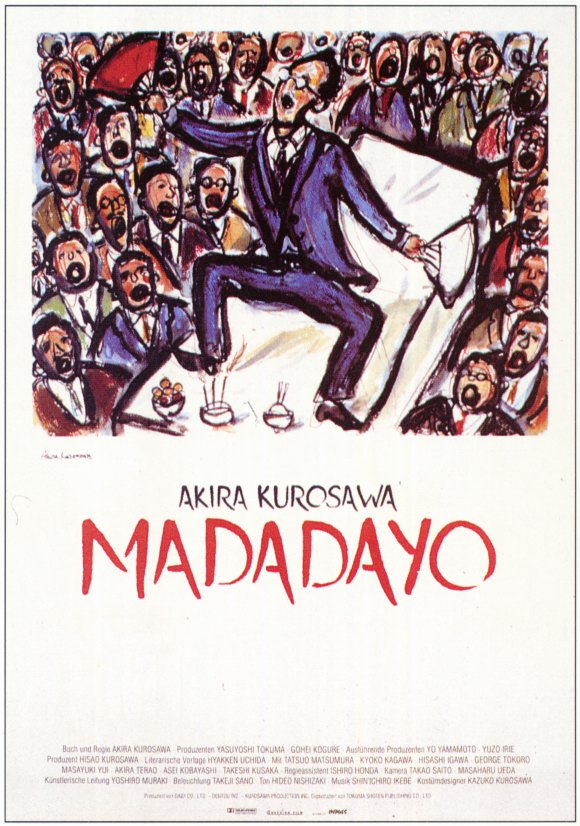

But as you can see, the Emperor knew what he wanted; the actual shots clearly represent a realization of what he’d devoted so much time and energy to visualizing beforehand. Occasionally, Kurosawa’s own artwork even made it to his movies’ official posters, especially lesser-known (whatever “lesser-known” means in the context of the Kurosawa canon) personal works like 1970’s Dodes’ka-den and 1993’s Madadayo.

We might chalk up the filmmaker’s interest in painting — and perhaps in filmmaking — in large part to his older brother Heigo, with whom he gazed upon the aftermath of Tokyo’s 1923 Kantō earthquake. A live silent film narrator and aspiring painter in the Proletarian Artists’ League, Heigo committed suicide in 1933 after his political disillusionment and the career-killing introduction of sound film. Young Akira would make his directorial debut a decade later and, in the 55 years that followed, presumably do Heigo proud on every possible level.

A catalog including 40 vivid, large, full-color drawings by Kurosawa was published in 1994 to accompany an exhibition in New York.

Related Content:

Akira Kurosawa’s 80-Minute Master Class on Making “Beautiful Movies” (2000)

Akira Kurosawa’s List of His 100 Favorite Movies

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Great article!

How much around is an original Akira Kurosawa painting/storyboard worth?