It’s easy to think we know all there is to know about Sigmund Freud. His name, after all, has become an adjective, a sure sign that someone’s legacy has embedded itself in the cultural consciousness. But did you know that the German neurologist we credit with the invention of psychoanalysis, the diagnoses of hysteria, dream interpretation, and the death drive began his career patiently dissecting eels in search of… eel testicles? Perhaps you did know that. Perhaps you only suspected it. There are few things about Freud—who also pioneered both the medical and recreational use of cocaine, joined the august British Royal Society, and unwittingly re-engineered philosophy and literary criticism—that surprise me anymore. Freud was a peculiarly talented individual.

One area in which he excelled may seem modest next to his roster of publications and celebrity acquaintances, and yet, the doctor’s skill as a medical draughtsman and maker of diagrams to illustrate his theories surely deserves some appreciation. Freud’s drawing received a book length treatment in 2006’s From Neurology to Psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud’s Neurological Drawings and Diagrams of the Mind by Lynn Gamwell and Mark Solms. These are but a small sampling of the many works of medical art found within its covers, taken from a 2006 exhibit at the New York Academy of Medicine of the largest collection of Freud’s drawings ever assembled, in commemoration of his 150th birthday.

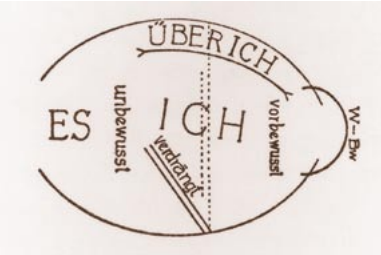

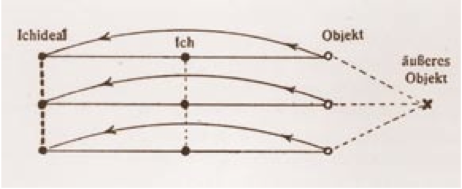

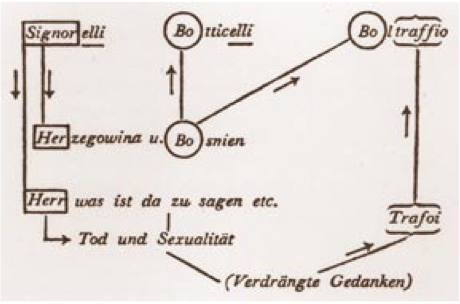

As the title of the book indicates, the drawings literally illustrate the radical shift Freud made from the hard science of neurology to a practice of his own invention. Curator Gamwell writes, “as Freud focused on increasingly complex mental functions such as disorders of language and memory, he put aside any attempt to diagram the underlying physiological structure, such as neurological pathways, and he began making schematic images of hypothetical psychological structures,” i.e. the Ego, Superego, and Id, as represented at the top in a 1933 diagram. Below it, from 1921, see “Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego,” a schematic that “attempts to represent relations between the major mental systems (or agencies) in a group of human minds.” And just above, see Freud’s diagram for “The Psychical Mechanism of Forgetfulness” from 1898, depicting “associative links between various conscious, preconscious and unconscious word presentations.”

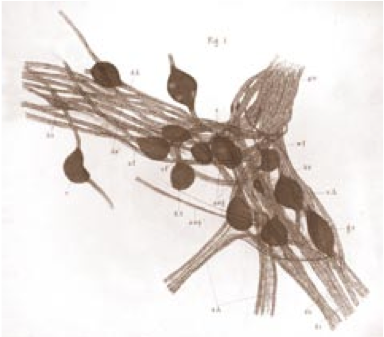

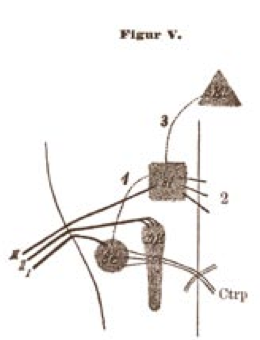

It is in these late nineteenth-century diagrams that we see Freud make the definitive move from empirically observed illustrations of physical structures—like the 1878 “Spinal Ganglia and Spinal Chord of Petromyzom” above—to relations between ideas and “conceptual entities that have no tangible existence in the physical world.” That shift, generally marked by the publication of Studies in Hysteria in 1895, caused Freud some unease. “Looking back over his career 30 years later,” writes Mark Solms, “ his longing for the comfortable respectability of his earlier career is still evident.” Even at the time, Freud would write in Studies in Hysteria that his case histories “lack the serious stamp of science.” Though his studies of eel, lamprey, and human brains involved tangible, observable phenomena, he approached the new discipline of psychoanalysis with no less rigor, stating only that the “the nature of the subject” had changed, not his method.

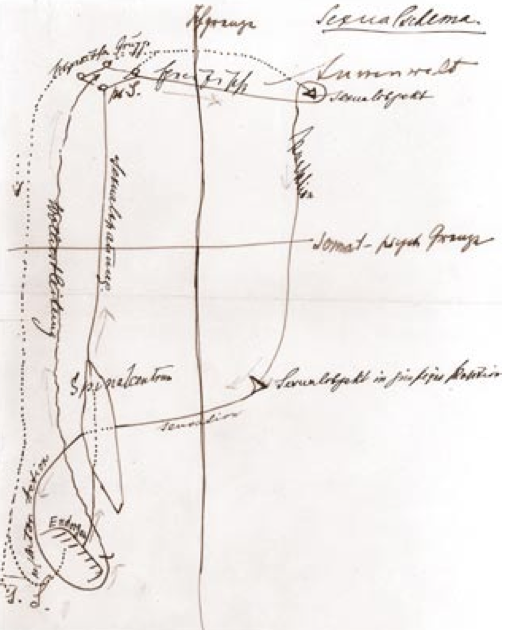

The drawings, writes Benedict Carey in the New York Times, “tell a story in three acts, from biology to psychology, from the microscope to the couch.” As Freud makes the transition, his meticulously detailed medical work, copied from glass slides, gives way to loose outlines. One drawing of the brain’s auditory system from 1886 (above) “is as spare and geometric as a Calder sculpture.” Just a few years later, Freud sketched out the diagram below in 1894, a schematic, writes Solms, of “the relationship between various normal and pathological mood states and sexual physiology.” It’s his first purely psychoanalytic drawing, sketched in a letter to a colleague, Dr. Wilhelm Fleiss.

In the later diagrams, as we see above, his tentative freehand gave way to typescript and a technical draughtsman’s precision, with some drawings resembling, in Carey’s words, “the schematic for an air-conditioning system.” Freud seems to comment on the architectural nature of these diagrams when he writes in The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900, “We are justified, in my view, in giving free reign to our speculations so long as we retain the coolness of our judgment, and do not mistake the scaffolding for the building.” It’s a warning many of Freud’s disciples may not have heeded carefully enough.

Related Content:

How a Young Sigmund Freud Researched & Got Addicted to Cocaine, the New “Miracle Drug,” in 1894

Sigmund Freud Appears in Rare, Surviving Video & Audio Recorded During the 1930s

Free Online Psychology Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

One more proof Freud was addicted to cocaine every moment of his adult life.

Federal welfare programs add up to a solid one trillion dollars of wasted spending each year. The war on poverty is a complete failure. We need to forget Freud and his evil legacy. We need active church attendance. When the pilgrims came here they solved all of their social problems with a 10% tithe (voluntary) and three visits to the church each week. Where are we now?

Yeah, I guess drowning people to see if they float or not and burning witches doesn’t cost much.