The recent “adjunct walk out day” has reminded people outside academia—at least those who paid any attention—of the decaying state of American higher education, a condition driven in part by a searing undercurrent of anti-intellectualism in U.S. political culture. It’s a trend historian Richard Hofstadter identified last century in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1963 study Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. But not long after Hofstadter’s book appeared, another, more vital current took hold in the 60s and 70s, one brought on by the broadening possibilities for those previously denied access to elite universities, and by reciprocal relationships between radicals and scholars. Academics like Timothy Leary became figureheads of the counterculture, revolutionaries like Huey Newton earned Ph.D.s, and activist professors like Angela Davis held the line between the worlds of higher ed and popular dissent. The universities became not only sites of student protest, but also matrices of revolutionary theory.

Into this fomenting intellectual culture stepped French theorist Michel Foucault, who first lectured in the U.S. in 1975 after the publication of his History of Sexuality. Foucault was a true product of the French university system and an academic superstar of sorts, as well as a gadfly of revolutionary movements from Paris in ’68, to Iran in ’79, to Berkeley in the 80s. His work as a philosopher and political dissident prompted one biographer to refer to him as a “militant intellectual,” though his politics could sometimes be as obscure as his prose. By 1981, he had risen to such cultural prominence in the States that Time magazine published a profile of him and his “growing cult.” One of Foucault’s American acolytes, Simeon Wade, befriended the philosopher in the mid-seventies and wrote an unpublished, 121-page account of Foucault’s alleged 1975 LSD trip in Death Valley (referred to in James Miller’s The Passion of Michel Foucault). Wade, along with a number of other University of California students, also interviewed Foucault the following year.

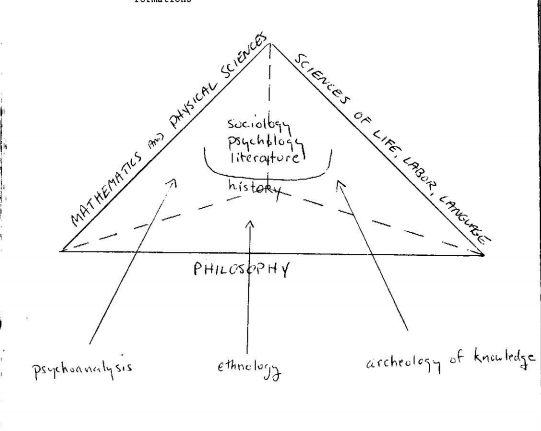

In 1978, Wade published the interview in what may be the most populist of mediums—the fanzine. Titled Chez Foucault, with a dedication “for Michael Stoneman,” the mimeographed document looks on its face like a typical handmade self-publication from the period, with its murky lettering and generally haphazard design. But inside, Chez Foucault is far denser than any chapbook or rock ‘zine. In his preface, Wade describes Chez Foucault as “a workbook I tinkered together for teachers and students in the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences.” Accordingly, in addition to the interview, he includes a synopsis of Foucault’s Discourse on Language, a “transcription” of his Discipline and Punish, a sketch of “The Early Foucault,” and a bibliography, glossary, reading and film list, and veritable course outline. It’s a very rich text that provides a thorough introduction to many of Foucault’s major works. Of principle interest, however, is the interview, seemingly unpublished anywhere else. In it, Foucault elaborates on several of his key concepts, such as the relationship between discourse and power:

I do not want to try to find behind the discourse something which would be the power and which would be the source of the discourse […]. We start from the discourse as it is! […] The kind of analysis I make does not deal with the problem of the speaking subject, but looks at the ways in which the discourse plays a role inside the strategical system in which the power is involved, for which power is working. So power won’t be something outside the discourse. Power won’t be something like a source or the origin of discourse. Power will be something which is working through the discourse.

This concise explanation offers a key to Foucault’s method. Disavowing the labels of both philosopher and historian (he calls himself a “journalist”), Foucault defines his program as “an analysis of discourse, but not with the perspective of ‘point of view.’” (If the distinction is confusing, a reading of his essay “What is an Author?” may help clarify things.) Foucault discusses the biopolitics of power, calling the human body “a productive force,” which “exists in and through a political system.” He also talks about the “political use” of a critical theory such as his, and the possibility of revolutionary philosophy:

I do not think there is such a thing as a conservative philosophy or a revolutionary philosophy. Revolution is a political process; it is an economic process. Revolution is not a philosophical ideology. And that’s important. That’s the reason why something like Hegelian philosophy has been both a revolutionary ideology, a revolutionary method, a revolutionary tool, but also a conservative one. Look at Nietzsche. Nietzsche brought forth wonderful ideas, or tools if you like. He was used by the Nazi Party. Now a lot of Leftist thinkers use him. So we cannot be sure if what we are saying is revolutionary or not.

There is much more worth reading in Foucault’s interview with Wade and his fellow students, and students and teachers of Foucault will find all of Chez Foucault worthwhile. You can read and download the entire Foucault ‘zine here. And lest you think it’s the only one of its kind, don’t miss Judy!, the 1993 fanzine devoted to philosopher Judith Butler.

via Progressive Geographies and Monoskop

Related Content:

Watch a “Lost Interview” With Michel Foucault: Missing for 30 Years But Now Recovered

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply