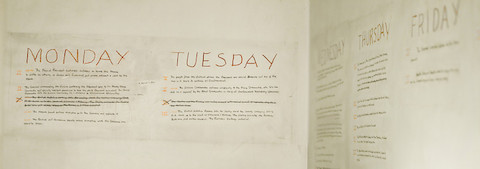

Image courtesy of enotes

This past summer I had occasion to visit Oxford Mississippi for a conference on William Faulkner, hosted by the university he briefly attended, Ole Miss. Owner of Faulkner’s estate, Rowan Oak, since 1972, the university often stages events on the novelist’s former grounds—particularly to celebrate meetings devoted to his work. While I had wandered around the property a few times during my stay on campus, I thought I’d wait until the capstone barbecue at the conference’s close to enter the house itself. More fool me. A rainstorm forced the festivities into a college hall, and I had to depart early the following morning.

And so, sadly, I missed out on walking Faulkner’s floorboards, peering out through his windows, and, especially, seeing firsthand the notes he scrawled on the walls of his study to outline the plot of his 1954 novel A Fable. The Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning book, which—depending on your tolerance for Faulkner’s excesses is either a “crowning achievement or self-indulgent mess”—occupied the author for over a decade. He began A Fable—set in France during World War 1—just after the end of the Second World War, and did much of the writing in the small office he added to the house in 1950, the year after he won the Nobel Prize. (Hear him read his Nobel Prize Speech here.)

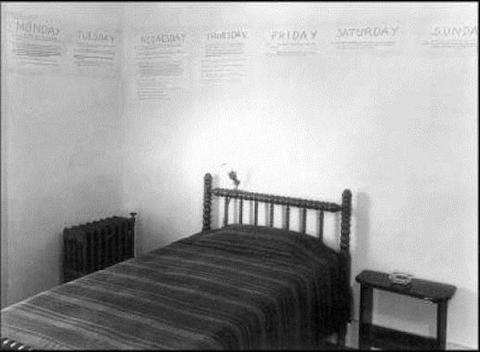

Photo by Nick Russell

Plotting the chronology on the walls helped him become fully immersed in the novel’s density, but, writes education blog Enotes, “not everybody was so pleased with the method”: “Faulkner’s wife, disappointed with the decision, had the walls repainted. In return, Faulkner rewrote the outline and then shellacked the wall to ensure a permanent record.”

There are much worse ways to antagonize one’s spouse, I suppose, but I’m sure that wasn’t his primary intent. Faulkner considered the novel his masterpiece—Pulitzer and National Book Award committees agreed—but critics have not been so kind. It’s now one of his lesser-known works, one of the few not set in the fictional Yoknopatawpha, a stand-in for his own Lafayette county, which he mined for stories all of his mature career after some brief adventuring abroad.

Perhaps his defiant preservation of the plan for A Fable represents his deep desire to leave behind the “postage stamp” of Oxford and its surrounds—to venture into other imaginative territories. If so, his plan failed. Faulkner will be forever associated with the South—with Mississippi, and with Rowan Oak. And like so many devotees, I’ll likely make my pilgrimage to his well-preserved home a yearly event. The next time I’m down there, however, I’ll actually make it inside to see the writing on the walls.

Photo by John Lawrence, from Faulkner’s Rowan Oak , by John Lawrence and Dan Hise

Related Content:

Rare Audio: William Faulkner Names His Best Novel, And the First Faulkner Novel You Should Read

William Faulkner Reads His Nobel Prize Speech

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

How Famous Writers — From J.K. Rowling to William Faulkner — Visually Outlined Their Novels

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thanks for the eNotes link back! Great write up!

-Samantha B.

Marketing Manager @ eNotes

The second I saw that writing on the wall I thought, bipolar, I’ve seem quite a bit of bipolar writing on walls, remarkably similar with different people, love of authoritative commanding capitals seems to be universal. So I googled Faulkner, there do seem to be quite a few claims he was bipolar, including at least one in a book. I don’t know if this is contested.