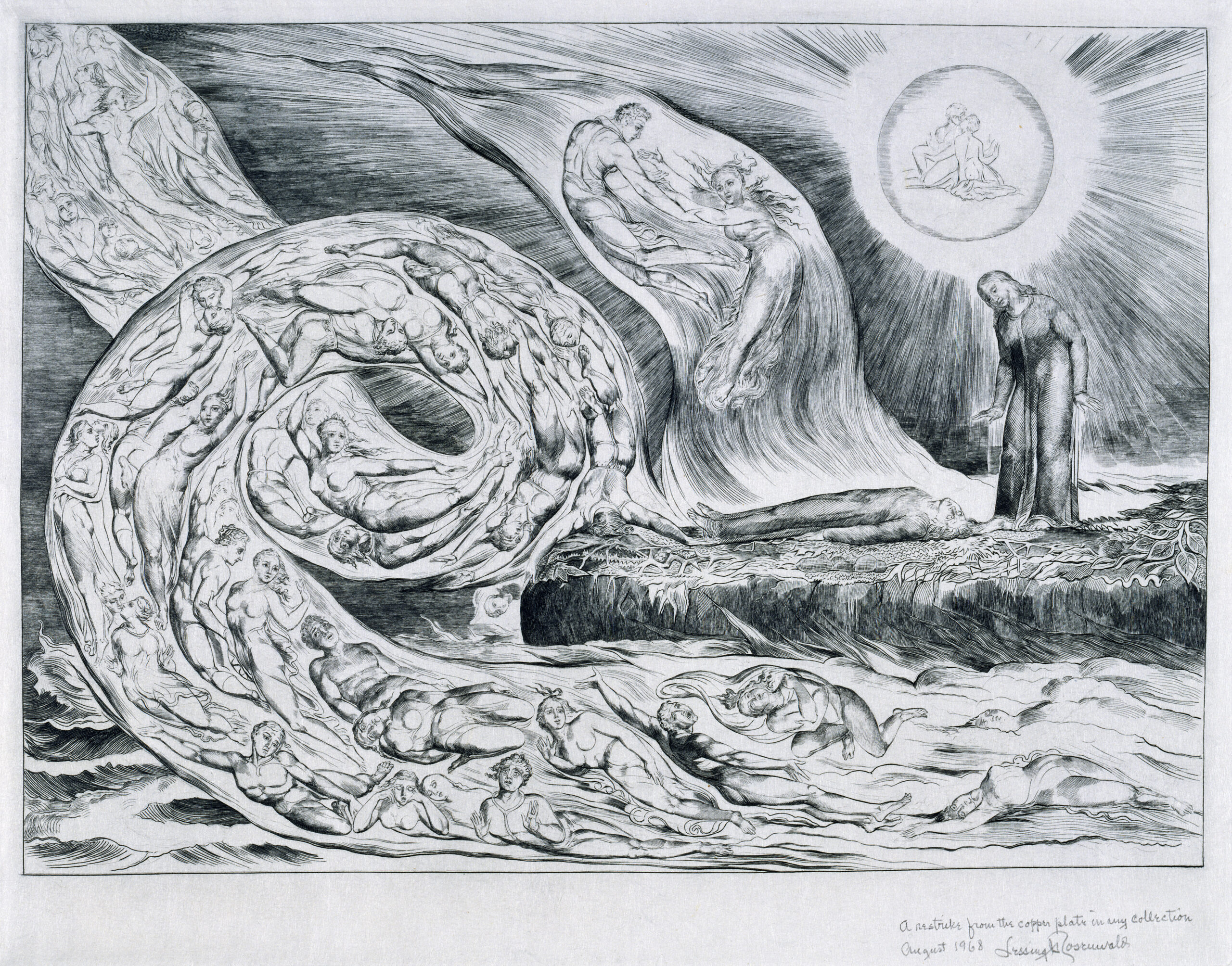

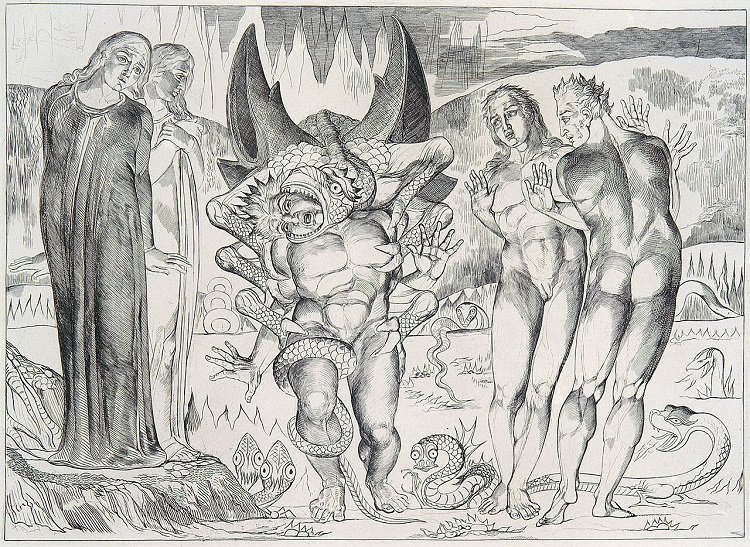

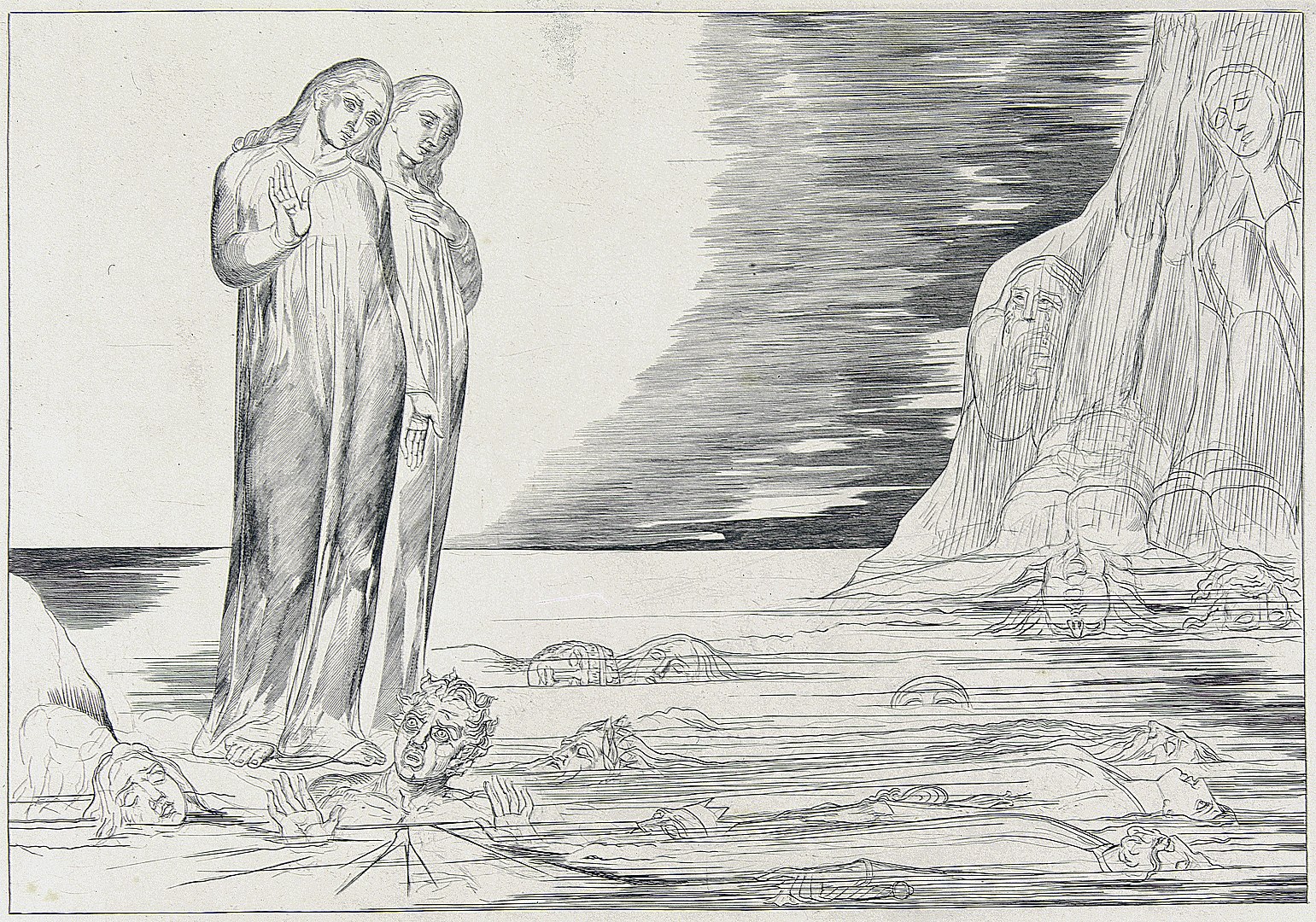

Just over a year ago, we featured John Milton’s Paradise Lost as illustrated by William Blake, the 18th- and 19th-century English poet, painter, and printmaker who made uncommonly full use of his already rare combination of once-a-generation literary and visual aptitude. Blake may have had an obsession with Paradise Lost, as Josh Jones pointed out in that post, but it hardly kept him from illustrating other texts. Today we have his artistic accompaniment to that text that has gone under the hands of Salvador Dalí, Gustave Doré, Alberto Martini, Sandro Botticelli, and Mœbius, to name a few: Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

Blake never completed the full set of engravings commissioned, but only because death itself cut the project short. Still, he managed to complete several watercolors and a handful of engraving proofs, all of which have drawn praise not just for the way they evoke the different environments of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso, but for how they cast a sometimes critical eye on the theological and moral sensibilities of Dante’s original work.

(“Every thing in Dantes Comedia shews That for Tyrannical Purposes he has made This World the Foundation of All & the Goddess Nature & not the Holy Ghost,” Blake once wrote to himself in a piece of marginalia often cited by scholars of this particular project.)

Yet Blake and Dante had common ground. “Blake was drawn to the project because, despite the five centuries that separated them, he resonated with Dante’s contempt for materialism and the way power warps morality — the opportunity to represent these ideas pictorially no doubt sang to him,” writes Maria Popova at Brain Pickings, who tells more of the story surrounding Blake’s Divine Comedy. He stopped only when just about to step off this mortal coil, a moment in which history has remembered him saying to his wife, “Keep just as you are — I will draw your portrait — for you have ever been an angel to me.” That portrait didn’t survive, but what he completed of his Dante illustrations did, granting them the status of William Blake’s final work — and, given the post-life nature of its subject matter, a suitable status indeed.

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Mœbius Illustrates Dante’s Paradiso

Botticelli’s 92 Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Alberto Martini’s Haunting Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1901–1944)

Salvador Dalí’s 100 Illustrations of Dante’s The Divine Comedy

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

From the same series is his depiction of Mohammed, splitting himself apart:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d7/Dante_and_Virgil_Meet_Muhammad_and_His_Son-in-law,_Ali_in_Hell.jpg