Image via Wikimedia Commons

I have not had the occasion to meet my intellectual or literary heroes, those still alive, of course. And from most of the accounts of those who have, it’s probably for the best. I’ve heard stories from mentors and friends—of drunken indiscretions, boorish rudeness, unforgiveable utterances, arrogance, pettiness, petulance, and every other kind of offputting behavior. Our idols, after all, are only human.

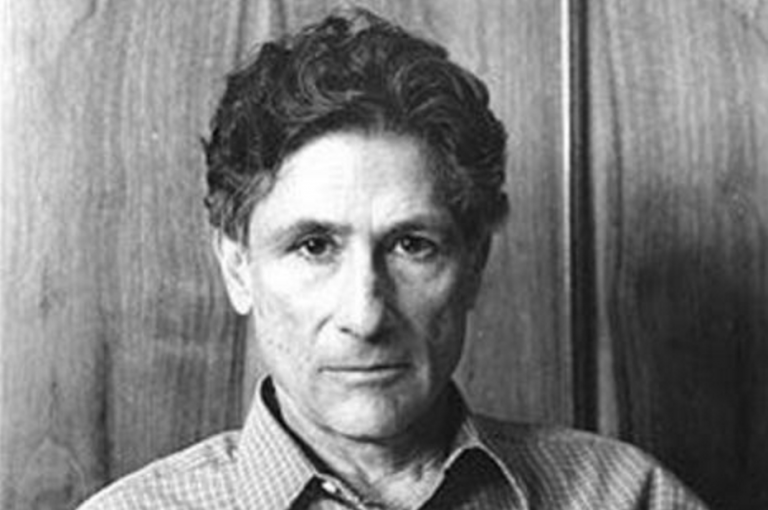

Such disappointment was the experience of Palestinian American scholar and writer Edward Said when he met three intellectual French giants—Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Michel Foucault—in 1979. Invited to France by Sartre and de Beauvoir for a conference on Middle East peace after the end of the war between Egypt and Israel, Said leapt at the chance, although not before ensuring that the telegram he had received was genuine.

“At first I thought the cable was a joke of some sort,” wrote Said in the London Review of Books in 2000, “It might just as well have been an invitation from Cosima and Richard Wagner to come to Bayreuth, or from T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf to spend an afternoon at the offices of the Dial.”

Image via Wikimedia Commons

The invitation was for real, and weeks later, Said was off to Paris. Upon arrival, he learned that for undefined “security reasons,” the conference had been moved to Foucault’s apartment, and once there, he encountered de Beauvoir, who quickly left an unfavorable impression on him, then disappeared.

Beauvoir was already there in her famous turban, lecturing anyone who would listen about her forthcoming trip to Teheran with Kate Millett, where they were planning to demonstrate against the chador; the whole idea struck me as patronising and silly, and although I was eager to hear what Beauvoir had to say, I also realised that she was quite vain and quite beyond arguing with at that moment. Besides, she left an hour or so later (just before Sartre’s arrival) and was never seen again.

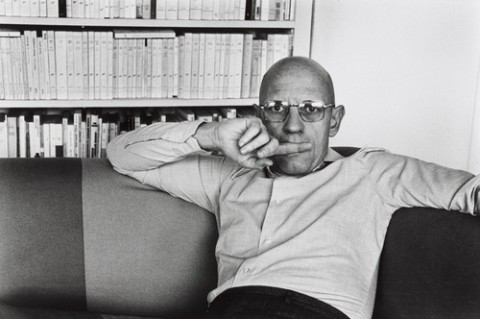

Not long afterwards, Said writes, Foucault informed him he would be leaving as well, “for his daily bout of research at the Bibliothèque Nationale.” Said describes Foucault as a “solitary philosopher” and “rigorous thinker” but also “unwilling to say anything to me about Middle Eastern politics”—with the exception of the Iranian Revolution (for which he was partly present). Foucault described his time in Iran as “very exciting, very strange, crazy.” “I think (perhaps mistakenly) I heard him say that in Teheran he had disguised himself in a wig,” Said writes, “although a short while after his articles appeared, he rapidly distanced himself from all things Iranian.” Foucault also, apparently, distanced himself from the discussion at hand because, Said surmises, of his support for Israel.

Sartre, it appears from Said’s account, was very much at the center of the event. And yet, he seemed “old and frail,” and “was constantly surrounded, supported, prompted by a small retinue of people on whom he was totally dependent.” At lunch, Said finds the “great man” almost as absent mentally as his partner was physically. Where “Beauvoir had been a serious disappointment,” he was later “convinced she would have livened things up.”

Sartre’s presence, what there was of it, was strangely passive, unimpressive, affectless. He said absolutely nothing for hours on end. At lunch he sat across from me, looking disconsolate and remaining totally uncommunicative, egg and mayonnaise streaming haplessly down his face. I tried to make conversation with him, but got nowhere. He may have been deaf, but I’m not sure. In any case, he seemed to me like a haunted version of his earlier self, his proverbial ugliness, his pipe and his nondescript clothing hanging about him like so many props on a deserted stage.

In his sole discourse at the event, Said tells us, Sartre read “a prepared text of about two typed pages” full of “the most banal platitudes imaginable” and “about as informative as a Reuters dispatch.” Afterwards, “Sartre resumed his silence, and the proceedings continued as before.” The politics of the conference were by nature complicated and sensitive, to say the least. Relationships—such as that between Foucault and Gilles Deleuze, it seems (or so Deleuze told Said)—have broken off after disagreements over Israel and Palestine.

Image by Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, on the basis of Sartre’s former anti-colonial, anti-war stance and passionate defense of Algerian independence—a position “which as a Frenchman must have been harder to hold than a position critical of Israel”—Said had hoped Sartre would have at least some sympathy for the Palestinian cause. He was mistaken. “Gone forever, he writes, “was that Sartre.” In a concluding rumination, he attempts to explain what he observed:

I guess we need to understand why great old men are liable to succumb either to the wiles of younger ones, or to the grip of an unmodifiable political belief. It’s a dispiriting thought, but it’s what happened to Sartre. With the exception of Algeria, the justice of the Arab cause simply could not make an impression on him, and whether it was entirely because of Israel or because of a basic lack of sympathy – cultural or perhaps religious – it’s impossible for me to say.

For all its unpleasantness, however, the encounter did not lessen Said’s fondness for Sartre. The author of Orientalism and The Question of Palestine (who is not without his own fierce critics) begins his recollection of the meeting with a glowing appraisal of Sartre’s work, which had fallen far out of favor at the time of the meeting. “A year after our brief and disappointing Paris encounter Sartre died,” he concludes, “I vividly remember how much I mourned his death.”

You can read Said’s complete diary entry here.

Related Content:

Jean-Paul Sartre Breaks Down the Bad Faith of Intellectuals

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Kate Millet exposed as being rather nuts:

http://theothermccain.com/2014/09/01/kate-milletts-tedious-madness/

It’s quiet a shame…an “open” website fails to properly acknowledge and give due credit for an intellectual of Edward Said’s calibre besides this and his last interview. Alas, one of the most erudite writers, one of the founders of post-colonialism along with Gayatri Spivak, has no place in openculture(.com)!

After reading “Adieux to Sartre”–by Beauvoir, with all the details of his last years ilnesses– there´s no reason whatsoever to know such details as referred in this comment

to describe Sartre´s mouth “dripping mayonnaise”

is totally unncecesary and cruel…

It’s surprising that an intellectual of Said’s caliber would lack sensitivity to such an extent. I get the feeling that his idealization/idolization of Sartre didn’t let him see and acknowledge the man for the image he had formed of him. His reaction is reminiscent of a boy shrinking in horror at the sight of his father’s mortality.