It’s hard to overstate the impact of Cahiers du cinéma on film history.

In the early ‘50s, the great critic André Bazin led a small coterie of film fanatics – guys with names like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette — who hung out at the Cinémathèque française. Theaters were flooded with Hollywood movies, really for the first time since the beginning of World War II, and this group took the opportunity to watch anything they could get their hands on, from high brow art films to cut rate Westerns. They would watch anything.

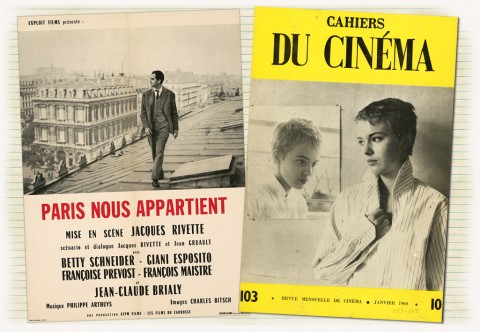

In 1951, Bazin founded Cahiers and this band of cinematic outsiders became famously brutal and uncompromising iconoclasts. They praised lowly genre films – film noir especially – as masterpieces while slamming the middlebrow flicks the French film industry was cranking out at the time. Truffaut was famous for being particularly harsh, earning the moniker “The Gravedigger of French Cinema.” His reviews were so acerbic that he was the only French film critic not invited to cover the 1958 Cannes Film Festival. (The fact that he then turned around and won the fest’s top prize the next year for his masterpiece 400 Blows might be one of the greatest feats of badassery in cinema history.)

Perhaps the Cahiers’ greatest contribution was an article, written by Truffaut in 1954, called “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” which was a manifesto for what would later be called auteur theory – an idea that certain directors have such a command of the medium that they impress their individual vision on a film, in the same way an author does to a book. This idea has been so completely absorbed into popular consciousness that it’s hard to see just how revolutionary it was at the time. Before Cahiers, people generally thought about movies in terms of the stars, not the director. Most would refer to Rear Window, say, as a Jimmy Stewart movie, not an Alfred Hitchcock film. The concept resulted in a basic reordering in the way filmmakers thought about their art.

Truffaut and company obsessed with filmmakers they considered auteurs. Their top 10 list for 1955, the year after “A Certain Tendency” was published, shows who in particular they considered auteurs – art house icons (Carl Dreyer and Roberto Rossellini), Hollywood renegades (Robert Aldrich and Nicholas Ray) and, of course, Hitchcock.

1955

1. Voyage To Italy (Roberto Rossellini)

2. Ordet (Carl Dreyer)

3. The Big Knife (Robert Aldrich)

4. Lola Montes (Max Ophuls)

5. Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock)

6. Les Mauvais Recontres (Alexandre Astruc)

7. La Strada (Federico Fellini)

8. The Barefoot Contessa (Joseph L. Mankiewicz)

9. Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray)

10. Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich)

1960 was the year that seemingly the entire editorial staff at Cahiers du cinéma took camera in hand and became filmmakers, launching the French New Wave. Truffaut’s 400 Blows in 1959 was followed up by Chabrol’s Les Bonnes Femmes and Godard’s groundbreaking assault on cinematic form, Breathless. Yet for their top 10 list, Cahiers put Japanese master Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff at the top. Hitchcock also makes the list, number 9, with a little film called Psycho.

1960

1. Sansho The Bailiff (Kenji Mizoguchi)

2. L’avventura (Michaelangelo Antonioni)

3. Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard)

4. Shoot The Piano Player (François Truffaut)

5. Poem Of The Sea (Alexander Dovzhenko/Julia Solntesva)

6. Les Bonnes Femmes (Claude Chabrol)

7. Nazarin (Luis Buñuel)

8. Moonfleet (Fritz Lang)

9. Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock)

10. Le Trou (Jacques Becker)

Starting from 1968 until the late-70s, the journal became a Maoist collective and renounced bourgeois concepts like “best of” lists, narrative cinema and, y’know, fun. But in the early ‘80s, Cahiers shifted its editorial focus back to the world of commercial film. They lauded movies by Nouvelle Vague veterans like Godard and Rohmer, film festival darlings like Hou Hsiao Hsien and, to a perverse degree, Clint Eastwood. You can see all of Cahiers du cinéma’s top 10 lists here, including the most recent list for 2014 here.

Related content:

Alfred Hitchcock on the Filmmaker’s Essential Tool: ‘The Kuleshov Effect’

Jefferson Airplane Wakes Up New York; Jean-Luc Godard Captures It (1968)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

I’ve always wondered whether Truffaut got his title for “Shoot the Piano Player” from an anecdote Oscar Wilde once told about a western stop he made on a literary tour of America. I’m guessing Wilde was visiting a rather rough-and-tumble saloon with a honky-tonk piano, because next to it was posted a sign reading “Please don’t shoot the piano player. He’s doing the best he can.”

Correction: in “Impressions of America”, Wilde actually portrays the sign he saw in Leadville, Colorado. It reads:

| PLEASE DO NOT SHOOT THE PIANIST. |

| HE IS DOING HIS BEST. |