Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the work he is most known for in death, had the effect in life of ruining his literary reputation and driving him into obscurity. This is but one of many ironies attending the massive novel, first published in Britain in three volumes on October 18, 1851. At that time, it was simply called The Whale, and as Melville.org informs us, was “expurgated to avoid offending delicate political and moral sensibilities.” One month later, the first American edition appeared, now titled Moby Dick; Or, The Whale, compiled into one huge volume, and with its censored passages, including the Epilogue, restored. In both printings, the book sold poorly, and the reviews—save those from a handful of American critics, including Melville’s fellow Great American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne—were largely negative.

Another irony surrounding the novel is one nearly everyone who’s read it, or tried to read it, will know well. We’re socialized through visual media to approach the story as great, tragic action/adventure. As Melville’s friend, publisher Evert Augustus Duyckinck, described it, the novel is ostensibly “a romantic, fanciful & literal & most enjoyable presentment of the Whale Fishery,” driven by the revenge plot of mad old Captain Ahab. And yet, it is not that at all, or not simply that. Despite the fact that it lends itself so well to adventurous retelling, the novel itself can seem very obscure, ponderous, and digressive to a maddening degree. The so-called “whaling chapters,” notably “Cetology,” delve deeply into the lore and technique of whaling, the anatomy and physiology of various whale species, and the history and politics of the venture.

Throughout the novel, ordinary objects and events—especially, of course, the whale itself—acquire such symbolic weight that they become almost cartoonish talismans and leap bewilderingly out of the narrative, forcing the reader to contemplate their significance—no easy task. Depending on your sensibilities and tolerance for Melville’s labyrinthine prose, these very strange features of the novel are either indispensably fascinating or just plain excess baggage. Since many editions are published with the whaling chapters excised, many readers clearly feel they are the latter. That is unfortunate, I think. It’s one of my favorite novels, in all its baroque overstuffedness and philosophical density. But there’s no denying that it works, as they say, “on many levels.” Depending on how you experience the book—it’s either an incredibly gripping adventure tale, or a very dense and puzzling work of history, philosophy, politics, and zoology… or both, and more besides….

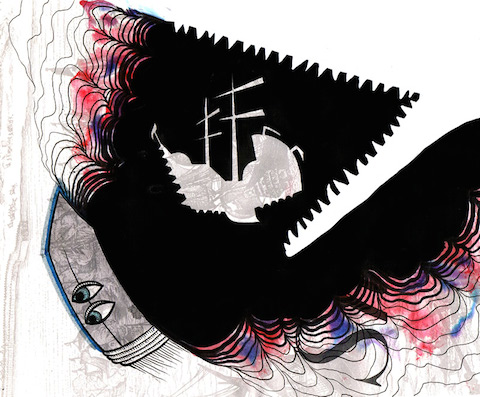

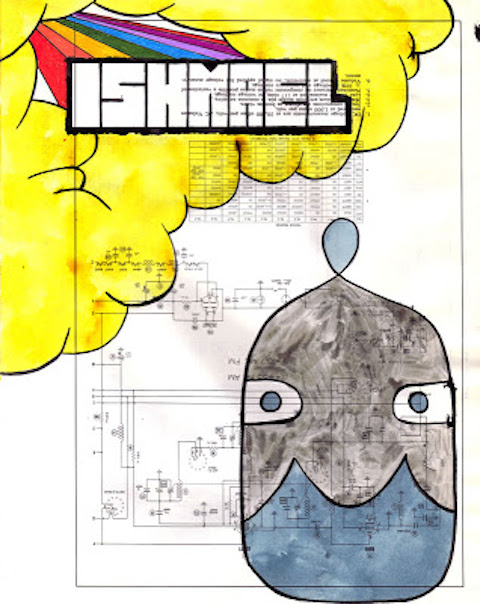

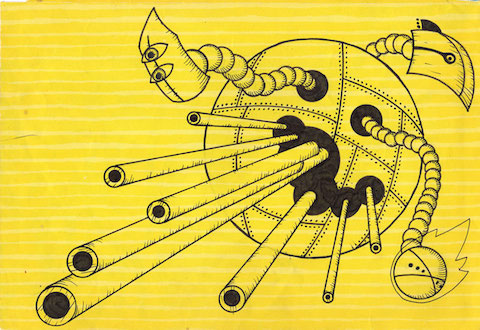

Recognizing the power of Melville’s arresting imagery, artist and librarian Matt Kish decided that he would illustrate all 552 pages of the Signet Classic paperback edition of Moby Dick, a book he considers “to be the greatest novel ever written.” He began the project in August of 2009 with the first page, illustrating those famous first words—“Call me Ishmael”—above. (At the top, see page 489, below it page 158, and directly below, page 116). Kish completed his epic project at the end of 2010. He used a variety of media—ink, watercolor, acrylic paint—and incorporated a number of different graphic art styles. As he explains in the comments under the first illustration, he chose “drawing and painting over pages from old books and diagrams because the presence of visual information on those pages would in some ways interfere with, and clutter up, my own obsessive control over my marks.” All in all, it’s a very admirable undertaking, and you can see each individual illustration, and many of the stages of drafting and composition, at Kish’s blog or on this list we’ve compiled. (You can also find links to the first 25 pages at bottom of this post.) The entire project has also been published as a book, Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page, a further irony given the obsessive literariness of Melville’s novel, a work as obsessed with language as Captain Ahab is with his great white nemesis.

Nonetheless, what Kish’s project further demonstrates is the seemingly inexhaustible treasure house that is Moby Dick, a book that so richly appeals to all the senses as it also ceaselessly engages the intellect. Kish has gone on to apply his wonderful interpretive technique to other classic literary works, including Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. These projects are equally striking, but it’s Moby Dick, “the great unread American novel,” that most inspired Kish, as it has so many other artists and readers.

- MOBY-DICK, Page 025

- MOBY-DICK, Page 024

- MOBY-DICK, Page 023

- MOBY-DICK, Page 022

- MOBY-DICK, Page 021

- MOBY-DICK, Page 020

- MOBY-DICK, Page 019

- MOBY-DICK, Page 018

- MOBY-DICK, Page 017

- MOBY-DICK, Page 016

- MOBY-DICK, Page 015

- MOBY-DICK, Page 014

- MOBY-DICK, Page 013

- MOBY-DICK, Page 012

- MOBY-DICK, Page 011

- MOBY-DICK, Page 010

- MOBY-DICK, Page 009

- MOBY-DICK, Page 008

- MOBY-DICK, Page 007

- MOBY-DICK, Page 006

- MOBY-DICK, Page 005

- MOBY-DICK, Page 004

- MOBY-DICK, Page 003

- MOBY-DICK, Page 002

- MOBY-DICK, Page 001

Related Content:

A View From the Room Where Melville Wrote Moby Dick (Plus a Free Celebrity Reading of the Novel)

How Ray Bradbury Wrote the Script for John Huston’s Moby Dick (1956)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

You guys know about the artist who illustrated every page of Gravity’s Rainbow?

http://www.complex.com/pop-culture/2013/01/25-ridiculous-coffee-table-books/pictures-showing-what-happens-on-each-page

His work on Gravity’s Rainbow was (obviously) a huge inspiration for me and is absolutely breathtaking to behold.