“Jazz is dead.” You can imagine how that statement, potentially inflammatory even today, shook things up when filmmaker Edward Bland dared to say it in 1958. He didn’t cause the stir so much by saying the words himself, but by putting them in the mouth of Alex, one of the main characters in his controversial “semi-documentary” The Cry of Jazz. Alex appears in the film as one of seven members of a racially mixed jazz appreciation society, stragglers who stay behind after a meeting and fall into a conversation about the nature, origin, and future of jazz music. “Thanks a lot, Bruce, for showing me how rock and roll is jazz,” says an appreciative Natalie, one of the white women, to one of the white men. Enter, swiftly, Alex, one of the black men:

“Bruce? Did you tell her that rock and roll was jazz?”

“Yeah, sure. That’s what I told her. Is there something wrong with that?”

“Bruce, how square can you get? Rock and roll is not jazz. Rock and roll is merely an offspring of rhythm and blues.”

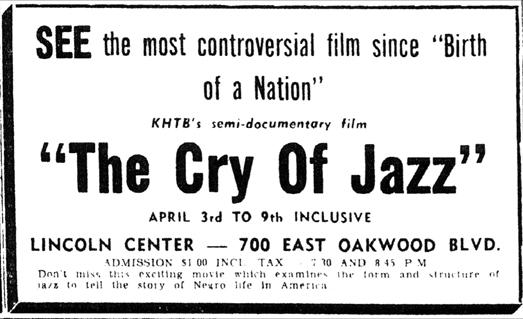

Debate ensues, but Alex ultimately prevails, leaving all races present speechless with his ability to unite the narrative of jazz music with the narrative of the black American experience. We have here less a fiction film or a documentary than a type of heated didactic essay — a cry itself, in some sense — unlike any other motion picture on the subject. “The movie caused an uproar,” writes the New York Times’ Paul Vitello in Bland’s 2013 obituary. “Notable intellectuals took sides. The novelist Ralph Ellison called it offensive. The poet LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka, called it profoundly insightful. An audience discussion after a screening in 1960 in Greenwich Village became so heated that the police were called. The British critic Kenneth Tynan, in a column for The London Observer, wrote that it ‘does not really belong to the history of cinematic art, but it assuredly belongs to history’ as ‘the first film in which the American Negro has issued a direct challenge to the white.’ ”

Where The Cry of Jazz operates most straightforwardly as a documentary, it captures the era’s extant styles of jazz (whether you consider them living or, as Alex insists, dead) as performed by the composer-bandleader Sun Ra and his Arkestra just a few years before his total self-transformation into a sci-fi pharaoh. This provides a “pulsating track of sound under the narration and serves to punctuate the protagonist’s long, engrossing lecture with appropriate segments of performance footage and musical counterpoint,” writes poet John Sinclair. “Inquisitive viewers may gain immensely from exposure to Bland’s fiercely iconoclastic exposition on the state of African American creative music on the historical cusp of the modern jazz era and the free jazz, avant garde, New Black Music movement of the 1960s.” And on the issue of the death of jazz, I submit for your consideration just four of the albums that would come out the next year: Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, Charles Mingus’ Mingus Ah Um, the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Time Out, and Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue. A topic covered in the film, 1959: The Year that Changed Jazz.

Find more great documentaries in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Jazz ‘Hot’: The Rare 1938 Short Film With Jazz Legend Django Reinhardt

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

at least here, it’s not embedded.