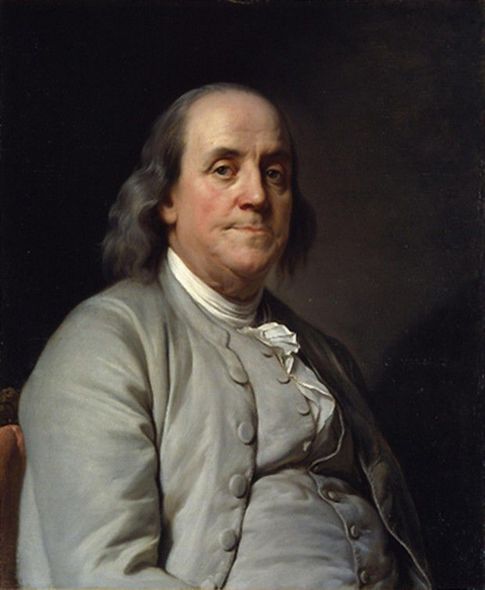

Benjamin Franklin might have been a brilliant author, publisher, scientist, inventor and statesman, but he was pretty lousy at keeping state secrets. That’s the finding from a recently declassified CIA analysis of Franklin’s critically important diplomatic mission to France during the Revolutionary War.

In September 1776, Franklin was dispatched to Paris to enlist France’s support for the American Revolution. At the time, France was still smarting from losing the Seven Years’ War to Britain and was eager to do anything that could reduce its rival’s power and prestige. Franklin’s Commission ran all kinds of clandestine operations with tacit French aid, including procuring weapons, supplies and money for the American Army; sabotaging the Portsmouth Royal Navy Dockyard; and negotiating a secret treaty between America and France.

And according the CIA’s in-house publication, Studies in Intelligence, the British knew just about everything that was going on. “The British had a complete picture of American-French activities supporting the war in America and of American intentions regarding an alliance with France. The British used this intelligence effectively against the American cause.”

Some of the problems with the Commission seem head-slappingly obvious. “There was no real physical security at the Commission itself. The public had access to the mansion, documents and papers were spread out all over the office, and private discussions were held in public areas.”

One of Franklin’s fellow commissioners, Arthur Lee, was outraged over this lack of security.

[Lee] wrote that a French official “had complained that everything we did was known to the English ambassador, who was always plaguing him with the details. No one will be surprised at this who knows that we have no time or place appropriate to our consultation, but that servants, strangers, and everyone else was at liberty to enter and did constantly enter the room while we were talking about public business and that the papers relating to it lay open in rooms of common and continual resort.

Not surprisingly, the American mission was riddled with British spies; chief among them was Franklin’s long-time friend Edward Bancroft, who, as the Commission’s secretary, had complete access to all of its papers. He was reportedly paid a princely sum of 1000 pounds a year by the British Empire to play the part of an Enlightenment-era James Bond.

Lee suspected Bancroft of being a spy, but Franklin dismissed his concerns largely because he greatly disliked Lee. “[Franklin’s] attitude … is all too familiar among policymakers and statesmen,” writes the CIA. “His ego may have overwhelmed his common sense.”

In the end, the analyst lays the blame on these catastrophic lapses in intelligence on that inflated ego.

“By the time [Franklin] arrived in Paris in late 1776, he was elderly and had little interest in the administrative aspects of the Commission. Franklin was widely recognized as a statesman, scientist, and intellectual. While highly respected, he was also vain, obstinate, and jealous of his prerogatives and reputation. … The Commission was “under protection” of the French Government, and Franklin may have underestimated British capabilities to operate in a third country. In any event, he did nothing to create a security consciousness at the Commission.”

The portrait that the CIA paints is indeed a grim one that in different circumstances could have lost the war. Thankfully, Britain proved wholly unable to use this wealth of information to turn the tide of the war. As the CIA wryly notes: “Perhaps the greatest irony in the whole story of the penetration of the American Commission is that, while British intelligence activities were highly successful, British policy was a total failure.”

Related Content:

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

So the CIA has an in house magazine that is classified? I’m having a difficult time understanding why.