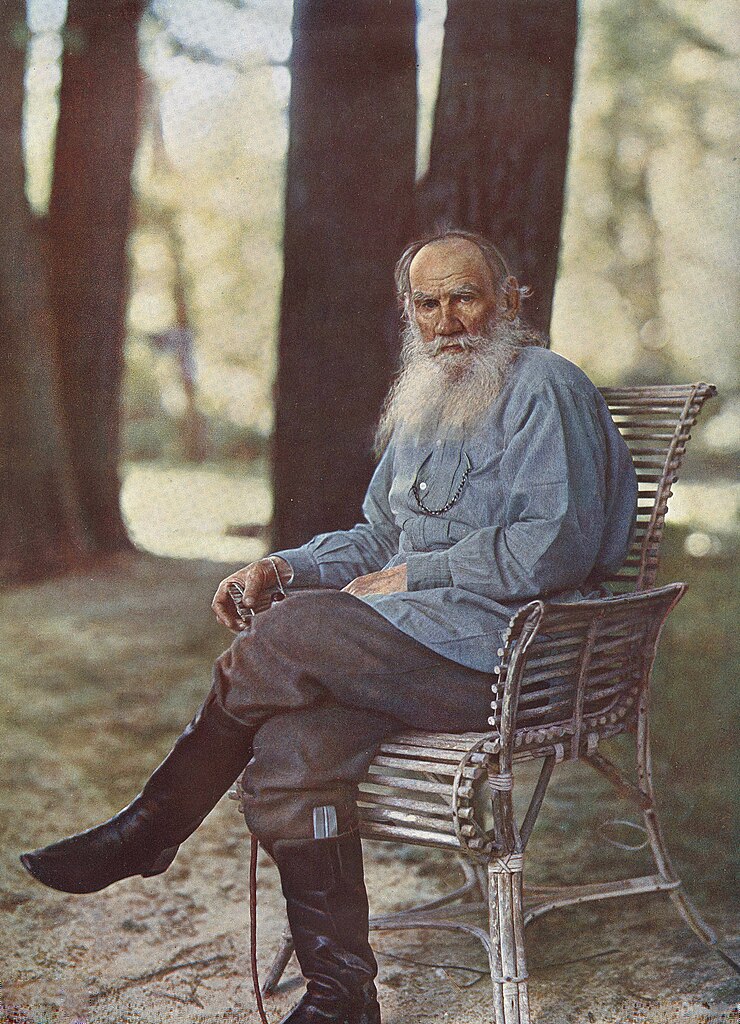

A good few people objected to a recent project that colorized old photos of Walt Whitman, Charlie Chaplin, Helen Keller, Mark Twain, and other historical characters. Leave them alone! they grumped. The past, they wanted left in black and white. But this is not so easily done when some photos—whether of august personages like Leo Tolstoy above, or of ordinary anonymous peasants below—were always processed in color. The Tolstoy image dates from 1908, two years before his death, but the process is much older, and successful color photographs, not simply hand-painted colorizations, go back at least to the Lumiere Brothers’ Autochromes from the late 19th century.

The method that gave us Tolstoy in color involved taking three photographs—with a red, a green, and a blue filter—then projecting the resulting prints through filters of the same color. It’s a procedure that dates to Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell’s 1861 experiments, which put to the test several earlier theories. The photographs you see here are the work of scientist and inventor Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky, who had perfected the projection method to such a degree that—as he wrote in a letter to Tolstoy asking him to pose—he only needed “from 1 to 3 seconds to take the photograph.” Thus it would not be “overly tiresome” for the soon-to-be eighty-year-old novelist.

Tolstoy, of course, was a national institution, and had warranted an earlier attempt at a color portrait by an anonymous amateur to whom Prokudin-Gorsky refers in his letter of request. The first attempt, the inventor implies, was a botched job. Billing himself as a specialist in “photography ‘in natural colors,’” the self-confident entrepreneur assured the writer he could produce “excellent results” with “accurate colors.” “My colored projections,” he wrote, “are known in both Europe and in Russia.” Prokudin-Gorsky was received and given two days to take several color photographs, though whether the others have survived, I do not know. We do know that the portrait appeared in the August, 1908 issue of The Proceedings of the Russian Technical Society as “the first Russian color photoportrait.” The journal offered the image in tribute to Tolstoy’s upcoming 80th birthday celebration, writing:

Our periodical, as a purely technical one, cannot honor this venerable representative of Russian thought and word with special articles. Desiring, however, to take part in the general festivities, the editorial staff […] decided to publish in this, its August issue, the newest portrait of Tolstoy, which is the dernier mot in photographic technology. The portrait was taken on location and in natural colors, achieved through technical methods alone, without any use of the artist’s brush or tool.

Prokudin-Gorsky expressed his gratitude to the novelist by mailing him a photographic periodical containing “many pictures produced in my workshops from my photographs.” Perhaps the other photos we see here were contained in that journal. Prokudin-Gorsky had every reason to be proud of his work, and the Russian Technical Society every reason to endorse it. The pictures are stunning.

Some of the photographs, like the Tolstoy portrait, have a painterly, almost impressionistic quality. Others, like the 1911 village scene with the Nikolaevskii Cathedral in the distance, have almost the depth of field and fine-grained clarity of 35mm film. And some, like that of the already cartoonish structure below, have an almost hallucinatory CGI quality. The method wasn’t perfect—even with such short exposures, subjects had to remain absolutely still. If they moved, the result was an eerie double exposure effect you see in the middle distance of the field workers photographed above. But overall, these photographs simply astonish in their crispness and fidelity.

You can see many more of Prokudin-Gorsky’s images at this online gallery, which includes over a dozen early-twentieth century photos of Russian laborers, landscapes, and self portraits. Prokudin-Gorsky’s work also preserves images of various Eastern European peoples in traditional dress—like the final Emir of Bukhara, now Uzbekistan, below in 1910. Many of these groups were on the verge of cultural extinction in the coming years of Soviet imperialism. Unwittingly, Prokudin-Gorsky managed to beautifully capture the very end of tsarist Russia, most poignantly symbolized for so many Russians by their aged literary hero, whose birthday we celebrate again today. Google decided to do so in full color as well, with fancy doodles of his major works. You may accuse them of tampering with the past, but those who find these color photographs too modern may need to expand their definition of modernity.

Related Content:

Colorized Photos Bring Walt Whitman, Charlie Chaplin, Helen Keller & Mark Twain Back to Life

Rare Recording: Leo Tolstoy Reads From His Last Major Work in Four Languages, 1909

Vintage Footage of Leo Tolstoy: Video Captures the Great Novelist During His Final Days

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Don’t the colors look too bright?nOld colors were always dusty.

funny thing is that anglo-european racists love to talk about peoples old culture but they never peep into their modern or old racist culture themselves? There got to be some sickness of the brain defining this?

funny thing is that anglo-european racists love to talk about peoples old culture but they never peep into their modern or old racist culture themselves? There got to be some sickness of the brain defining this?

A great work done on the colour aspect giving a vivid window on Russia.

Old film emulsions and paints reproduced colors as dusty. Whether they were dusty to the naked eye is a different question.

Consider fuchsia/magenta. As a dye, it does back to 1859, well before anyone could really reproduce it in images.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuchsia_(color)

I think this is a prejudice born of the fading of much colour film as opposed to 3‑ngative processes. Why should the past have been any more dull than the pesent? Some natural dye colours were dull, but not all. Anyway, skin tones are a reference.