On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. Most of us know this — or at least if we don’t know the exact date, we know it happened in 1914, 100 years ago. We also know that the spark of the killing ignited the international geopolitical tinderbox just waiting to flame into the First World War. Yet as military historians often remind us, no one event can really start a conflict of that unprecedented scale any more than one event can stop it. The second half of the year 1914 saw a series of interrelated crises, responses, counter-crises, and counter responses that, these hundred years on, few of us could cite off the top of our heads.

We can compensate for the century between us and the Great War by reading up on it, of course. Of the countless volumes available, I personally recommend Geoff Dyer’s The Missing of the Somme. But nothing brings home the detailed reality of this ever-more-distant “huge murderous public folly,” in the words of J.B. Priestly, like looking at color photos from the front.

That color photography exists of anything in mid-1910s Europe, much less as momentous and disastrous a period as World War I, still surprises some people. We owe these shots to the efforts of German photographer Hans Hildebrand, as well as to his country’s already-established appreciation for the art and adeptness in engineering its tools. “In 1914, Germany was the world technical leader in photography and had the best grasp of its propaganda value,” writes R.G. Grant in World War I: The Definitive Visual History. “Some 50 photographers were embedded with its forces, compared with 35 for the French. The British military authorities lagged behind. It was not until 1916 that a British photographer was allowed on the Western Front.” But among his countrymen, only Hildebrand took pictures in color.

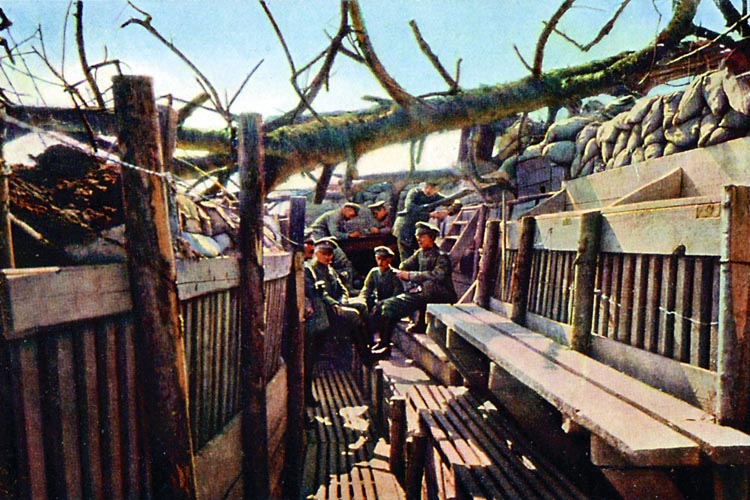

“The overwhelming majority of photos taken during World War I were black and white,” writes Spiegel Online, where you can browse a gallery of eighteen of his photos, “lending the conflict a stark aesthetic which dominates our visual memory of the war.” Hildebrand’s images thus stand out with their almost unreal-looking vividness, a result achieved not simply by his use of color film, but by his relatively long experience with a still fairly new medium. He’d already founded a color film society in his native Stuttgart three years before the Archduke’s assassination, and had tried his hand at autochrome printing as early as 1909.

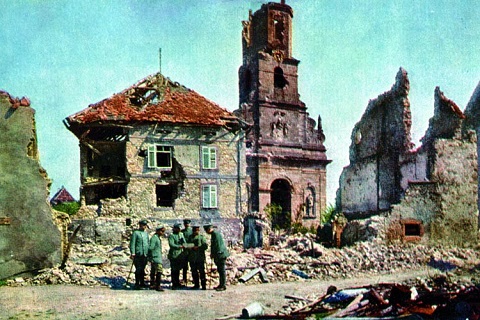

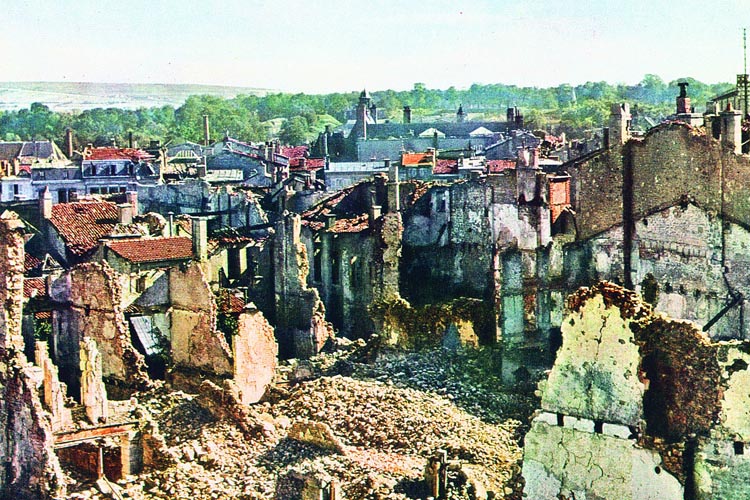

Though not himself a dyed-in-the-wool propagandist, he did need to pose the soldiers for these photos, due to the lack of a film sensitive enough to capture actual action. Still, they give us a clearer idea of the situation than do most contemporary images. Hardly a glorification, Hildebrand’s work seems to speak to what those of us now, one hundred years in the future, would come to see in World War I: its misery, its oppressive sense of futility, and the haunting destruction it left behind.

Related Content:

Watch World War I Unfold in a 6 Minute Time-Lapse Film: Every Day From 1914 to 1918

British Actors Read Poignant Poetry from World War I

Frank W. Buckles, The Last U.S. Veteran of World War I

World War I Remembered in Second Life

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

In ww1 Germany and france declared war om each other despite both their armies being where they’re supposed to be. Both Germany and france had the security system that has every power.

Britain didn’t declare war on Germany until the german army had gone through Belgium. The german army is not supposed to be in Belgium. Britain had mi5 that does agent handling and surveillance, and then police that display badges and arrest people.