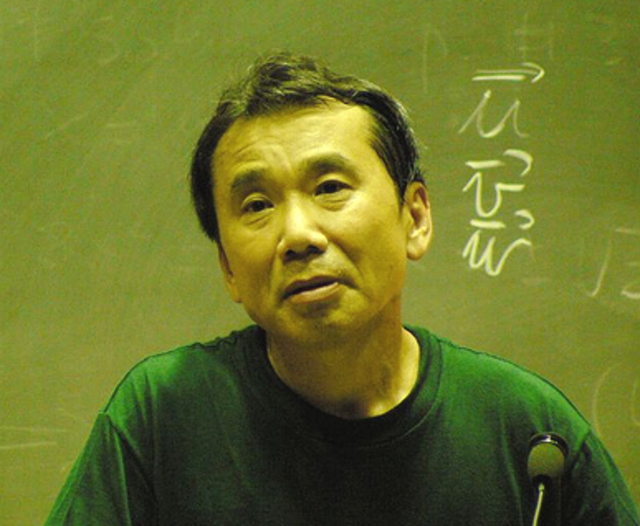

Image by wakarimasita, via Wikimedia Commons

Image by wakarimasita, via Wikimedia Commons

In her New York Times review of Haruki Murakami’s latest, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, Patti Smith writes that the novelist has two modes, “the surreal, intra-dimensional side” and the “more minimalist, realist side.” These two Murakamis often coexist within the same work of fiction, as the fantastic or the supernatural invades the real, or the other way around. Like one of his literary heroes, Franz Kafka, Murakami’s work doesn’t so much create alternate realities as it alters reality, with all its mundane details and humdrum daily routines. As Ted Gioia put it in a review of Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, “this ability to capture the phantasmagorical in the thick of commuter traffic, broadband Internet connections and high-rise architecture is the distinctive calling card of Murakami”—he “mesmerizes us by working his legerdemain in places where reality would seem to be rock solid.”

In Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki Murakami works this same magic, as you can see in this excerpt published in Slate last month. Textured with granular realist details and straightforward narration, the scene slowly builds into a captivating supernatural tale that slides just as easily back into the weft and warp of waking life. In one piece of dialogue, Murakami sums up one way we might read all of his “surreal, intra-dimensional” flights: “It wasn’t an issue of whether or not he believed it. I think he totally accepted it as the weird tale it was. Like the way a snake will swallow its prey and not chew it, but instead let it slowly digest.” Given the jittery, distracted state of most modern readers in a technological landscape that pushes us to make hasty judgments and snappy, ill-considered replies, it is surprising how many of Murakami’s fans are willing to take the time. And it is no subset of cloistered devotees either, but, in Patti Smith’s words, “the alienated, the athletic, the disenchanted and the buoyant.”

Murakami finds readers across this broad spectrum for many reasons; his prose is accessible even when his narratives are baffling. (Gioia notes that “when the Japanese publisher of Kafka on the Shore set up a website allowing readers to ask questions of the author, some 8,000 were submitted.”) His perennial preoccupation with, and immersion in, the worlds of jazz, rock, and classical music, baseball, and running, draw in those who might normally avoid the Kafka-esque. But when we come to Murakami, Kafka-esque is very often what we find, as well as Salinger-esque, Vonnegut-esque, Pynchon-esque, even Philip K. Dick-esque, as well as the –esque of realist masters like Raymond Carver. Whether you’re new to Murakami or a longtime fan of his work, you’ll find all of these tendencies, and much more to love, in the four short stories we present below, all free to read at The New Yorker for a limited time (the magazine will go behind a paywall in the fall).

Take advantage of this brief reprieve and enjoy the many riches of Haruki Murakami’s fictive worlds, which so deceptively impersonate the one most of us live in that we feel right at home in his work until it jolts us out of the familiar and into a “weird tale.” Whether you believe them or not, they’re sure to stay with you awhile.

“Kino” (February 23, 2015)

“A Walk to Kobe” (August 6, 2013)

“Samsa in Love” (October 28, 2013)

“Yesterday” (June 9, 2014)

“Scheherazade” (October 13, 2014)

“Town of Cats,” translated from the Japanese by Jay Rubin (September 5, 2011)

“U.F.O. in Kushiro” (March 28, 2011; originally published March 19, 2001)

“Cream” (January 28, 2019)

“With the Beatles” (February 10, 2020)

“Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey” (June 1, 2020)

“The Kingdom That Failed” (August 13, 2020)

And last but surely not least, we bring you “The Folklore of Our Times” from The Guardian (published August 1, 2003), one of Murakami’s involved realist coming-of-age narratives notable for the mature, almost world-weary insights he draws from the seemingly unexceptional fabric of ordinary experience.

Related Content:

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

who is this guy

In case you’re not trolling, he is a Japanese writer in the tradition of beat-literature and jazzy American pop fiction. But with a surreal and magical-realist twist. He is famous for stories that surprise in how they don’t really make sense, as he bends the natural laws to describe universes where reality melts with the mental states of his characters. Sometimes they seem allegorical, sometimes it seems to be weird just for the fun of wild creativity. He might be the most playful novelist alive today. He has been expected to win the Nobel Prize for years, but maybe his shtick is too samey for the committee, as he tends to repeat the same motifs and tendencies in most of his works.

I love Murakamir“state of mind which is spiritual and magical both at a time.

Thanks for the free offer.

Haruki Murakami is nonpareil. Highly spiritualistic with worldly grandeur. Uncanny mix of extremes — the essence of life itself.