Most everyone who comments on the phenomenon of the supergroup will feel the need to point out that such bands rarely transcend the sum of their parts, and this is mostly true. But it does seem that for a certain period of time in the late sixties, many of the best bands were supergroups, or had at least two or more “super” members. Take the Yardbirds, for example, which contained, though not all at once, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and Eric Clapton. Or Cream, with Clapton, Jack Bruce, and Ginger Baker. Or Blind Faith—with Clapton, Baker, and Steve Winwood…. Maybe it’s fair to say that every band Clapton played in was “super,” including, for a brief time, John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Plastic Ono Band.

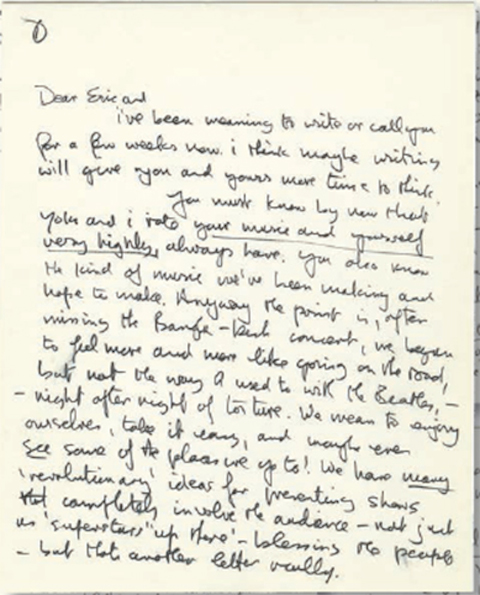

It started with the one-off performance above in Toronto, which led to an undated eight-page letter Lennon wrote Clapton, either in 1969, according to Booktryst, or 1971, according to Michael Schumacher’s Clapton bio Crossroads. The letter we have–well over a thousand words–is a draft. Lennon’s revised copy has not surfaced, and, writes Booktryst, “the content of the final version is unknown.” In this copy (first page at top), Lennon praises Clapton’s work and details his and Yoko’s plans for a “revolutionary” project quite unlike Lennon’s former band. As he puts it, “we began to feel more and more like going on the road, but not the way I used to with the Beatles—night after night of torture. We mean to enjoy ourselves, take it easy, and maybe even see some of the places we go to!”

Lennon explicitly states that he does not want the band to be a supergroup, even as he recruits super members like Clapton and Phil Spector: “We have many ‘revolutionary’ ideas for presenting shows that completely involve the audience—not just as ‘Superstars’ up there—blessing the people.” While Lennon and Ono don’t expect their recruits to “ratify everything we believe politically,” they do state their intention for “’revolutionizing’ the world thru music.” “We’d love to ‘do’ Russia, China, Hungary, Poland, etc.,” writes Lennon. Later in the missive, he explains his detailed plan for the Plastic Ono Band tour he had in mind—involving a cruise ship, film crew, and the band’s “families, children whatever”:

How about a kind of ‘Easy Rider’ at sea. I mean we get EMI or some film co., to finance a big ship with 30 people aboard (including crew)—we take 8 track recording equipment with us (mine probably) movie equipment—and we rehearse on the way over—record if we want, play anywhere we fancy—say we film from L.A. to Tahiti […] The whole trip could take 3–4‑5–6 months, depending how we all felt.

It sounds like an outlandish proposal, but if you’re John Lennon, I imagine nothing of this sort seems beyond reach—though how he expected to get to Eastern Europe from the Pacific Rim on his ship isn’t quite clear. The problem for Clapton, biographer Michael Schumacher speculates, would have had nothing to do with the music and everything to do with his addiction: “after all his problems with securing drugs in the biggest city in the United States, Clapton couldn’t begin to entertain the notion of spending lengthy periods at sea and trying to obtain heroin in foreign countries.” In any case, “in the end, Lennon’s proposal, like so many of his improbable but compelling ideas, fell through.” This may have had some relation to the fact that Lennon had a heroin problem of his own at the time.

The clip of Clapton performing with the band comes from Sweet Toronto, a 1971 film made by D.A. Pennebaker of the band’s performance at the 1969 Toronto Rock and Roll Revival Festival (see the full film above). That event had a wholly improbable lineup of ‘50s stars like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Bo Diddley alongside bands like Alice Cooper, Chicago, and The Doors. As the title opening of the film states, “John could at last introduce Yoko to the heroes of his childhood.” Pennebaker gives us snippets of the performance from each of Lennon’s heroes—opening with Diddley, then Lewis, Berry, and Little Richard—before the Plastic Ono Band with Clapton appear at 16:43. (This performance also produced their first album.) The Beatles Bible has a full rundown of the festival and the band’s somewhat shambolic, bluesy—and with Yoko, screechy—show.

Read the full transcript and see more scans of Lennon’s draft letter to Clapton over at Booktryst, who also explain the cryptic references to “Eric and,” “you both,” and “you and yours”—part of the “soap opera” affair involving Clapton, George Harrison’s (and later Clapton’s) wife Pattie Boyd, and her 17-year-old sister Paula.

Related Content:

In 1969 Telegram, Jimi Hendrix Invites Paul McCartney to Join a Super Group with Miles Davis

John Lennon Plays Basketball with Miles Davis and Hangs Out with Allen Ginsberg & Friends

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

What the hell was Yoko doing??? WTF????

Still too far ahead of our time

Very interested article about John Lennon&Miles Davie playing basketball, here you got two different muscians from two musical spectrum.

No doubt whatsoever that the letter is 1971: it refers to missing the Concert for Bangladesh (Aug 1 1971), and mentions that they’re staying at the St. Regis Hotel likely until the end of October. The arrived there and September, and they moved into their Greenwich Village apartment on October 16, so there’s actually a fairly narrow window in which the letter could have been written in late summer 1971. This is a great article though! I’d never seen that Sweet Toronto clip before!

Giving a hot Michigan to Yoko Ono is never a good idea. I wish Clapton would provide honest commentary on his thoughts about sharing the stage with that screaming banshee. Then again, he may not remember much of those days. Yoko should apologize to humanity for this.

Hot microphone. Not Michigan. Damn spell check.