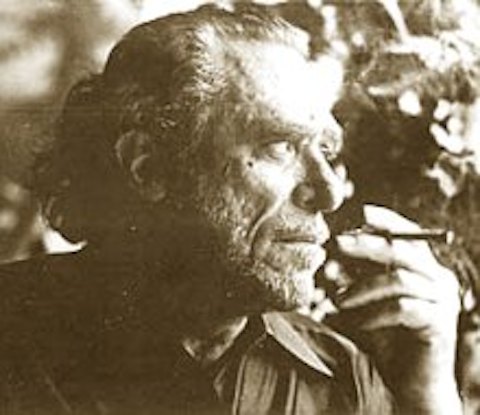

Charles Bukowski—or “Hank” to his friends—assiduously cultivated a literary persona as a perennial drunken deadbeat. He mostly lived it too, but for a few odd jobs and a period of time, just over a decade, that he spent working for the United States Post Office, beginning in the early fifties as a fill-in letter carrier, then later for over a decade as a filing clerk. He found the work mind-numbing, soul-crushing, and any number of other adjectives one uses to describe repetitive and deeply unfulfilling labor. Actually, one needn’t supply a description—Bukowski has splendidly done so for us, both in his fiction and in the epistle below unearthed by Letters of Note.

In Bukowski’s first novel Post Office (1971), the writer of lowlife comedy and pathos builds in plenty of wish-fulfillment for his literary alter ego Henry Chinaski. Kyle Ryan at The Onion’s A.V. Club sums it up succinctly: “In Bukowski’s world, Chinaski is practically irresistible to women, despite his alcoholism, misogyny, and general crankiness.” In reality, to say that Bukowski found little solace in his work would be a gross understatement. But unlike most of his equally miserable co-workers, Bukowski got to retire early, at age 49, when, in 1969, Black Sparrow Press publisher John Martin offered him $100 a month for life on the condition that he quit his job and write full time.

Needless to say, he was thrilled, so much so that he penned the letter below fifteen years later, expressing his gratitude to Martin and describing, with characteristic brutal honesty, the life of the average wage slave. And though comparisons to slavery usually come as close to the level of absurd exaggeration as comparisons to Nazism, Bukowski’s portrait of the 9 to 5 life makes a very convincing case for what we might call the thesis of his letter: “Slavery was never abolished, it was only extended to include all the colors.”

After reading his letter below, you may feel a great deal more sympathy, if you did not already, with Bukowski’s life choices. You may find yourself, in fact, re-evaluating your own.

8–12-86

Hello John:

Thanks for the good letter. I don’t think it hurts, sometimes, to remember where you came from. You know the places where I came from. Even the people who try to write about that or make films about it, they don’t get it right. They call it “9 to 5.” It’s never 9 to 5, there’s no free lunch break at those places, in fact, at many of them in order to keep your job you don’t take lunch. Then there’s OVERTIME and the books never seem to get the overtime right and if you complain about that, there’s another sucker to take your place.

You know my old saying, “Slavery was never abolished, it was only extended to include all the colors.”

And what hurts is the steadily diminishing humanity of those fighting to hold jobs they don’t want but fear the alternative worse. People simply empty out. They are bodies with fearful and obedient minds. The color leaves the eye. The voice becomes ugly. And the body. The hair. The fingernails. The shoes. Everything does.

As a young man I could not believe that people could give their lives over to those conditions. As an old man, I still can’t believe it. What do they do it for? Sex? TV? An automobile on monthly payments? Or children? Children who are just going to do the same things that they did?

Early on, when I was quite young and going from job to job I was foolish enough to sometimes speak to my fellow workers: “Hey, the boss can come in here at any moment and lay all of us off, just like that, don’t you realize that?”

They would just look at me. I was posing something that they didn’t want to enter their minds.

Now in industry, there are vast layoffs (steel mills dead, technical changes in other factors of the work place). They are layed off by the hundreds of thousands and their faces are stunned:

“I put in 35 years…”

“It ain’t right…”

“I don’t know what to do…”

They never pay the slaves enough so they can get free, just enough so they can stay alive and come back to work. I could see all this. Why couldn’t they? I figured the park bench was just as good or being a barfly was just as good. Why not get there first before they put me there? Why wait?

I just wrote in disgust against it all, it was a relief to get the shit out of my system. And now that I’m here, a so-called professional writer, after giving the first 50 years away, I’ve found out that there are other disgusts beyond the system.

I remember once, working as a packer in this lighting fixture company, one of the packers suddenly said: “I’ll never be free!”

One of the bosses was walking by (his name was Morrie) and he let out this delicious cackle of a laugh, enjoying the fact that this fellow was trapped for life.

So, the luck I finally had in getting out of those places, no matter how long it took, has given me a kind of joy, the jolly joy of the miracle. I now write from an old mind and an old body, long beyond the time when most men would ever think of continuing such a thing, but since I started so late I owe it to myself to continue, and when the words begin to falter and I must be helped up stairways and I can no longer tell a bluebird from a paperclip, I still feel that something in me is going to remember (no matter how far I’m gone) how I’ve come through the murder and the mess and the moil, to at least a generous way to die.

To not to have entirely wasted one’s life seems to be a worthy accomplishment, if only for myself.

yr boy,

Hank

via Flavorwire

Related Content:

Charles Bukowski: Depression and Three Days in Bed Can Restore Your Creative Juices (NSFW)

“Don’t Try”: Charles Bukowski’s Concise Philosophy of Art and Life

The Last (Faxed) Poem of Charles Bukowski

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Bukowski = Always to the point and always inspirational.

this is a wonderful way to put things in perspective…

What a pussy.

The guy was a (very) good writer, and he got lucky.

I come from a very blue collar family. We were taught from a very young age that you have to have a steady job, and any job will do better than no job at all. I was lucky and I got out of this habit early in life. There are some honest truths written by Bukowski

Bukowski-THE MAN WHO HAD A VISION TO LOOK BEYOND THOSE FOUR WALLS

Is he wrong though? If you don’t like doing what you do, and you don’t own what you do, you’re a slave. All of us get our souls crushed in one way or another by the 9–5. He was just man enough to admit it, and even manner enough to try and break out (and just lucky enough to succeed). Yes, what a pussy indeed.

Like Hov said, “9–5 is how I survive. I aint tryna survive.”

Though the working conditions Bukowski was employed under and many people are enduring today are horrible I still see some very important differences to slavery:

For example the absence of bodily abuse, the fact that children and elderly were/are not forced to work in the kind of jobs he was working in, the fact that slave’s children could be sold and taken away from their parents, and that Bukowski for sure did not endure the dicriminination due to skin color that justified slavery. I find some definitions of slavery here historically incorrect and offensive.

I agree. ‘Serfdom’ is a word that better describes the condition Bukowski rails against although there are differences there too.

Some people like walls maybe. Not me. One must first live, then die, then die again, then live, then die. It is a slave system. Maybe the whip is gone but it takes the same kind of fortitude to escape

Sea Dawg, you make me want to open myself with expansive thinking. I want to widen my freedom and scream into the wind.

I feel like a lot of these response completely ignore what life was like in America between the 50s and 70s. And, even to a degree, before the internet.

People couldn’t just randomly start weird hipster companies with mommy and daddy’s money like they do now.

And you couldn’t build a ‘brand’ by hopping on Instragram or Snapchat like people do today.

To have your own home or own place, maybe the luxury of a car, healthcare…you had to have a job to get those things and most jobs were pretty miserable because they typically revolved around legitimately hard labor.

If you were in a union, you were considered lucky because you made fair wages and benefits, a vacation and healthcare.

But to jump away from all that was insanity at the time because there were no other options if you were a person of means with rich parents.

Keep that in mind when you’re playing critique. Jumping off that was a ballsy move with seriously dire implications if you didn’t get it right. Hank couldn’t just show up and live in mommy and daddy’s basement like so many adults do these days after their organic, GMO free decaf coffee brand you start doesn’t take off.

Context.

Perspective.

You need both to understand Bukowski’s work and a realization of societal norms during his time to really appreciate what he wrote. It’s great that his message spans across generations and time but if you really want to feel this shit, put it into perspective by way of American norms while this guy was breaking free of what he saw as a modern day slavery.

He wasn’t lucky.

He was smart.

If life for a common man was so bad at that time how worse is it now and how worst it will become tomorrow

exactly. hope that if anyone on this thread sees this, you should watch this poem video on labor: https://youtu.be/_R7IcpUScqI

I think the term “slave” means you are subservient to a “master” regardless of the level of abuse. Kind of like how the Bible has described some slave/master relationships as benevolent while others as oppressive. In either case, you don’t have the freedom to do what you truly want or are genuinely skilled at doing. There is less or almost no choice. Hardly any autonomy to change your circumstances. So, our senses and appetites and fears could be our masters. At least, that’s why I have always agonized over my 9–5 or 10–10 jobs. And, if you are a pussy because you don’t want to be subjected to meaningless, ungratifying, and painful work, it means you are not a completely mindless animal. That’s humanity.

Bukowski was more of a man in his sleep, than you ever will be awake. Read that again.