You know you’re doing something right in your life if the Nobel Prize-winning author of 100 Years of Solitude talks to you like a giddy fan boy.

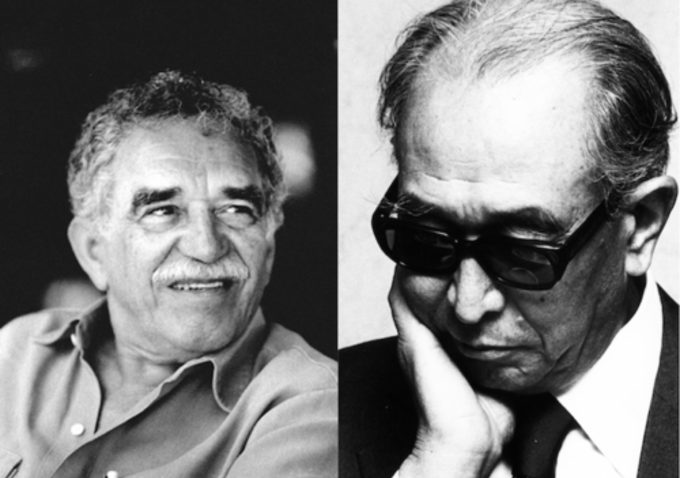

Back in October 1990, Gabriel García Márquez sat down with Akira Kurosawa in Tokyo as the Japanese master director was shooting his penultimate movie Rhapsody in August — the only Kurosawa movie I can think of that features Richard Gere. The six hour interview, which was published in The Los Angeles Times in 1991, spanned a range of topics but the author’s love of the director’s movies was evident all the way through. At one point, while discussing Kurosawa’s 1965 film Red Beard, García Márquez said this: “I have seen it six times in 20 years and I talked about it to my children almost every day until they were able to see it. So not only is it the one among your films best liked by my family and me, but also one of my favorites in the whole history of cinema.”

One natural topic discussed was adapting literature to film. The history of cinema is littered with some truly dreadful adaptations and even more that are simply inert and lifeless. One of the Kurosawa’s true gifts as a filmmaker was turning the written word into a vital, memorable image. In movies like Throne of Blood and Ran, he has proved himself to be arguably the finest adapter of Shakespeare in the history of cinema.

García Márquez: Has your method also been that intuitive when you have adapted Shakespeare or Gorky or Dostoevsky?

Kurosawa: Directors who make films halfway may not realize that it is very difficult to convey literary images to the audience through cinematic images. For instance, in adapting a detective novel in which a body was found next to the railroad tracks, a young director insisted that a certain spot corresponded perfectly with the one in the book. “You are wrong,” I said. “The problem is that you have already read the novel and you know that a body was found next to the tracks. But for the people who have not read it there is nothing special about the place.” That young director was captivated by the magical power of literature without realizing that cinematic images must be expressed in a different way.

García Márquez: Can you remember any image from real life that you consider impossible to express on film?

Kurosawa: Yes. That of a mining town named Ilidachi [sic], where I worked as an assistant director when I was very young. The director had declared at first glance that the atmosphere was magnificent and strange, and that’s the reason we filmed it. But the images showed only a run-of-the-mill town, for they were missing something that was known to us: that the working conditions in (the town) are very dangerous, and that the women and children of the miners live in eternal fear for their safety. When one looks at the village one confuses the landscape with that feeling, and one perceives it as stranger than it actually is. But the camera does not see it with the same eyes.

When Kurosawa and García Márquez talked about Rhapsody in August, the mood of the interview darkened. The film is about one old woman struggling with the horrors of surviving the atomic attack on Nagasaki. When it came out, American critics bristled at the movie because it had the audacity to point out that many Japanese weren’t all that pleased with getting nuked. This is especially the case with Nagasaki. While Hiroshima had numerous factories and therefore could be considered a military target, Nagasaki had none. In fact, on August 9, 1945, the original target for the world’s second nuclear attack was the industrial town of Kita Kyushu. But that town was covered in clouds. So the pilots cast about looking for some place, any place, to bomb. That place proved to Nagasaki.

Below, Kurosawa talks passionately about the legacy of the bombing. Interestingly, García Márquez, who had often been a vociferous critic of American foreign policy, sort of defends America’s actions at the end of the war.

Kurosawa: The full death toll for Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been officially published at 230,000. But in actual fact there were over half a million dead. And even now there are still 2,700 patients at the Atomic Bomb Hospital waiting to die from the after-effects of the radiation after 45 years of agony. In other words, the atomic bomb is still killing Japanese.

García Márquez: The most rational explanation seems to be that the U.S. rushed in to end it with the bomb for fear that the Soviets would take Japan before they did.

Kurosawa: Yes, but why did they do it in a city inhabited only by civilians who had nothing to do with the war? There were military concentrations that were in fact waging war.

García Márquez: Nor did they drop it on the Imperial Palace, which must have been a very vulnerable spot in the heart of Tokyo. And I think that this is all explained by the fact that they wanted to leave the political power and the military power intact in order to carry out a speedy negotiation without having to share the booty with their allies. It’s something no other country has ever experienced in all of human history. Now then: Had Japan surrendered without the atomic bomb, would it be the same Japan it is today?

Kurosawa: It’s hard to say. The people who survived Nagasaki don’t want to remember their experience because the majority of them, in order to survive, had to abandon their parents, their children, their brothers and sisters. They still can’t stop feeling guilty. Afterwards, the U.S. forces that occupied the country for six years influenced by various means the acceleration of forgetfulness, and the Japanese government collaborated with them. I would even be willing to understand all this as part of the inevitable tragedy generated by war. But I think that, at the very least, the country that dropped the bomb should apologize to the Japanese people. Until that happens this drama will not be over.

The whole interview is fascinating. They continue to talk about historical memory, nuclear power and the difficulty of filming rose-eating ants. You can read the entire thing here. It’s well worth you time.

via Thompson on Hollywood H/T Sheerly

Related Content:

Watch Kurosawa’s Rashomon Free Online, the Film That Introduced Japanese Cinema to the West

Andy Warhol Interviews Alfred Hitchcock (1974)

Listen to François Truffaut’s Big, 12-Hour Interview with Alfred Hitchcock (1962)

Akira Kurosawa & Francis Ford Coppola Star in Japanese Whisky Commercials (1980)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

“I have seen it six times in 20 years and I talked about it to my children almost every day until they were able to see it. So not only is it the one among your films best liked by my family and me, but also one of my favorites in the whole history of cinema.”

I feel the exact same about Red Beard. It really is an exceptional work of cinema.

Thanks for sharing this. I am big fan of Kurosawa. My fav film maker.