We’ve long known the internet’s power to facilitate access to the great books (see, for instance, our collection of 600 eBooks free online), but recent projects like the British Library’s Discovering Literature have shown us that it can also help us engage with those great books. The site, says a MetaFilter user who goes under Horace Rumpole, offers “a portal to digitized collections and supporting material. The first installment, Romantics and Victorians, includes work from Austen, the Brontës, Dickens, and Blake, and forthcoming modules will expand coverage of the site to encompass everything from Beowulf to the present day.” For now, if you enjoy classic English Romantic and Victorian novels, prepare to take that enjoyment to a higher level by immersing yourself in all manner of early manuscripts, authors’ papers and personal effects, and related pieces of contemporary media.

If you count yourself a Jane Austen fan, for instance, you can now scroll down her Discovering Literature author page and find “a host of texts” to do with her life, her work, and the intersection between them, “including the opinions — mostly positive — her friends and family had of her novels, copied out by the author (though ‘her immediate family is shown to have disagreed over which of her books was better’).” That comes from The Guardian’s Alison Flood, writing up the site’s collection of not just Austen accoutrements but items from writers like William Wordsworth, Oscar Wilde, and Mary Shelley, “as well as diaries, letters, newspaper clippings from the time and photographs, in an attempt to bring the period to life.”

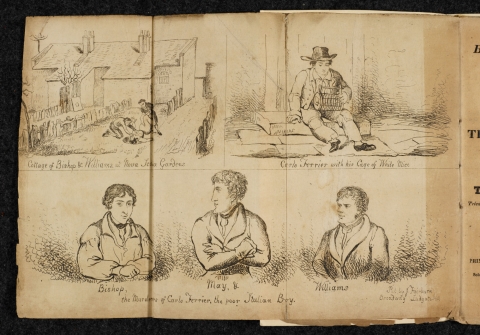

Flood cites “a survey of more than 500 English teachers, which found that 82% believe secondary school students ‘find it hard to identify’ with classic authors” on their classes’ syllabi. In response, Discovering Literature appears to have given special attention to oft-assigned writers like Charles Dickens, whose collection of materials on the site includes a literary sketch published at age 23, color illustrations for both an 1885 and 1911 edition of Oliver Twist (as well as the 1848 review that destroyed his relationship with the book’s previous illustrator), and “The Italian Boy,” an early work of journalism on “a brutal crime that occurred in London in 1831, a ‘copy-cat’ murder following upon those of the infamous Burke and Hare in Edinburgh.” The site’s archives also contain analytical essays on each writer’s body of work, like “Oliver Twist and the Workhouse” and “Status, Rank, and Class in Jane Austen’s Novels” — ideal for when these re-enthused students, previously unable to connect to the Romantic and Victorian eras’ most respected authors, reach grad school.

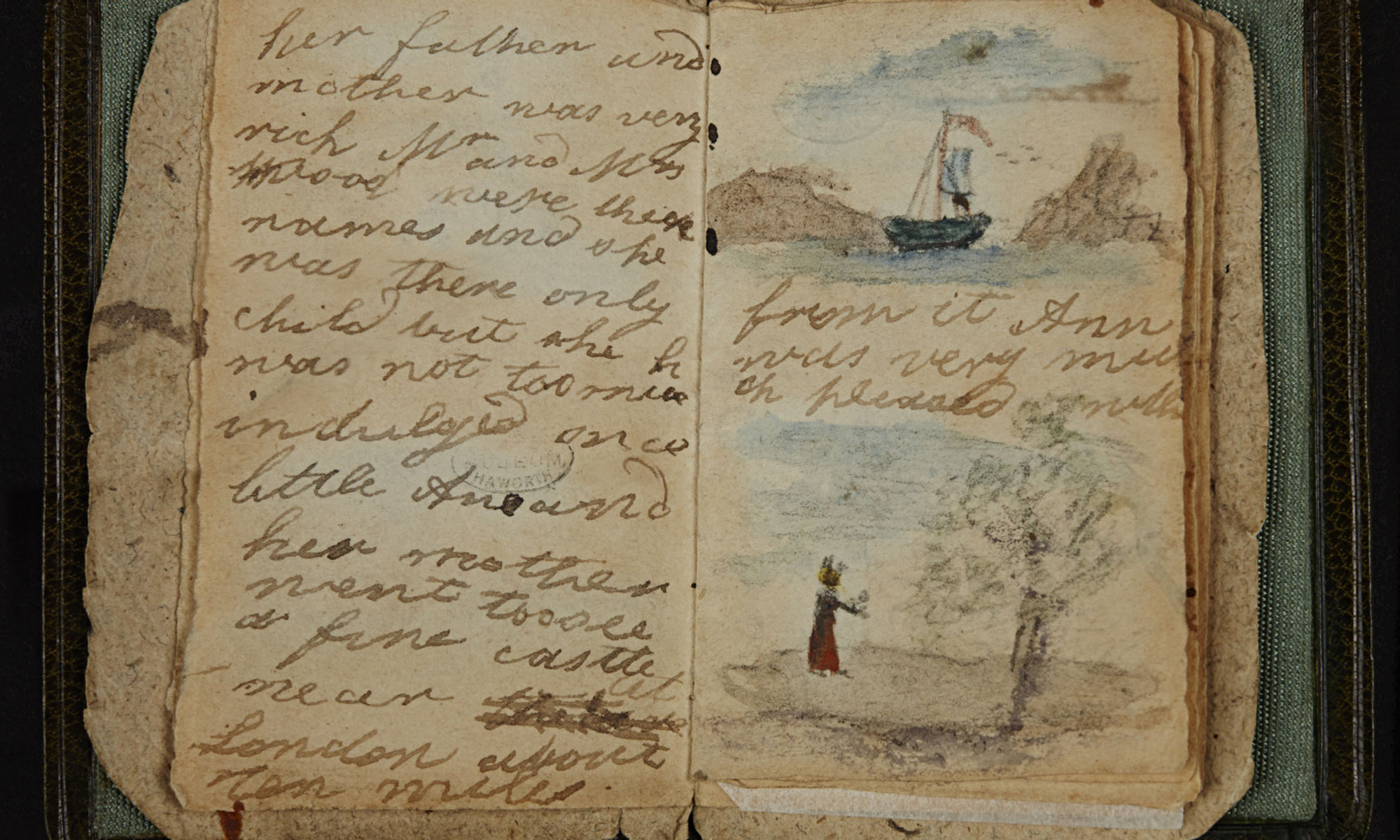

The image at the very top shows the earliest known writings of Charlotte Brontë.

Related Content:

Read Jane Austen’s Manuscripts Online

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Thank you for your contribution to world literacy and scholarship.

What a wonderful resource…I am anxious to begin using it! Thank you!

Fascinating resource! Thanks for sharing the news.