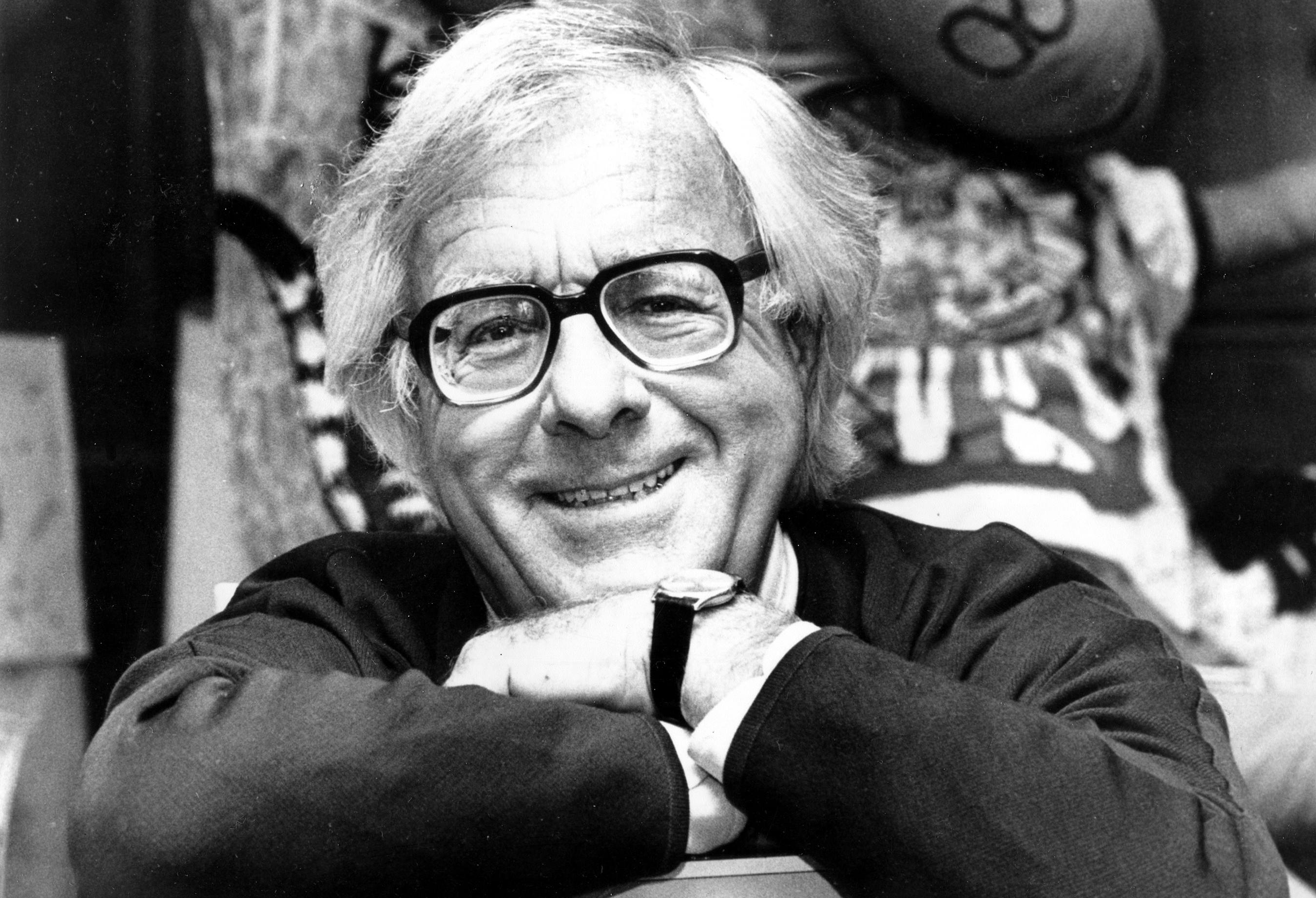

The prolific Ray Bradbury, author of Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles, and many other works both inside and outside the realm of science fiction, apparently suffered no shortage of creativity. Prolific in his fiction writing, he also proved generous in his encouragement of younger writers: we’ve previously featured not just his twelve essential pieces of writing advice but his secret to life and love. He even wrote enough on the subject of writing to constitute an entire book, the collection Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity. In the 1973 title piece, Bradbury, hardly known as a Buddhist, explains his use of the term zen for its “shock value”: “The variety of reactions to it should guarantee me some sort of crowd, if only of curious onlookers, those who come to pity and stay to shout. The old sideshow Medicine Men who traveled about our country used calliope, drum, and Blackfoot Indian, to insure open-mouthed attention. I hope I will be forgiven for using ZEN in much the same way, at least here at the start. For, in the end, you may discover I’m not joking after all.”

He breaks down his own idea of zen in his writing process by first asking himself, “Now while I have you here before my platform, what words shall I whip forth painted in red letters ten feet tall?” He paints the following, and after each we include selections from the essay:

- WORK. “It is, above all, the word about which your career will revolve for a lifetime. Beginning now you should become not its slave, which is too mean a term, but its partner. Once you are really a co-sharer of existence with your work, that word will lose its repellent aspects. [ … ] We often indulge in made work, in false business, to keep from being bored. Or worse still we conceive the idea of working for money. The money becomes the object, the target, the end-all and be-all. Thus work, being important only as a means to that end, degenerates into boredom. Can we wonder then that we hate it so?”

- RELAXATION. “Impossible! you say. How can you work and relax? How can you create and not be a nervous wreck? [ … ] Tenseness results from not knowing or giving up trying to know. Work, giving us experience, results in new confidence and eventually in relaxation. The type of dynamic relaxation again, as in sculpting, where the sculptor does not consciously have to tell his fingers what to do. The surgeon does not tell his scalpel what to do. Nor does the athlete advise his body. Suddenly, a natural rhythm is achieved. The body thinks for itself.”

- DON’T THINK! “The writer who wants to tap the larger truth in himself must reject the temptations of Joyce or Camus or Tennessee Williams, as exhibited in the literary reviews. He must forget the money waiting for him in mass-circulation. He must ask himself, ‘What do I really think of the world, what do I love, fear, hate?’ and begin to pour this on paper. Then, through the emotions, working steadily, over a long period of time, his writing will clarify; he will relax because he thinks right and he will think even righter because he relaxes. The two will become interchangeable. At last he will begin to see himself.”

- FURTHER RELAXATION. “We should not look down on work nor look down on the forty-five out of fifty-two stories written in our first year as failures. To fail is to give up. But you are in the midst of a moving process. Nothing fails then. All goes on. Work is done. If good, you learn from it. If bad, you learn even more. Work done and behind you is a lesson to be studied. There is no failure unless one stops. Not to work is to cease, tighten up, become nervous and therefore destructive of the creative process. [ … ] Isn’t it obvious by now that the more we talk of work, the closer we come to Relaxation.”

- “Have I sounded like a cultist of some sort? A yogi feeding on kumquats, grapenuts and almonds here beneath the banyan tree? Let me assure you I speak of all these things only because they have worked for me for fifty years. And I think they might work for you. The true test is in the doing. Be pragmatic, then. If you’re not happy with the way your writing has gone, you might give my method a try. If you do, I think you might easily find a new definition for Work. And the word is LOVE.”

You can read much more about Bradbury’s method of working, relaxing, not thinking, and relaxing further still — and his thoughts on the joy of writing, keeping the muse fed, establishing a thousand-or-two-words-a-day habit, and “how to climb the tree of life, throw rocks at yourself, and get down without breaking your bones or your spirit” — in the book, Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity.

Related Content:

Ray Bradbury Gives 12 Pieces of Writing Advice to Young Authors (2001)

The Secret of Life and Love, According to Ray Bradbury (1968)

Ray Bradbury: Literature is the Safety Valve of Civilization

Ray Bradbury: “The Things That You Love Should Be Things That You Do.” “Books Teach Us That”

Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer 1963 Film Captures the Paradoxical Late Sci-Fi Author

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Love lief

Love art

Write, write, write!

What an amazing mind! Such an insightful perspective with such a wonderful talent for insipring young writers! You are missed!