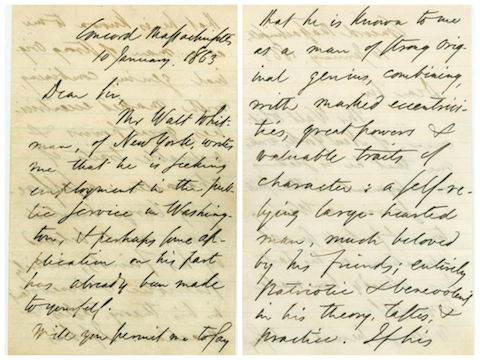

While we often recommend Letters of Note for the hits of history’s most illuminating pieces of incidental correspondence, do consider also making a regular visits to Slate’s history blog The Vault. There you’ll find such written artifacts as the one pictured in part above, astutely written up by occasional Open Culture contributor Rebecca Onion: “In 1863, as he considered seeking a government clerkship, Walt Whitman asked his friend and advocate Ralph Waldo Emerson for a letter of recommendation. Emerson, for decades a respected name in American letters, knew the secretaries of state and treasury personally, and Whitman hoped that a note from him would help the younger poet secure steady employment in Washington.” This note runs, in a transcript from the Walt Whitman archive, as follows:

Concord Massachusetts

10 January 2, 1863Dear Sir,

Mr Walt Whitman, of New York, writes me that he is seeking employment in the public service in Washington, & perhaps some application on his part has already been made to yourself. Will you permit me to say that he is known to me as a man of strong original genius, combining, with marked eccentricities, great powers & valuable traits of character: a self-relying large-hearted man, much beloved by his friends; entirely patriotic & benevolent in his theory, tastes, & practice. If his writings are in certain points open to criticism, they show extraordinary power, & are more deeply American, democratic, & in the interest of political liberty, than those of any other poet.

A man of his talents & dispositions will quickly make himself useful, and, if the government has work that he can do, I think it may easily find that it has called to its side more valuable aid than it bargained for.

With entire respect,

Your obedient servant,

R. W. Emerson.

Hon Salmon P. Chase, | Secretary of the Treasury.

Any of us, I feel certain, would love having such an eloquently praise-filled letter of recommendation sent on our behalf by a friend, a teacher, a former employer, or a pillar of American Transcendentalism. But even with that, the author of Leaves of Grass didn’t find the road to a day gig particularly smooth — in large part, of course, because of having written Leaves of Grass. Whitman, whose “reputation preceded him in job interviews, reported that Salmon Chase, the secretary of the treasury and addressee of this letter, was vehemently against the idea of employing the author of Leaves, a book that celebrated open sexuality in a way that Chase found distasteful.” He would even get fired from another job specifically “because of objections to his poetry.” Well, they can’t say Emerson didn’t warn them about Whitman’s “marked eccentricities” — such as his tendency to write some of the most enduring verse in American history.

via The Vault

Related Content:

Mark Twain Writes a Rapturous Letter to Walt Whitman on the Poet’s 70th Birthday (1889)

Hear Walt Whitman (Maybe) Reading the First Four Lines of His Poem, “America” (1890)

Find works by Whitman and Emerson in our twin collections: 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free and 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

God bless Emerson for that letter.