One of the great polymaths of the 19th century, Lewis Carroll (pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) —mathematician, logician, author, poet, Anglican cleric—took to the new medium of photography with the same alacrity he applied to all of his pursuits. Though he may be described as a hobbyist in the sense that he never pursued the art professionally, he nonetheless “became a master of the medium, boasting a portfolio of roughly 3,000 images and his very own studio.”

So says a recent article by Gannon Burgett on Carroll’s “24-year career as a photographer,” during which he made a number of portraits, including one of then-poet laureate of England Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His subjects also included “landscapes, dolls, dogs, statues, paintings, trees and even skeletons.”

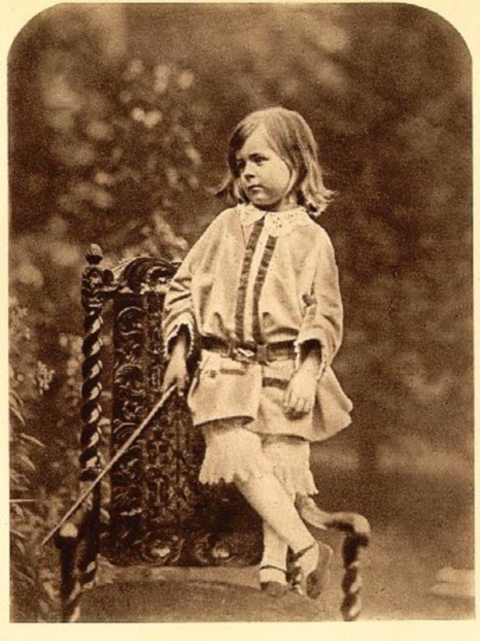

Carroll excelled at a developing method called the wet collodion process, which replaced the daguerreotype as the primary means of photographic image-making. This process seems to have been something like painting in oils, requiring a great deal of dexterity and chemical know-how, and similarly subject to decay when done improperly. Carroll particularly valued this method for its difficulty (he described it in detail in some lines added to a poem called “Hiawatha’s Photographing”)—so much so that once a dry developing process came into being, he abandoned the medium altogether, complaining that it became so easy anyone could do it. Carroll’s obsessive focus on process mirrored an obsession with his favorite photographic subjects, young children, including Tennyson’s son Hallam (above). Most famously, Carroll obsessively photographed the young Alice Liddell (top and below as “The Queen of May”), daughter of family friend Henry George Liddell and inspiration for Carroll’s most famous fictional character.

Many of Carroll’s photographs of Alice and other children can seem downright prurient to our eyes. As Carroll’s biographer Jenny Woolf writes in a 2010 essay for the Smithsonian, “of the approximately 3,000 photographs Dodgson made in his life, just over half are of children—30 of whom are depicted nude or semi-nude.”

Some of his portraits—even those in which the model is clothed—might shock 2010 sensibilities, but by Victorian standards they were… well, rather conventional. Photographs of nude children sometimes appeared on postcards or birthday cards, and nude portraits—skillfully done—were praised as art studies […]. Victorians saw childhood as a state of grace; even nude photographs of children were considered pictures of innocence itself.

Woolf admits that Carroll’s interest, as scholars have speculated for decades, may have been less than innocent, prompting Vladimir Nabokov to propose “a pathetic affinity” between Carroll and the narrator of Lolita. The evidence for Carroll’s possible pedophilia is highly suggestive but hardly conclusive. Burgett summarizes the claims as only speculative at best: “The entire controversy is an almost century-long debate, and one that doesn’t seem to be making any major progress in either direction.” In a Slate review of Woolf’s Lewis Carroll biography, Seth Lerer also acknowledges the controversy, but reads the photographs of Alice, her sisters, and friends as representative of larger trends, as “brilliant testimonies to the taste, the sentiment, and perhaps the sexuality of mid-Victorian England.”

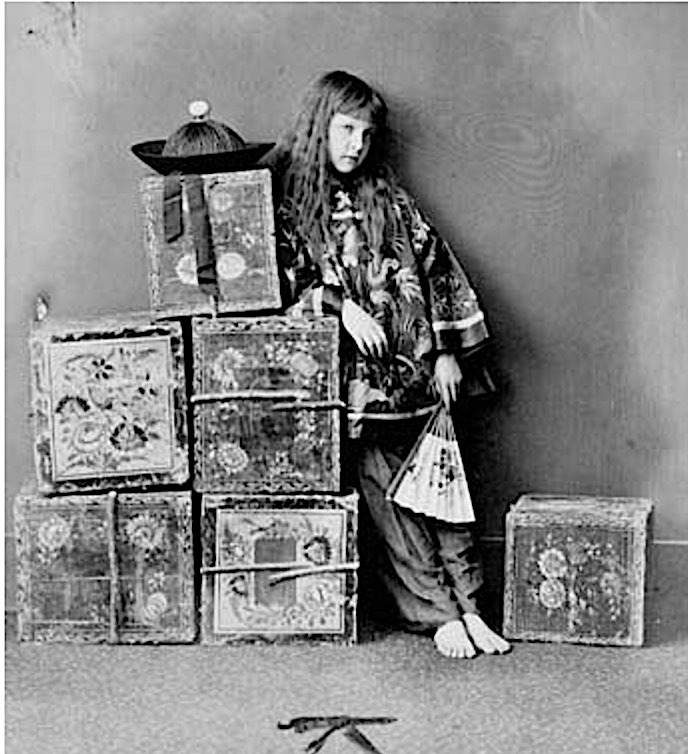

A great part of this Victorian sensibility consists of the “recognition that all life involves role-playing,” hence the recurring photos of the girls in dress-up—as figures from myth and literature and exotic Orientalist characters, such as the photo above of Alice and her sister Lorina as “Chinamen.” “These are the tableaux of Victorian melodrama,” writes Lerer, “images on stage-sets of the imagination.” We see another of Carroll’s favorite photographic subjects, Alexandra “Xie” Kitchin, daughter of a colleague, also given the Orientalist treatment below, posed as an off-duty tea merchant.

Carroll’s carefully staged child photographs are very much like those of other photographers of the period like Mary Cowden Clarke and Julia Margaret Cameron, who also photographed Alice Liddell, even into her adulthood. Cameron’s photographs also included child nudes, to a similar effect as Carroll’s—the depiction of a “state of grace” in which children appear as nymphs, “gypsies” or other such types supposedly belonging to Edenic worlds untouched by adult cares. Given the context Woolf, Lerer and others provide, it’s reasonable to view Carroll’s child photography as consistent with the tastes of the day. (Though no one suggests this as an alibi for Carroll’s possibly troubling proclivities.)

As it stands, the photographs of Alice and other children open a fascinating, if sometimes discomfiting, window on an age that viewed childhood very differently than our own. They also give us a view of Carroll’s strange inner world, one not unlike the unsettling fantasy realm of 20th century folk artist Henry Darger. Unlike Darger, Carroll’s work brought him widespread fame in his lifetime, but like that reclusive figure, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass was a shy, introspective man whose imaginative landscape possessed a logic all its own, charged with magic, threat, and longing for lost childhood innocence.

See a galleries of Carroll’s photographs of Alice and other children here and here, and see this site for more general info on Carroll’s photography.

Related Content:

See Salvador Dali’s Illustrations for the 1969 Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Free Audio: Alice In Wonderland Read by Cory Doctorow

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

“Woolf admits that Carroll’s interest, as scholars have speculated for decades, may have been less than innocent”

If you truly think she “admits” that, then you completely misinterpreted what she wrote and you need to read closer. Woolf is one the major biographers AGAINST the pedophile theory.

Other than that, fair article and you seem to understand the Victorian Child Cult better than other writers have.

Well, I’m not from the Victorian Age, and I must say that a book of Lewis Carroll’s photographs discomfited me somewhat. It’s curious how certain aspects of an earlier era can run counter to our general perception (or learning) about them.

The writer of this article Wolfe is pure disgust! I wonder if your child gets molested will you have doubts if you find naked photos or maybe you will be a participant!!! Shameful…Victorian times were about purity and grown

woman’s reputation was extremely important a naked child was not the sign of the times!!! You are lying and anyone that has studied that time period is fully aware.

Does this look innocent to you?

https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2015/01/carroll-and-alice-kissing.jpg

That ‘kissing’ photo is a fake. Do some research

Teresa McKimmey is right. https://snrk.de/page_constructing-carroll

Ari, attacking Wolfe ad hominem like that is disgusting. Victorian times (and of course not only those times) also were about displaying “purity” as a means to deal with “impurity”. Each era has its ways of reputation management. And child labour was one of the signs of those times. As almost all eras, this one had shiny sides as well as dark sides.

Furthermore, once new media ar available, it takes time to define the do’s and dont’s for using them. That applied and still applies to photography then as much as it applies today to what you can post or shouldn’t post in the internet.

She was truly beautiful but Lewis took it too far. He should have been her protector.

What did he not protect her from? There is never any evidence he ever hurt her.

The Victorian Child Cult still exists, right down to the complete denial of children’s sexuality (a well-documented scientific fact) and the obligatory disapproval of Carroll’s “possibly troubling proclivities.” This is still a realm where sexuality can only be considered dirty, shameful, perverse etc etc. A shame for Carroll and people like him that we’ve yet to progress in this area.