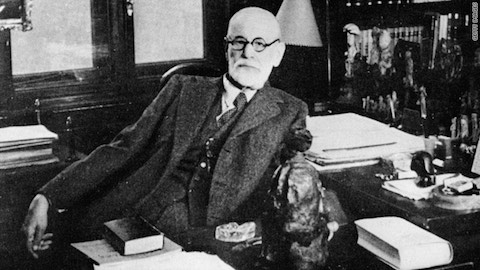

As David Bowie had his cocaine period, so too did Sigmund Freud, beginning in 1894 and lasting at least two years. Unlike the rock star, the doctor was just at the beginning of his career, “a nervous fellow” of 28 “who wanted to make good,” says Howard Markel, author of An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. Markel tells Ira Flatow in the NPR Science Friday episode below that Freud “knew if he was going to get a professorship, he would have to discover something great.”

Freud’s experiments with the drug led to the publication of a well-regarded paper called “Über Coca,” which he described as “a song of praise to this magical substance” in a “pretty racy” letter to his then-fiancé Martha Bernays. (He also promised she would be unable to resist the advances of: “a big, wild man who has cocaine in his body.”) Two years later, his health suffering, Freud apparently stopped all use of the drug and rarely mentioned it again.

[T]he accomplished young phsyiologist Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, whose morphine addiction Freud had tried to treat with cocaine, with disastrous results. As Freud wrote almost three decades later, “the study on coca was an allotrion” — an idle pursuit that distracts from serious responsibilities — “which I was eager to conclude.”

The drug was at the time touted as a panacea, and Fleischl-Marxow, Markel says, was “the first addict in Europe to be treated with this new therapeutic.” Freud also used himself as a test subject, unaware of the addictive properties of his cure for his friend’s addiction and his own depression and reticence.

While Freud conducted his experiments, another medical pioneer—American surgeon William Halsted, one of Johns Hopkins “four founding physicians”—simultaneously found uses for the drug in his practice. Freud and Halsted never met and worked completely independently in entirely different fields, says Markel in the news segment above, but “their lives were braided together by a fascination with cocaine,” as addicts, and as readers and writers of “several medical papers about the latest, newest miracle drug of their era, 1894.” Halstead is responsible for many of the modern surgical techniques without which the prospect of surgery by today’s standards is unimaginable —the proper handling of exposed tissue, operating in aseptic environments, and surgical gloves. He injected patients with cocaine to numb regions of their body, allowing him to operate without rendering them unconscious.

Halsted, too, used himself as a guinea pig. “No doctor knew at this point,” says Markel above, “of the terrible addictive effects of cocaine” before Freud and Halsted’s experiments. Both men irrevocably changed their fields and almost destroyed their own lives in the process (see a short documentary on Halsted’s medical advances below). In Freud’s case, much of the work of psychoanalysis has come to be seen as pseudoscience—his work on dreams significantly so, as Markel says above: “Cocaine haunts the pages of the Interpretation of Dreams. The model dream is a cocaine dream.” The “talking cure,” however, engendered by the “loosening of the tongue” Freud experienced while on cocaine, endures as, of course, do Halsted’s innovations.

Related Content:

Freud’s Thought Explained in Yale Psych Course (Find Full Course on our List of 875 Free Online Courses)

Sigmund Freud Speaks: The Only Known Recording of His Voice, 1938

Sigmund Freud’s Home Movies: A Rare Glimpse of His Private Life

Jean-Paul Sartre Writes a Script for John Huston’s Film on Freud (1958)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“In Freud’s case, much of the work of psychoanalysis has come to be seen as pseudoscience.”

Medicine is not a science. Of course it is based on scientific research, but it is not a science. It is practice or an art. Freud thought it might be possible to base his ideas on neuroscientific research (a very faint hope), which was his specialization early in this career, but psychoanalysis itself is a practice. You might claim that it a ‘pseudo-practice’ but that is something very different from a ‘pseudo-science’.

Cocaine in all its glamour could not entice a wise intelligent man past the brink of no return. It is interesting to see how the man recognized the line of addiction, and was able to consciously make decisions to avoid continuing down it to a path of destruction as implied here: ” an idle pursuit that distracts from serious responsibilities — “which I was eager to conclude.” Beginning with a traumatic event which most addictions do flourish in such environments, it is another confirmation that the problem is not the drug use, but rather the cause of it and the decision making after it. More treatment facilities are needed that focus on action based real life recovery model like House of Recovery, that looks past the surface and addresses the real problems, where the cure is.

Psychoanalysis is not a pseudo science. It is an effective method of treatment. People who are candidates for psychoanalysis are people who have significant problems in applying themselves and their intellect to meaningful work. They may also have longstanding issues in their relationships with others–including love relationships.

Currently, people are not accepted for psychoanalysis until they have been in psychotherapy first.

The patient meets with the analyst 4–5 times per week in 45 minute sessions. The average length of an analysis is 4 years.

People who go into analysis are usually educated, and psychologically minded. They have suffered for a long time, and lesser treatments have failed. These days, medication can be used with analytic patients–which has only been true for the last 20 years or so. This means a broader range of people can be seen in analysis–which includes sicker ones.

There are differing opinions on this, but psychoanalysis is a more intense, deeper therapy–but similar issues are also discussed in psychodynamic psychotherapy.

The average number of sessions spent in psychotherapy is 10. Obviously, most people are not interested in a psychoanalysis either because it doesn’t apply, or because it requires too much emotional and/or financial commitment.

Psychoanalysis has never been seen as a pseudoscience. As a matter of fact, you walk into any university upper level psych class, and they will speak of just how intuitively correct Sigmund Freud was.

As a psychology student, I am very concerned about the number of people responding that Freud’s ideas are an accurate science. While he had some valid concepts, generally when someone in a psychology classroom tries to describe someone’s behaviors as motivated by the Oedipus Complex, penis envy, or the Death Drive, in all but the most radical of cases it is met with laughter.

@Bill, I don’t see many folks advocating that psychoanalysis is a science above; some folks are distinguishing science from art, and a couple mention the utility of the ideas themselves, but I don’t see any argument that psychoanalysis is a science. Of course, the distinction itself is heavily ideological. From your tone, I’d say you lean pretty hard toward positive science, and you feel like psychology sits squarely in that field (while many other positive scientists consider psychology, itself, rather problematic, and better categorized as social science, much like economics wherewith a similar struggle ensues, as does the broader struggle between the positive and social sciences themselves). Insofar as you touch upon Edward’s comment, I think, again, you could read a bit more closely: calling ideas intuitive is not to say that they can be transposed directly from their context of enunciation into the contemporary setting of an university lecture hall or seminar room. Indeed, the variance amongst universities in general, and on the question of psychoanalysis in particular, would preclude a unitary statement on the condition of that discursive formation contemporaneously. Without delimiting the field more than even the space of the university, one can scarcely offer a productive judgement on whether psychoanalysis is a relevant and productive epistemological apparatus, for whom, and oriented towards what goals (what would constitute productivity, here, in other words). Part of being a student is entering into a debate recognizing the differences of perspective, without succumbing to the desire to protect and defend at the slightest whiff of challenge…

You might be interested in our new book and Analysis of psychoanalysis with Freud’s first publicized case, little Hans.

“Freud’s Fallacy,

Baby Hans–Carefully.”

By Dr Clifford Brickman

and Rabbi Jay Brickman

This analytic dialogue also leads into an enhancement and advancement in Self psychology — the organic Self.