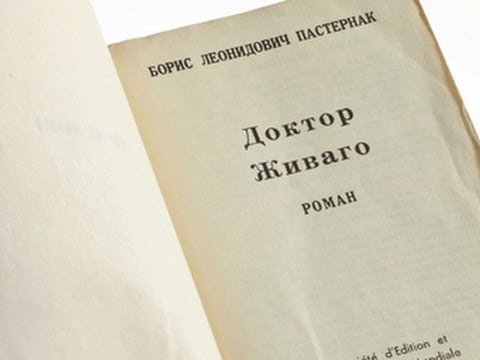

Humanity has long pondered the relative might of the pen and the sword. While one time-worn aphorism does grant the advantage to the pen, most of us have entertained doubts: the sword, metaphorically or literally, seems to have won out across an awfully wide swath of history. Still, the pen has scored some impressive victories, some even in living memory. Take, for example, the CIA’s recently revealed use of Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago as a propaganda weapon. Repressed in Pasternak’s native Russia, the book first appeared in Italy in 1957. The following year, the British suggested to America’s Central Intelligence Agency that the book stood a decent chance of winning hearts and minds behind the Iron Curtain — if, of course, they could get a few copies in there. A CIA memo sent across its own Soviet Russia Division subsequently pronounced Doctor Zhivago as possessed of “great propaganda value, not only for its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also for the circumstances of its publication. We have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country in his own language for his own people to read.”

That evaluation comes from one of the over 130 declassified documents used by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée in their brand new history of this act of real-life literary espionage, The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book. You can read an in-depth article on some of the events involved in this operation — the CIA’s printing of both hardcover and miniature paperback Russian-language editions, the not-so-clandestine distribution of copies at 1958’s Brussels Universal and International Exposition, the CIA’s unexpected alliance with the Vatican in this mission, the inept probing by Soviet “researchers” — at the Washington Post.

You can also watch a CBS This Morning clip on the book just above. Dramatic though this “Zhivago Affair” sounds, it came as neither the first nor last American use of culture as a means of destabilizing the Soviet Union. We’ve even previously featured two others: secretly-funded abstract expressionist painting, and Louis Armstrong’s 1965 East Berlin and Budapest concerts. Cold War America may have had the sword, in the form of its vast nuclear arsenal, polished and ready, but clearly it retained a certain regard for the pen — and brush, and trumpet — as well.

Related Content:

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965)

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply