I admit it: I still don’t understand sentence diagramming. Though as a middle schooler I dutifully, if grudgingly, submitted to that classic English classroom exercise, the practice didn’t stick, nor did whatever habit of composition it meant to convey. Some of my teachers tried to make sentence diagramming interesting, but they could only do so much. They could only do so much, that is, without Pop Chart Lab’s “A Diagrammatical Dissertation on Opening Lines of Notable Novels,” a poster that “diagrams 25 famous opening lines from revered works of fiction according to the dictates of the classic Reed-Kellogg system,” with each and every graphic “parsing classical prose by parts of speech and offering a partitioned, color-coded picto-grammatical representation of some of the most famous first words in literary history.”

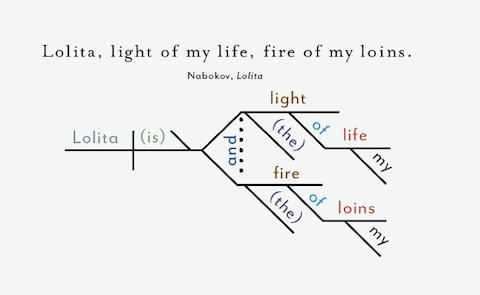

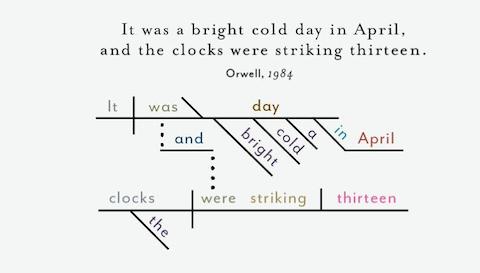

At the top of the post, we have the poster’s diagram of Humbert Humbert’s famous first words, by way of Vladimir Nabokov, in Lolita: “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins.” That immortal sentence may always have struck you as incomplete — doesn’t it need a verb? — but hey, it diagrams, at least with the addition of the implicit (is) and a couple implicit (the)s. Follow the branches and you find the words’ concealed complexity visually revealed. Just above, you’ll see diagrammed a more traditional opening sentence from George Orwell, a much more plainspoken writer. “It was a bright cold day in April,” goes the first line of 1984, “and the clocks were striking thirteen” — a more linguistically involved description, as you can see, than it may at first seem. Fifteen years after the specter of Reed-Kellogg darkened my desk — in which time I’ve made writing my career — I still can’t claim the ability to produce properly diagrammed sentences for myself. But I like to think that I can appreciate them, especially when they show me the workings of a sufficiently great sentence.

See more famous opening sentences from Pop Chart Lab’s poster (and purchase your own copy) here.

Related Content:

George Orwell’s 1984: Free eBook, Audio Book & Study Resources

The History of the English Language in Ten Animated Minutes

Learn Languages for Free: Spanish, English, Chinese & 37 Other Languages

David Foster Wallace Breaks Down Five Common Word Usage Mistakes in English

Nabokov Reads Lolita, Names the Great Books of the 20th Century

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, aesthetics, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

I’d like to see the opening sentence from I, CLAUDIUS diagrammed. That would be a complicated mess:

“I, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus This-that-and-the-other (for I shall not trouble you yet with all my titles), who was once, and not so long ago either, known to my friends and relatives and associates as ‘Claudius the Idiot’, or ‘That Claudius’, or ‘Claudius the Stammerer’, or ‘Clau-Clau-Claudius’, or at best as ‘Poor Uncle Claudius’ [a marginal note here adds the date ‘A.D. 41’], am now about to write this strange history of my life; starting from my earliest childhood and continuing year by year until I reach the fateful point of change where, some eight years ago, at the age of fifty-one, I suddenly found myself caught in what I may call the ‘golden predicament’ from which I have never since become disentangled.”

Cheers!