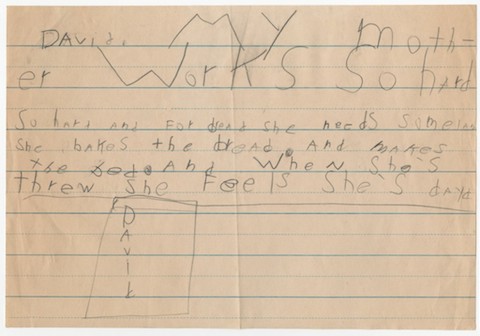

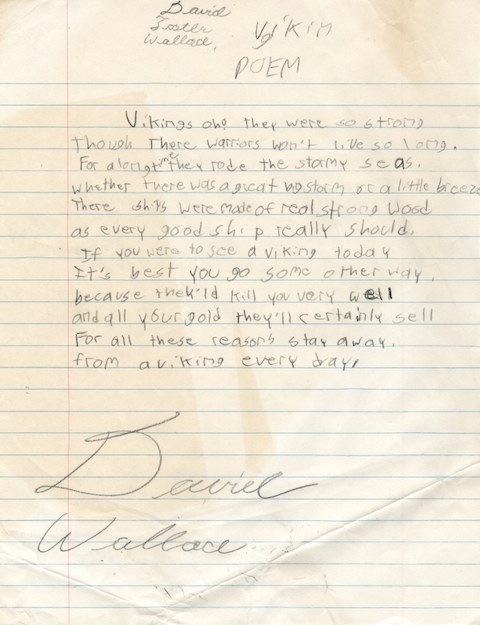

Some readers discover David Foster Wallace through his fiction, and others discover him through his essays. (Find 30 Free Stories & Essays by DFW here.) Now that the publishing industry has spent more than five years putting out everything of the late writer’s leftover material they can reasonably turn into books, new DFW fans may arrive through more forms still: his interviews, Kenyon commencement speech, philosophy thesis, etc.. And though he produced too few of them to appear collected between covers, Wallace once wrote poems as well, though judging by the handwriting of the two shown here, he seems to have both started down and abandoned that particular literary avenue in childhood. Still, that very quality — and the opportunity it holds out to see the linguistic formation of a man later regarded as a prose genius — makes them all the more intriguing. First, we have the untitled poem above, a sympathetic paean to the labors of motherhood:

My mother works so hard

And for bread she needs some lard.

She bakes the bread. And makes the bed.

And when she’s threw

She feels she’s dayd.

Second, we have ”Viking Song”, which he probably wrote later. (The Harry Ransom Center at UT-Austin, where the text resides, believes he was 6 or 7 when he wrote the poem.)

Vikings oh! They were so strong

Though there warriors won’t live so long.

For a long time they rode the stormy seas.

Whether there was a great big storm or a little breeze.

There ships were made of real strong wood

As every good ship really should.

If you were to see a Viking today

It’s best you go some other way.

Because they’d kill you very well

And all your gold they’ll certainly sell

For all these reasons stay away

From a Viking every day.

Though not what we would call mature works, these two poems still offer much of interest to the dedicated DFW exegete. “Note Wallace’s uncommon phrasing in ‘so hard and for bread,’ ” writes Justine Tal Goldberg of the first. “I can’t think of a single child who would opt for this phrasing over, say, a more simple ‘so hard to make bread,’ ” a choice that demonstrates he “was already exhibiting the masterful grasp of language for which he would later become famous.” Alex Balk at The Awl calls “Viking Poem” “ ‘charming and tragic,” adding that “the obvious enthusiasm with which he wrote it makes me reflect on the joys of childhood that we tend to forget.” Wallace’s biographer D.T. Max goes into more depth at the New Yorker, identifying “moments in these poems that herald (or just accidentally foreshadow?) the mature David’s American plainsong voice.” I’ve heard it asserted that every child has a natural capacity for poetry, but the young Wallace, preternaturally perceptive even then, must have soon realized that his textual strengths resided elsewhere.

Related Content:

David Foster Wallace’s Love of Language Revealed by the Books in His Personal Library

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

David Foster Wallace: The Big, Uncut Interview (2003)

David Foster Wallace’s 1994 Syllabus

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.

Shouldn’t that first line read:

My mother works so hard, so hard

Better meter. Seems like he knew it!