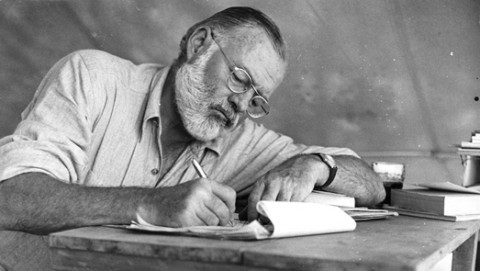

I confess, I prefer Faulkner to Hemingway and see nothing wrong with long, complex sentences when they are well-constructed. But in most non-Faulkner writing, they are not. Stream of consciousness is a deliberate effect of carefully edited prose, not the unrevised slop of a first draft. In my days as a writing teacher, I’ve read my share of the latter. The English teacher’s guide for paring down unruly writing resembles a new online app called “Hemingway,” which examines writing and grades it on a color-coded difficulty scale. “Hemingway” suggests using simpler diction, editing out adverbs in favor of stronger verbs, and eliminating passive voice. It promises to make your writing like that of the famous American minimalist, “strong and clear.”

Of course I couldn’t resist running the above paragraph through Hemingway. It received a score of 11—merely “O.K.” It suggested that I change the passive in sentence one and remove “carefully” from the fourth sentence (I declined), and it identified “unruly” as an adverb (it is not). Like all forms of advice, it pays to use your own judgment before applying wholesale. Nevertheless, the suggestion to streamline and simplify for clarity’s sake is a general rule worth heeding more often than not. Brothers Adam and Ben Long, creators of the app, realized that their “sentences often grow long to the point that they became difficult to read.” It happens to everyone, amateur and professional alike. The app suggests writing that scores a Grade 10 or below is “bold and clear.” Writing above this measure is “hard” or “very hard” to read. Which prompts the inevitable question: How does Hemingway himself score in the Hemingway app?

In a blog post yesterday for The New Yorker, Ian Crouch ran a few of the master’s passages through the online editing tool (a concept akin to John Malkovich entering John Malkovich’s head). The opening paragraph of “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” received a score of 15. Hemingway’s description of Romero the bullfighter from The Sun Also Rises also “breaks several of the Hemingway rules” with its use of passive voice and extraneous adverbs. Does this mean even Hemingway falls short of the ideal? Or only that writing rules exist to be broken? Both, perhaps, and neither. Style is as elusive as grammar is constricting, and both are mastered only through endless practice. Will “Hemingway” turn you into Hemingway? No. Will it make you a better writer? Maybe. But only, I’d suggest, inasmuch as you learn when to accept and when to ignore its advice.

Related Content:

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Jack Kerouac Lists 9 Essentials for Writing Spontaneous Prose

Crime Writer Elmore Leonard Provides 13 Writing Tips for Aspiring Writers

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“Well-constructed” is an adjective, so I don’t see the passive in sentence one.

And Mark Liberman had similar results applying Hemingway to Hemingway: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=10416

Right you are, Steve. Originally, without the hyphen, “constructed” read as a past participle.

Thanks for the link!

Passives, adverbs, and complex constructions are actually quite useful, which is probably why they exist.

Who needs Hemingway? We have hundreds of writers that can give that Hemingway feeling.

I can’t wait to give my prose, a professional appeal!

Hemingway App also works as an offline version. Just save the webpage. Be sure to use “Web Page, complete” in Firefox. “Save as Word Doc” will not work, but otherwise it works fine. (Readability: Grade 5, Good)

Fully engage the proverbial B.S. detector, you mean? Ernest would approve.

http://orwellapp.com is a similar idea to HeminwayApp but with a bit more functionality.

hello

please send me one free edition of heminwayapp