When I was young, I decided that I would learn how to pick locks. If countless intrepid TV heroes could dismantle a pair of handcuffs with nothing but a hastily swiped paperclip, why couldn’t I? The process, it turns out, was quite easy: I practiced on an old, lockable diskette cabinet, and quickly figured out how to crack the lock’s mechanism using two paperclip halves. This allowed me to proclaim that I was an expert lock picker to my friends, and that, really, the whole thing was an elementary procedure.

Although, as the astute reader would surmise, I knew next to nothing about lock picking, I was right on one count: it’s easy. Or, at least, so notes the MIT Guide to Lock Picking, written by the mysterious Ted The Tool. This primer was first published in 1987 and has been floating around various websites for the past two decades. And it’s still considered an essential introduction to the art of picking locks. It begins by outlining lock terminology:

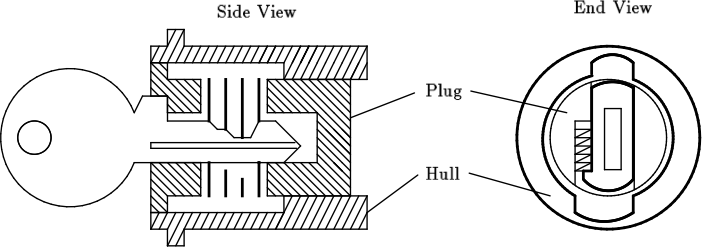

The key is inserted into the keyway of the plug. The protrusions on the side of the keyway are called wards. Wards restrict the set of keys that can be inserted into the plug. The plug is a cylinder which can rotate when the proper key is fully inserted. The non-rotating part of the lock is called the hull. The first pin touched by the key is called pin one. The remaining pins are numbered increasingly toward the rear of the lock.

The proper key lifts each pin pair until the gap between the key pin and the driver pin reaches the sheer line. When all the pins are in this position, the plug can rotate and the lock can be opened. An incorrect key will leave some of the pins protruding between the hull and the plug, and these pins will prevent the plug from rotating.

Over its 50 pages, the guide explains the flatland and pin column lock models, and lays out the theory behind opening them. It also includes guidelines on making lock picking tools, legal information, and numerous pieces of practical advice. Most useful? It contains numerous exercises, and stresses the importance of doing your lock picking homework:

“Anyone can learn how to open desk and filing cabinet locks, but the ability to open most locks in under thirty seconds is a skill that requires practice.”

lia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Learn How Richard Feynman Cracked the Safes with Atomic Secrets at Los Alamos

MIT Teaches You How to Speak Italian & Cook Italian Cuisine All at Once (Free Online Course)

The Enigma Machine: How Alan Turing Helped Break the Unbreakable Nazi Code

Interesting column about this fabulous art. I read the MIT guide several times and really helped me to learn the essential skills. On http://www.lockpickcenter.com there is also good information about which lockpicks to use and how they work.

Great article! As with any skill supplemental resources on how to pick a lock are useful. Another great article that I have found very useful is Art Of Lockpicking: How to pick a lock which can be found here: http://art-of-lockpicking.com/how-to-pick-a-lock-guide/