The work of Hannah Arendt has been in the press recently for two reasons in particular: first, the 50th anniversary of her book Eichmann in Jerusalem, published in 1963 from reports she filed for The New Yorker on the 1961 trial of the archetypal Nazi bureaucrat. Then there is Margarethe von Trotta’s 2012 biopic Hannah Arendt, starring German actress Barbara Sukowa as the German Jewish philosopher. Recent coverage of the book and the film have focused on Arendt’s reputation as a philosophical journalist most closely identified with the famous descriptive phrase “the banality of evil,” a comment on Adolf Eichmann as an exemplar of genocidal murderers who, as the well-worn defense goes, were “just following orders.”

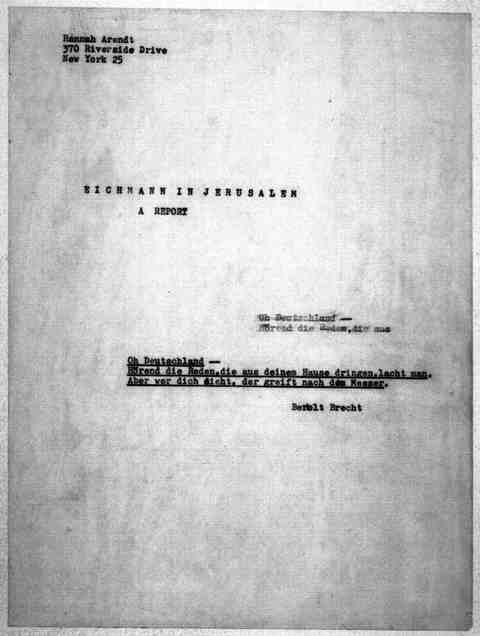

Arendt scholar Roger Berkowitz argues that this reading of Arendt’s book is a profound misreading. Eichmann in Jerusalem was divisive, setting critics against each other in efforts to vindicate or castigate its author. The controversy, however, at the time of publication and again in the recent re-evaluation, has the unfortunate effect of obscuring the breadth of Arendt’s philosophical thinking apart from Eichmann and Nazism. Those interested in connecting with Arendt’s life, scholarship, and philosophical insight can find a wealth of archival materials online from the collections of Bard College and the Library of Congress. Today, we highlight several items in those collections that may be of interest, including the Library of Congress’s scanned copy of the final typescript of Eichmann in Jerusalem.

First, directly above, hear Arendt’s speech “Power & Violence.” The lecture re-iterates ideas Arendt expressed more fully in a lengthy 1969 essay published by the New York Review of Books as “Reflections on Violence” and as a book titled On Violence. In the lecture and the essay, Arendt references the work of thinkers like Friedrich Engels and, especially, Frantz Fanon in a critical discussion of the roles racism and ideology play in state violence.

That same year Arendt delivered a series of lectures for a Spring semester course at The New School for Social Research called “Philosophy and Politics: What is Political Philosophy.” This fascinating investigation grapples not only with political philosophy, but philosophy in general as a meaningful activity. You can view the full typescripts of her course lectures here.

The Library of Congress has also digitized much of Arendt’s correspondence and uploaded images of her letters, including some to and from such well-known figures as W.H. Auden, Lionel Trilling, and Alfred Kazin (most of Arendt’s letters are only available for viewing onsite at the Library of Congress, The New School University, or the University of Oldenburg).

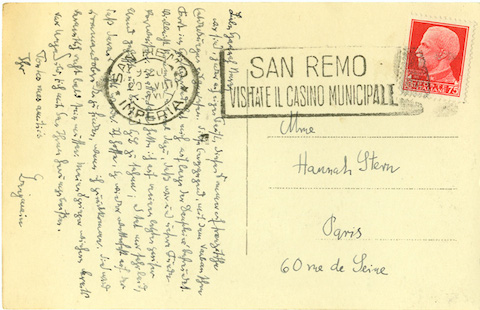

In addition to the “Arendt Marginalia” section, Bard hosts a gallery that includes “inscribed books, journals & manuscripts,” “artwork & photographs,” and “postcards and other correspondence” (such as the above postcard from Walter Benjamin, addressed to “Hannah Stern,” her married name at the time).

Lastly, for an excellent overview of Arendt’s life and work that puts all of the above materials in context, see the Library of Congress’s “Biographical Note” and be sure to read “Three Essays: The Role of Experience in Hannah Arendt’s Political Thought” by Jerome Kohn, director of the New School’s Hannah Arendt Center. As many know, Arendt, and many other German Jewish intellectuals who fled the Nazis, found a home at New York’s New School for Social Research (now New School University). And we have the New School (and an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant) to thank for the Library of Congress’s vast, digitized collection of Arendt’s papers, which preserves her legacy for generations to come.

Related Content:

Hannah Arendt Discusses Philosophy, Politics & Eichmann in Rare 1964 TV Interview

Hannah Arendt’s Original Articles on “the Banality of Evil” in the New Yorker Archive

The Trial of Adolf Eichmann at 50

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

She has already become legendary, almost mythic.

Thinking. It is our political obligation to think.