Has any political party in Western history had as vexed a relationship with art as the German National Socialists? We’ve long known, of course, that their uses of and opinions on art constituted the least of the Nazi party’s problems. Still, the artistic proclivities of Hitler and company compel us, perhaps because they seem to promise a window into the mindset that resulted in such ultimate inhumanity. We can learn about the Nazis from the art they liked, but we can learn just as much (or more) from the art they disliked — or even that which they suppressed outright.

Current events have brought these subjects back to mind; this week, according to The New York Times, “German authorities described how they discovered 1,400 or so works during a routine tax investigation, including ones by Matisse, Chagall, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso and a host of other masters,” most or all previously unknown or presumed lost amid all the flight from Nazi Germany. Hitler himself, more a fan of racially charged Utopian realism, wouldn’t have approved of most of these newly rediscovered paintings and drawings.

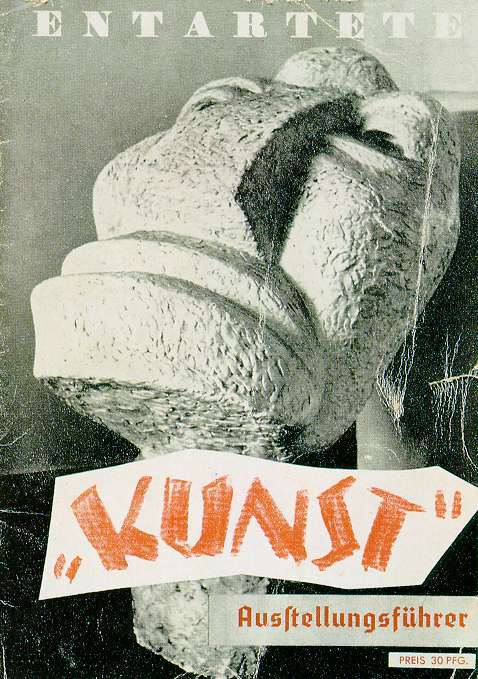

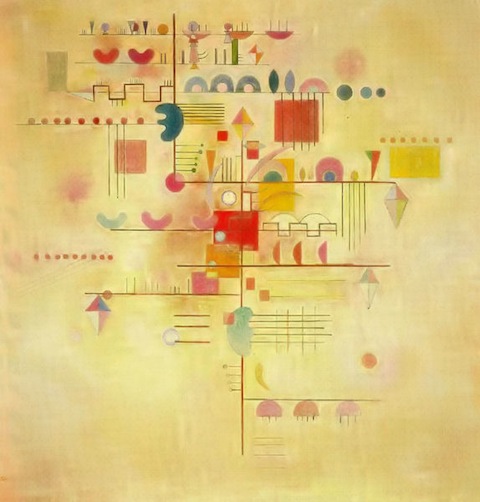

In fact, he may well have thrown them into 1937’s Degenerate Art Exhibition. Four years after it came to power,” writes the BBC’s Lucy Burns, “the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich. The Great German Art Exhibition [the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung] was designed to show works that Hitler approved of — depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealised soldiers and landscapes. The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art — modern, abstract, non-representational — or as the Nazis saw it, ‘degenerate.’ ” This Degenerate Art Exhibition (Die Ausstellung “Entartete Kunst”), the much more popular of the two, featured Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Wassily Kandinsky, Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and George Grosz. There the Nazis quarantined these confiscated abstract, expressionistic, and often Jewish works of art, those that, according to the Führer, “insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill” and “cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence.” And if that sounds rigid, you should see how that Nazis dealt with jazz.

Note: For more on this subject, you can watch the 1993 documentary Degenerate Art.

Related Content:

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

The Nazis’ 10 Control-Freak Rules for Jazz Performers: A Strange List from World War II

Joseph Stalin, a Lifelong Editor, Wielded a Big, Blue, Dangerous Pencil

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

According to that same Times article, the “Degenerate Art” exhibition — as the picture you provide with this article suggests — was, for the Nazis, an embarrassingly big hit. Not hard to imagine that the average Fritz in the street would prick up his ears when told he could see some real degenerate art up close. My guess is a lot of Germans who’d otherwise never have bothered visiting a museum of any kind stood patiently in line for this show.

And, funny enough, my browser does not display the images of this particular post?