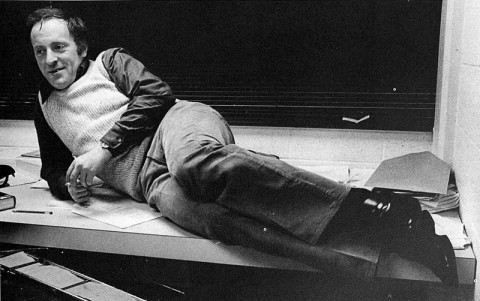

Image from the University of Michigan Yearbook, via Wikimedia Commons

Although Joseph Brodsky was one of the most celebrated Soviet dissidents of the 20th century, the Nobel Prize-winning poet had been unerringly hounded by the repressive Soviet government, which had labeled his poetry as “pornographic and anti-Soviet.” Refusing to abandon his writing, Brodsky was repeatedly brought to court, and once sentenced to 18 months of labor in the Arctic region of Arkhangelsk. During one of his courtroom appearances, the young poet displayed an admirable level of testicular fortitude when the judge asked him, “Who has recognized you as a poet? Who has enrolled you in the ranks of poets?” Brodsky, defiant, replied “No one. Who enrolled me in the ranks of the human race?”

In 1972, Brodsky left the USSR for America, where he was widely sought as a lecturer (his academic bedpost included notches from Cambridge, Columbia, the University of Massachusetts, and Mount Holyoke). On the heels of his winning the 1986 National Book Critics’ award for criticism for Less Than One and receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987 (pornographic writing, it seems, does quite well with the critics), Brodsky was invited to give the 1988 commencement address at the University of Michigan.

Brodsky’s remarks are far from the galvanizing dose of inspiration that many commencement addresses impart, and certainly not what Michigan graduates were expecting. Rather than uplift, the poet’s words soberly ground the audience; instead of wrapping them in a warm self-assuredness, the life tips are jarring, like an ice bath. Brodsky’s address is a mix of wry humour, acknowledgement of our absurdist existential dilemma, and bold, honest compassion. Reading Brodsky’s advice, one can’t help but feel that the poet valued his flawed humanity even more than his art; likely, they were inseparable.

Here’s a boiled-down version of the poet’s remarks:

1) “Treat your vocabulary the way you would your checking account.” Expression often lags behind experience, and one should learn to articulate what would otherwise get pent up psychologically. Learn to express yourself. Get a dictionary.

2) “Parents are too close a target… The range is such that you can’t miss.” Be generous with your family. Even if your convictions clash with theirs, don’t reject them—your skepticism of your infallibility can only benefit you. It will also save you a good deal of grief when they are gone.

3) “You ought to rely on your own home cooking.” Do not expect society to arrange itself to your benefit—there are too many people whose desires conflict for that to happen. Learn to rely on yourself, and help those who cannot.

4) “Try to not to stand out.” Do not covet money or fame for their own sake. It is best to be modest. There is comfort joining the ranks of those who follow their own discreet paths.

5) “A paralyzed will is no dainty for angels.” Do not indulge in victimhood. By blaming others, you undermine your determination to change your circumstances. When life confronts you with hardships, remember that they are no less an intrinsic part of existence. If you must struggle, do so with dignity.

6) “To be social is to be forgiving.” Do not let those who have hurt you live on in your complaints. Forget them.

The full text—irrevocably more pithy and eloquent—may be found here.

Related Content:

‘This Is Water’: Complete Audio of David Foster Wallace’s Kenyon Graduation Speech (2005)

George Saunders Extols the Virtues of Kindness in 2013 Speech to Syracuse University Grads

Neil Gaiman Gives Graduates 10 Essential Tips for Working in the Arts

You have used “irrevocably” incorrectly and “testicular fortitude” is a frankly ridiculous formulation.

The address was to students at the University of Michigan, not Massachusetts.

“unerringly hounded” ?

Drawing attention to Brodsky is worthwhile,and appreciated. The paraphrases of his quotes seem unnecessary- and several appear to be inaccurate.

Thanks for mentioning Brodsky and his address. I was one of the U‑M graduates in the audience that day and can’t help but recall how initially disappointed I was at the prospect of listening to a poet, rather than a U.S. president (that those graduating in May of ’89 would hear.) I was completely wrong.

I loved what he had to say at the time and often return to his words, sometimes in disappointment, when I ponder if I learned anything from his unassuming wisdom, after all. Thanks again.

Thanks again for mentioning it.